Carl Beam sought to distance himself from the Woodland School painting style developed by his Ojibwe contemporary Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007). Through his work in many different mediums, Beam highlights the significant harm that colonialism has had on the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (North America). His art treats a wide range of issues: the tragedy of the residential school system, alternative conceptions of time and space held by Indigenous peoples, different notions of fame and notoriety, and the harm caused by losing connection with the environment that sustains all life.

A New Approach to Indigenous Art

In the late 1970s, after Beam abandoned his graduate studies at the University of Alberta, he devoted himself fully to a career as an artist. At the time, there were very few contemporary artists of Indigenous descent (or from other minority groups) practising professionally in Canada. An exception was found on Manitoulin Island, where several young Ojibwe artists who rejected formal training and saw painting as a means of expressing their culture and traditional spiritual beliefs had formed a community. They called themselves the Woodland School. The founder and leading member was Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007). Other members included Blake Debassige (1956–2022), Joshim Kakegamic (1952–1993), Daphne Odjig (1919–2016), Carl Ray (1943–1978), and Roy Thomas (1949–2004). Their style, which referenced Anishinaabe spiritual teachings, was becoming increasingly popular with art critics and collectors, but it was radically different from what Beam was beginning to develop in his own practice.

In general, Woodland School art is characterized by colourful compositions with symbolic figures, animals, and spirits inhabiting mystical worlds and often shown in states of transformation. Morrisseau’s epic work Artist and Shaman between Two Worlds, 1980, is an iconic example of the subject matter, style, and themes associated with the Woodland School. Although Beam respected this approach, he saw its visual devices, which for the most part followed Morrisseau’s style, as curtailing his own and perhaps other artists’ creative intentions and inadvertently contributing to a limited understanding of what contemporary Indigenous art could be.

In the late 1970s, Beam began to combine found objects with painting, collage, prose, and poetry. This approach—on display in Contain that Force, 1978—placed him firmly in an emerging category of Indigenous artists whose works reflected a radically different creative sensibility. Robert Houle (b.1947), a Saulteaux painter and curator who also identified as part of this group, described it as a collection of artists who had “the distinction of having come from two different aesthetic traditions: North American and western European.” In addition to Houle, the group included Abraham Anghik Ruben (b.1951), Bob Boyer (1948–2004), Domingo Cisneros (b.1942), Douglas Coffin (b.1946), Larry Emerson (1947–2017), Phyllis Fife (b.1948), Harry Fonseca (1946–2006), George C. Longfish (b.1942), Leonard Paul (b.1953), Edward Poitras (b.1953), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (b.1940), Randy Lee White (b.1951), and Dana Alan Williams (b.1953).

-

Robert Houle, Kanata, 1992

Acrylic and conte crayon on canvas, 228.7 x 732 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

-

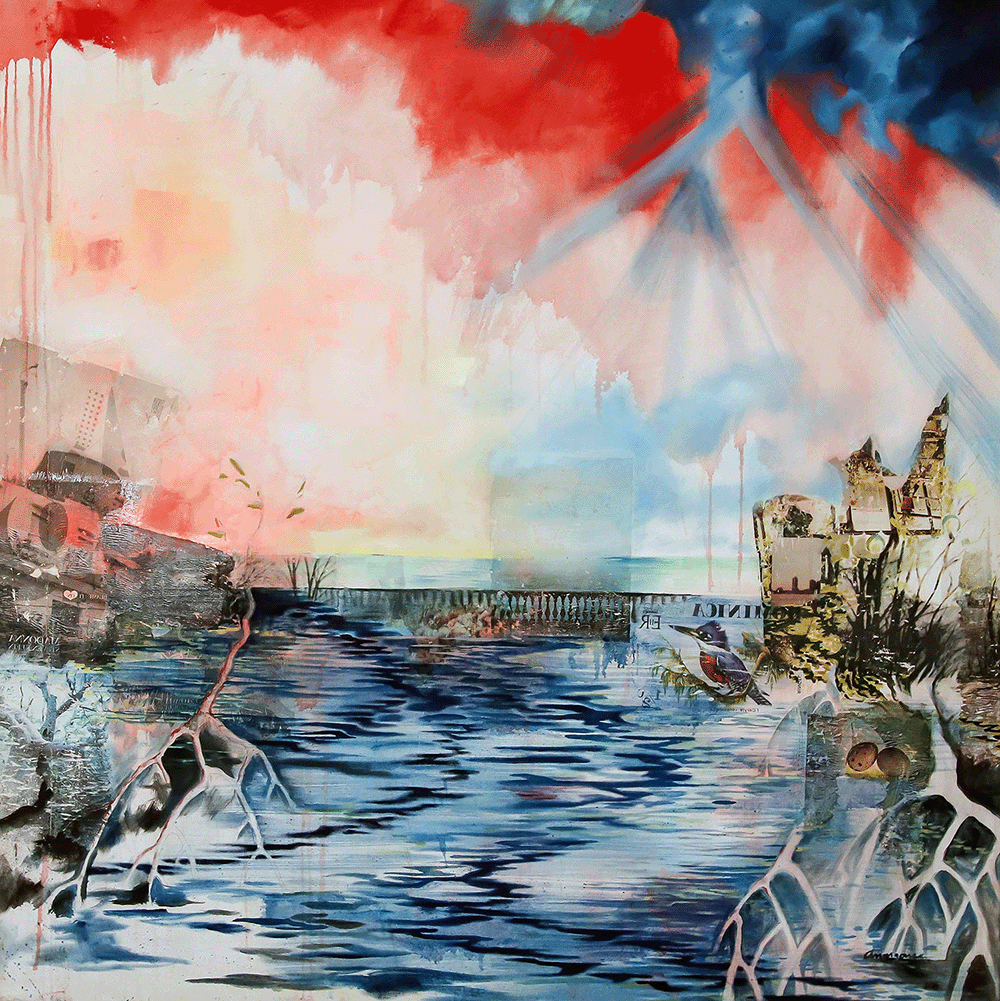

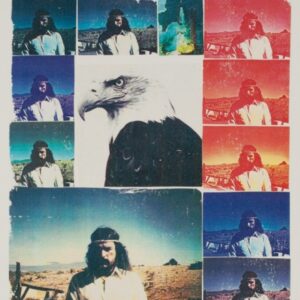

George Longfish, America: 500 Years, “I” is for Indian as “I” is for Invisible #2, 1992

Coloured pencil, photograph, graphite, stamps, and reflective mylar on board, 49.8 x 76.2 cm

Washington State Arts Commission, Olympia

-

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Blackwater Draw II, 1983

Acrylic and fabric on canvas, 121.9 x 91.4 cm

John and Susan Horseman Collection

-

Bob Boyer, Grandfather Will Come Again, 1987

Oil, acrylic, chalk pastel, charcoal on blanket, 192 x 231.4 cm

The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern, Saskatoon

In challenging the influence of the Woodland School, Houle sought to defy the underlying assumption that First Nations artists needed to be categorized at all. Houle’s own work, such as Kanata, 1992, reframes the idea of what constitutes a “history” painting, subverting supposedly heroic depictions of colonial conquest that subjugated First Nations peoples. Bob Boyer’s painted blankets, such as Grandfather Will Come Again, 1987, address the issue of First Nations genocide. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith‘s abstract landscapes, including Blackwater Draw II, 1983, with their pictographic symbolism in conversation with Abstract Expressionist–inspired colour fields, treat the theme of the alienation of the American Indian in the modern world. All the above-mentioned artists blended tradition with contemporary idioms, themes, media, and modes to develop personal art forms of engaged political and cultural advocacy that challenge racist stereotypes of what constitutes Indigenous art. They also sought to highlight the oppressive social conditions that impoverish contemporary First Nations peoples across Turtle Island.

Beam was at the vanguard of this groundbreaking approach to Indigenous art. His interest lay in experimenting with and adapting current styles and techniques. Through his complex, semiotically informed layering of imagery and signs, collaging, and startling visual juxtapositions, as well as his innovative use of performance-based practice, he challenged colonial power, exclusionary and distorted historical narratives, racist paradigms, limited conceptions of nationalism, and narrow definitions of what constituted First Nations art.

Above all, he was an advocate for artistic agency unconstrained by limiting categories based on race. His work quickly struck a chord with his fellow Indigenous artists, as well as with curators across the country. In the catalogue accompanying his solo exhibition at the Thunder Bay National Exhibition Centre and Centre for Indian Art (now the Thunder Bay Art Gallery) in 1984, curator Elizabeth McLuhan wrote, “His message is urgent and inescapable.… Beam transforms his personal voice into a global conscience.”

A Groundbreaking Acquisition

Throughout his career, Beam advocated for changes in the way cultural institutions supported (or failed to support) contemporary Indigenous art—which was frequently referred to pejoratively as “Indian Art.” Works by Indigenous creators began entering national collecting institutions in the 1920s as “artifacts.” Most of these early acquisitions were cultural objects seized from potlatch ceremonies, which were banned through an amendment to the Indian Act in 1884. For more than a century, these works were regarded solely as anthropological or ethnographic specimens. By the early 1980s, the National Gallery of Canada had only a small collection of First Nations artifacts and a handful of prints and sculptures produced by Inuit artists. Beam’s ambition—stated at the third National Native Indian Artists Symposium in 1983—was to be the first openly Indigenous artist to have works exhibited and purchased by the National Gallery of Canada.

This distinction—the first openly Indigenous artist—was important for Beam because the National Gallery of Canada had purchased works by other First Nations artists, including Rita Letendre (1928–2021) and Robert Markle (1936–1990), but they were quietly doing their work without drawing attention to their backgrounds. If you wanted to participate equally in the modern art landscape, you had to conceal the fact that you were Indigenous. Some people did that. But Beam refused. He had the warriorship to demand that people accept he was an Indigenous artist with contemporary concerns.

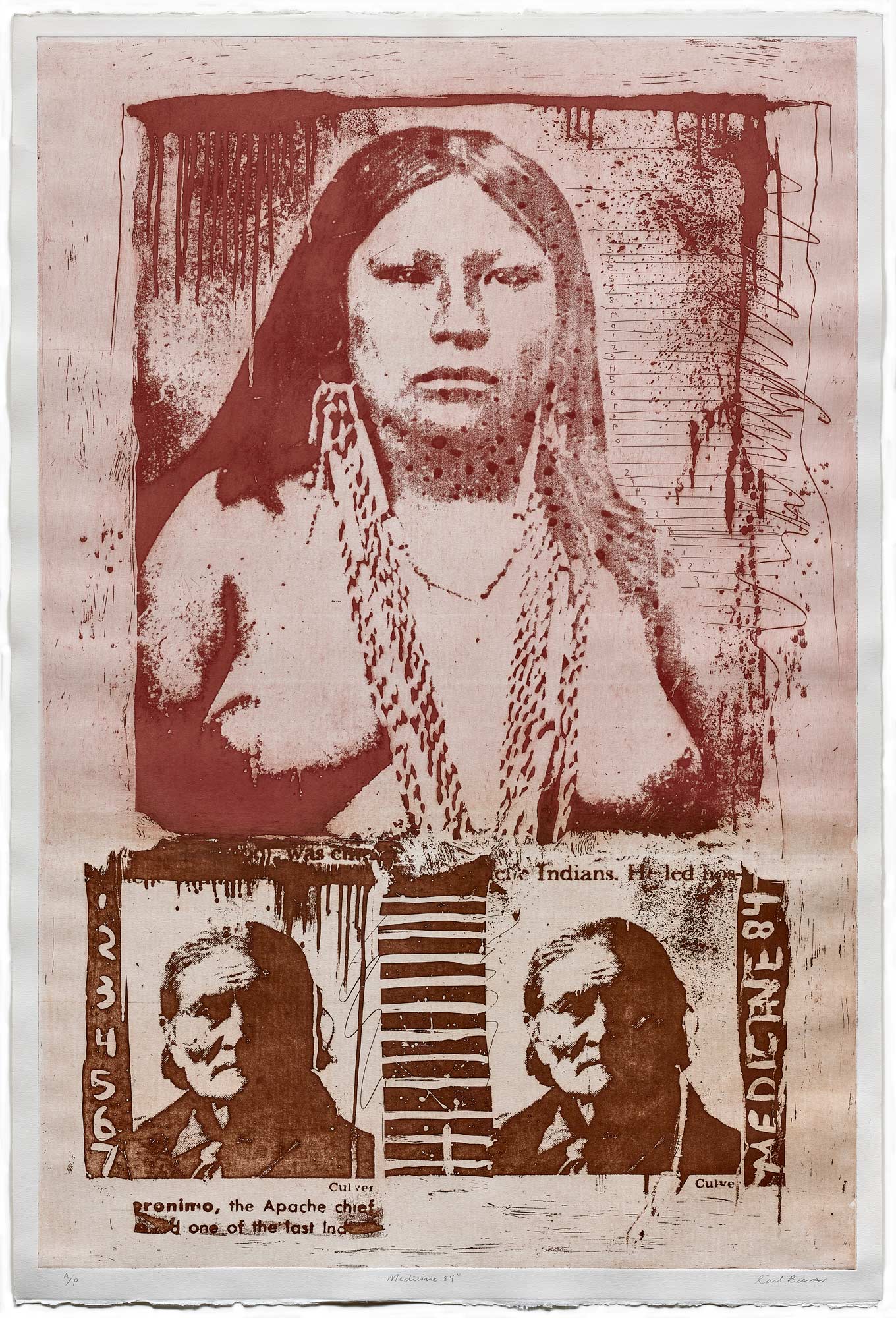

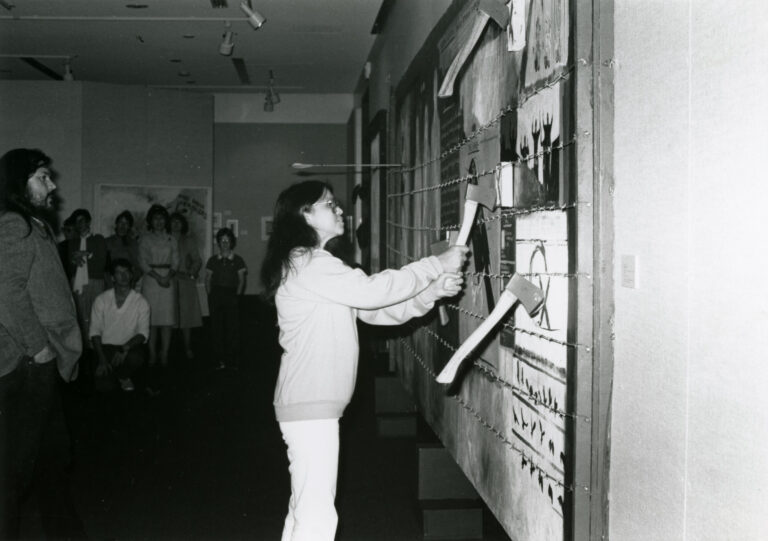

Spurred on by reactions to his art that ranged from quizzical to aggressively hostile, Beam produced pieces that rejected the public’s expectations of Indigenous artists. Through rigorous, visually dense, and monumental works such as Exorcism, 1984, he took aim at the art world’s established norms. When Exorcism was exhibited at the Thunder Bay National Exhibition Centre and Centre for Indian Art (now the Thunder Bay Art Gallery) in 1984, Beam encouraged viewers to become participants in the work by throwing a hatchet at it. Thumbing his nose at the taste-making establishment, which had failed to appreciate or embrace the validity of his expression as a visual artist, became a central theme in many of his paintings and prints.

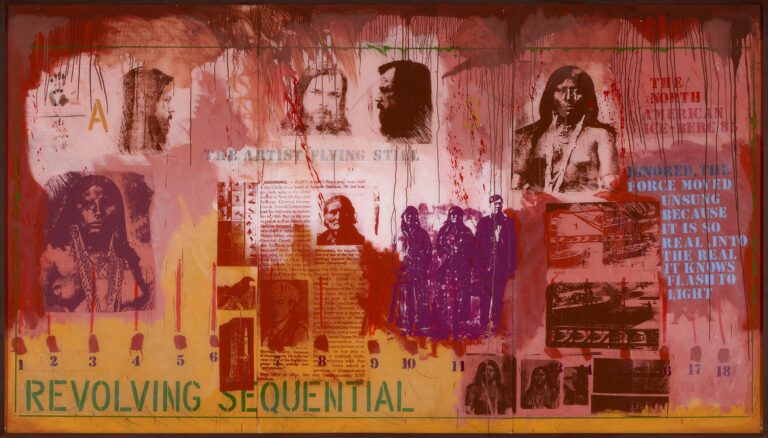

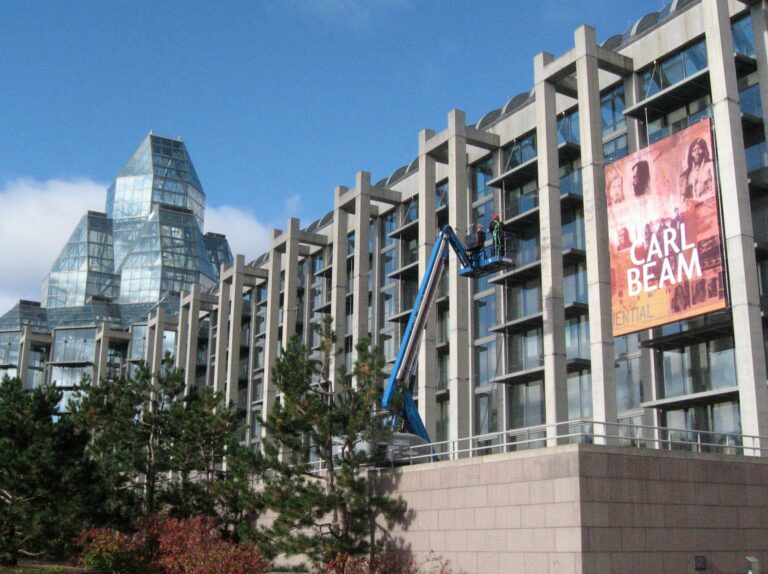

Despite this uneasy relationship, in 1986, the National Gallery of Canada acquired The North American Iceberg, 1985. Beam recounted that the gallery drove a hard bargain, and the work was sold for $16,000—just over a quarter of the $60,000 asking price. Nevertheless, this was the first time that an object of contemporary art by a self-identifying Indigenous artist was bought for the gallery’s contemporary collection.

Beam later decried the purchase, calling it a political act by the National Gallery, which, he said, had acquired a work by “Carl the Indian” and not “Carl the artist.” He felt used, saying:

I feel like a real dupe. At the time, I felt honoured, but now I know I was used politically. Native artists, as art-making citizens of Canada, put a lot of pressure on the National Gallery. Our argument was that someone like Norval Morrisseau doesn’t make artifacts that belong in an ethnological museum, he’s an important Canadian painter. So they bought a work by a native artist—me—as a way to hush us up, and at the time it succeeded. They bought four or five more only after realizing it was worse to have one native artwork than none. I can document it. They now have a dozen native artists in their collection, but there hasn’t been much good faith.

Indeed, few purchases were to follow Beam’s. By 1990, only six Indigenous artists were included in a field of 780 Canadian art acquisitions. Nonetheless, the purchase of The North American Iceberg remains a watershed moment in Canadian art history, and the start of a more equitable relationship between the art establishment and Indigenous creators.

Challenging Western Knowledge Systems

Time-distancing is the model used to displace native people from contemporary reality by making us into museum pieces. It is at the crux of a lot of problems. If Indian people can be made to inhabit an inauthentic time, to seem not to belong in the present and to be living outside our time, then it is easy to believe we have no real title to our land in the present reality. But I know that I live at the same time as anybody else, that I’m not something left over from the Stone Age. So, in my paintings I show that we’re all living in a cyclical time, with things fading in and fading out. I put the contemporary in a box and give it some distance.

—Carl Beam, 1990

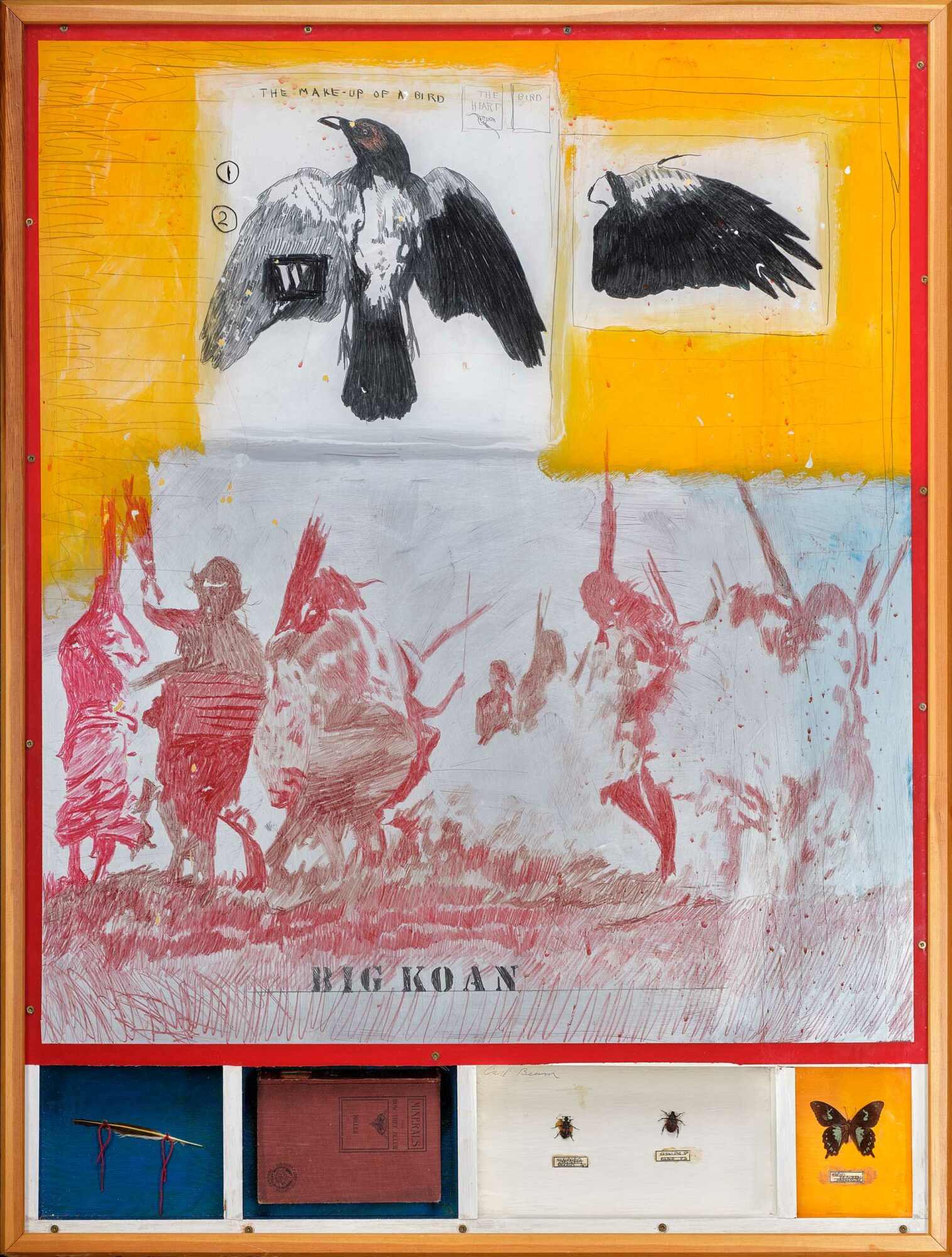

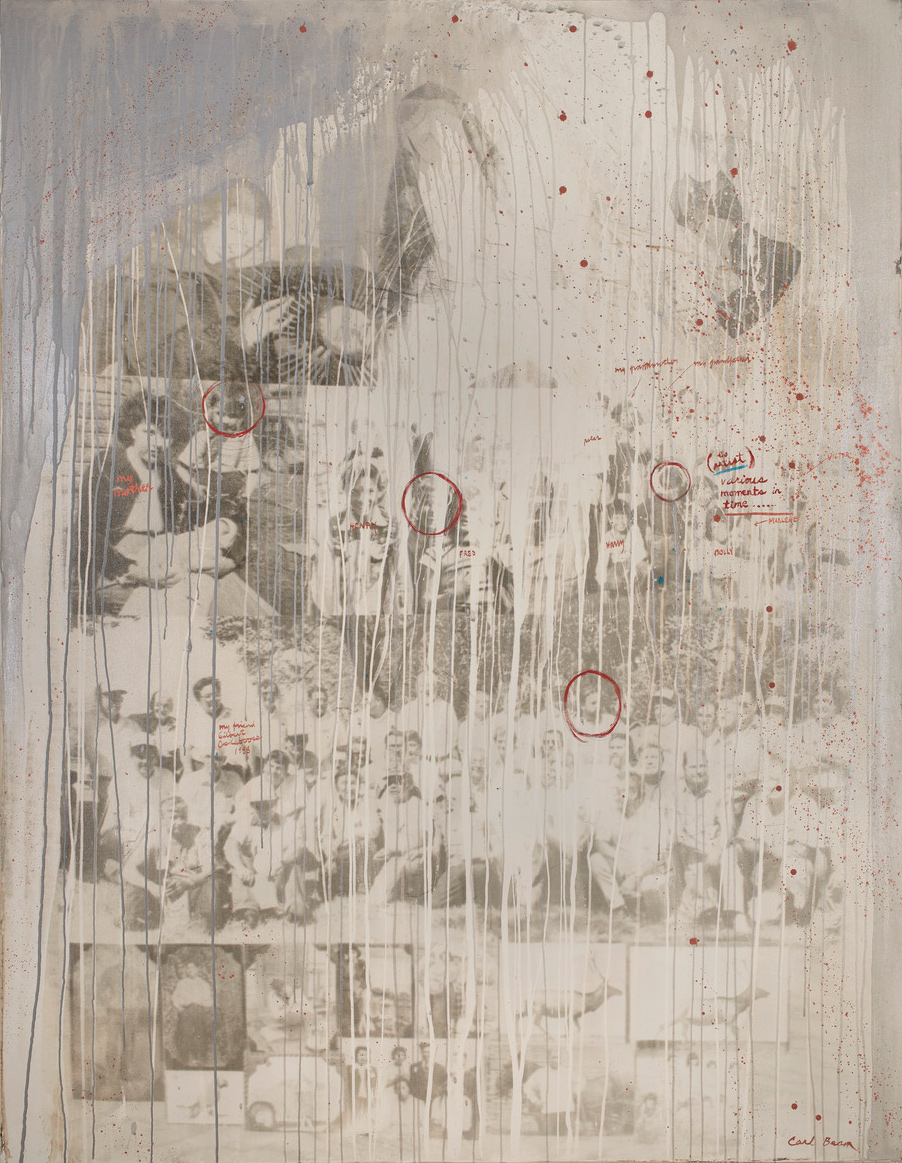

Time—how it is perceived, lived, and used as a colonizing tool—is a core element of Beam’s work. Embracing contemporary Pop art modes, he refused to be boxed in. Through collages like Big Koan, 1989, Beam juxtaposes objects, texts, and pictures from different times, giving viewers a visual portal through which they could travel between historical periods, time zones, and imaginative worlds.

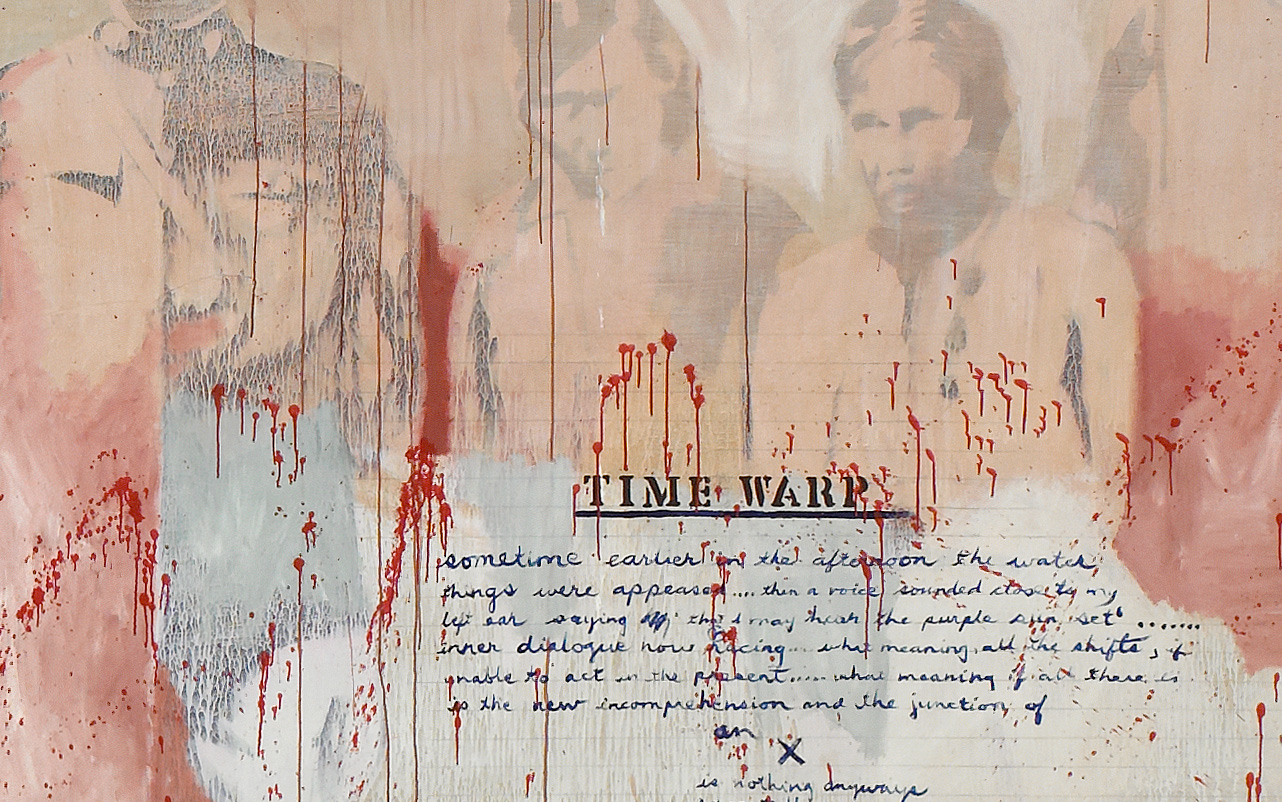

Beam felt limited by Western European–based rationalism and its linear sense of time. His engagement with the idea that time is cyclical—tied to recurring phenomena, such as habits that are shaped by seasonal change—informed his critique of Western systems of thought and the impacts of colonialism on Indigenous ways of knowing. In monumental works such as Time Warp, 1984, he resists linearity by juxtaposing images and texts that enfold past, present, and future onto a single canvas, acting, as curator Greg A. Hill writes, “as a permeable plane allowing the viewer to approach it and conceptually enter it at various points.” Measuring 3 by 12.2 metres, Time Warp was Beam’s largest work to this date.

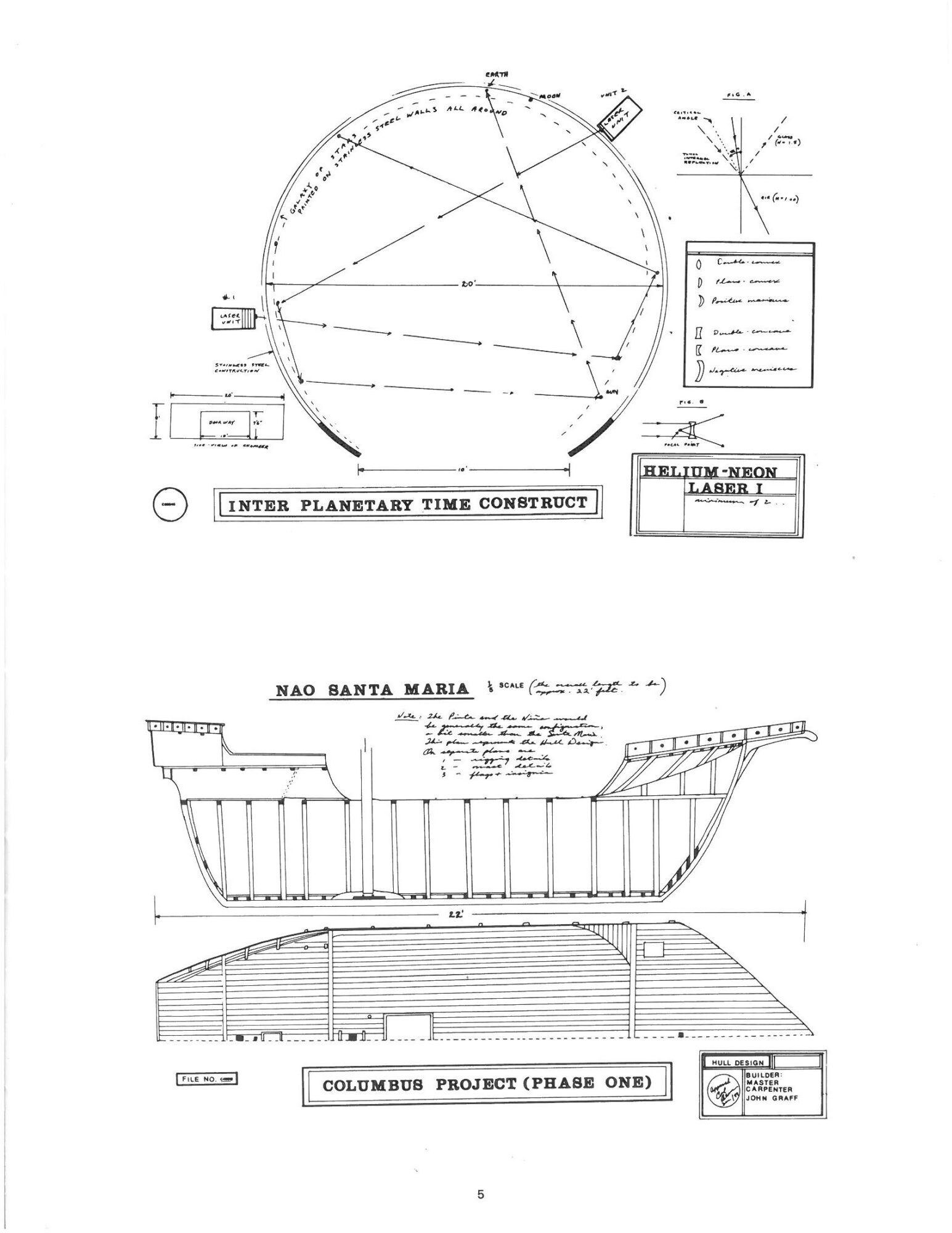

In 1988, on the eve of the quincentennial of Columbus’s arrival on Turtle Island and in the aftermath of the reunion held at Garnier High School, Beam took his critique of Western knowledge systems a step further by investigating the tragic effects of colonialism on the continent’s Indigenous nations, a subject he would revisit throughout his career. This investigation led to The Columbus Project, 1988–92, a four-year enterprise executed in several media, including painting, photo emulsion on canvas, and large-format etchings.

Whereas Time Warp challenges concepts of time, The Columbus Project takes aim at the notion of “discovery” and its impact on the ways histories are written—often by denigrating Indigenous knowledge and belief systems that predate European contact. With The Columbus Project, Beam wanted to raise the idea “that the moment of contact between the old and new worlds could no longer be celebrated as a triumphant moment of discovery,” but was instead the prelude to centuries of genocide and cultural annihilation of Indigenous populations in the Americas. Beam drew a straight line, for example, between rationalism and the sexual and cultural abuses that he and others suffered at residential schools because of destructive government policies.

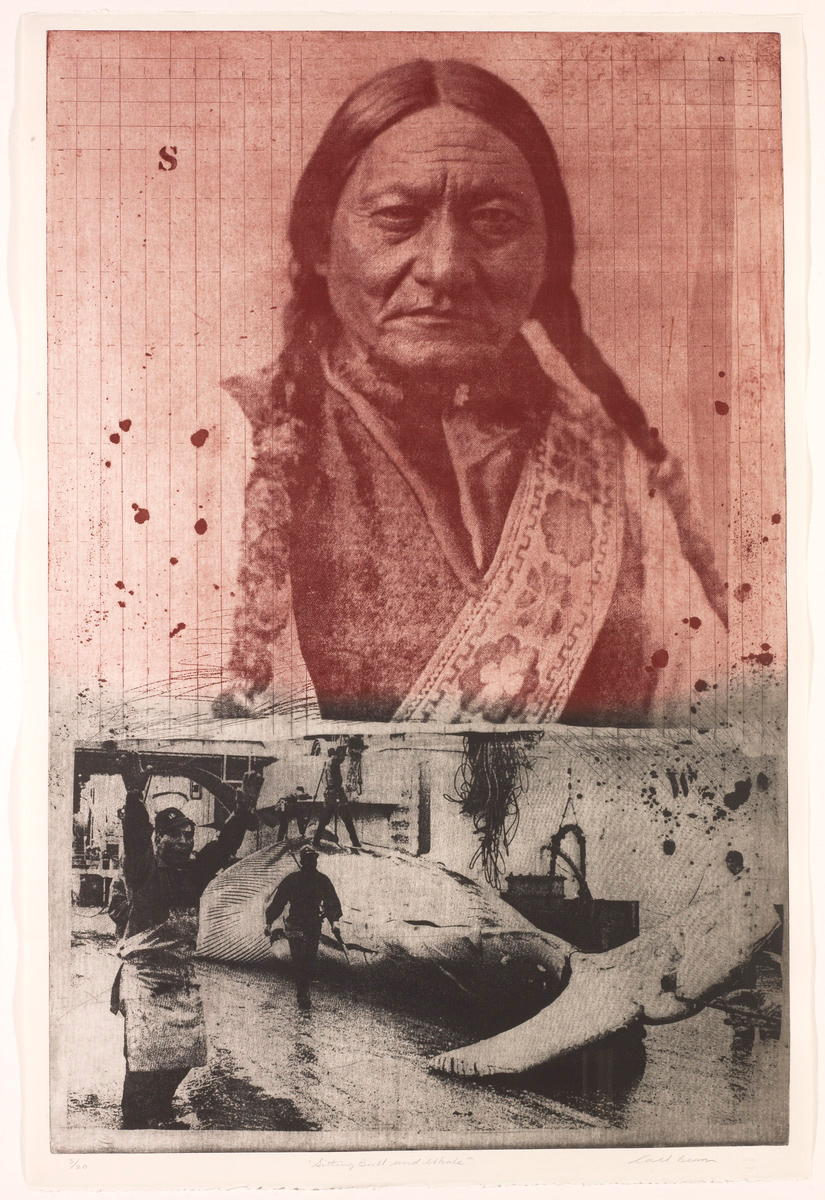

Like Time Warp, The Columbus Project juxtaposes seemingly disparate images in often radical matchups, as in Sitting Bull and Whale (from The Columbus Suite), 1990. Beam’s strategy was to create an image field of various signs that cannot simply be read in rational ways. Instead, he asks his viewers to validate all the associations that come into play while “reading” his work. Beam expresses his contempt for instruments of colonial domination by imploring viewers to derive their own meaning from his works, making space for a variety of thought systems and time-based experiences to coexist.

Ecological Concerns

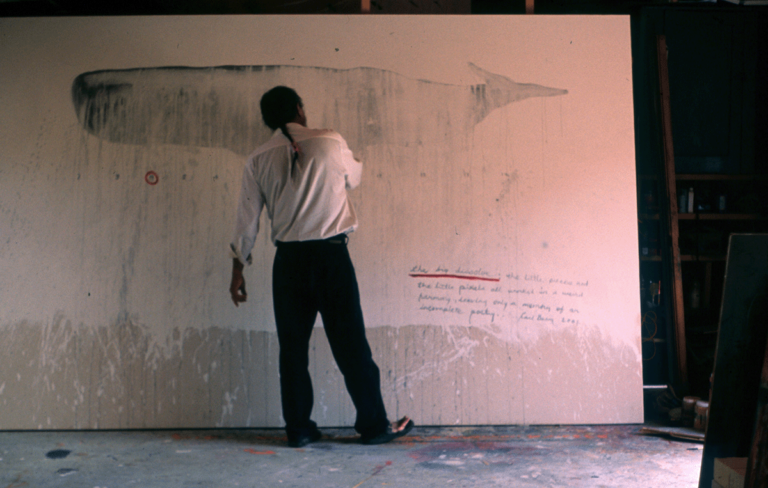

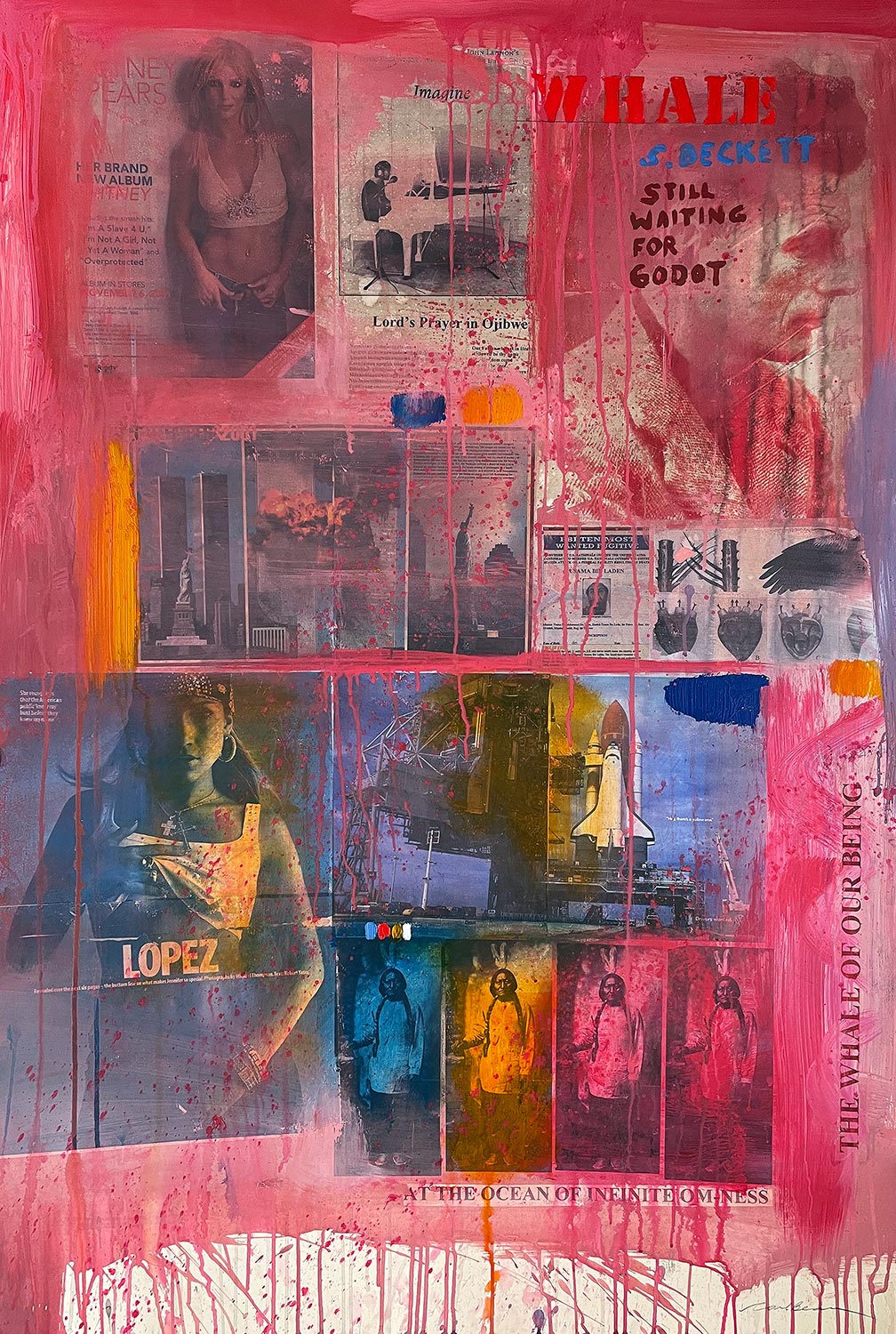

Beam embraced his role as social critic on topics that ranged beyond Indigenous issues like the struggle for self-representation, the effects of colonialism, the privileging of Western systems of knowledge, and the tragedy of the residential school system. He was also passionate about the environment and critical of the way environmentalists of the time seemed to view themselves as outside of shared nature, causally or experientially. In works from series such as The Whale of Our Being, 2001–03, he was interested in investigating the interconnectedness of worldly events as extensions of what he called “microscopic ecologies.”

Furthermore, he did not distinguish between micro and macro; an environment, he insisted, was not “out there,” divorced even from the ecologies that constitute a person’s microbiology or from the body politic of a community or nation. His environment was holistic, embracing the here, the past, and the future. The entirety of creation held a sanctity for Beam that he honoured both as a human being and as an artist. His concern embraced the pine forests as well as the great whales. He saw in the plight of the whale a metaphor for the fragile interconnectedness of the human and non-human worlds, or as he put it, “what happens to the whale happens to us.” Fostering a sustainable environment was, for Beam, an act of faith that required action. He spoke out against the use of chemicals that he saw as disproportionally and adversely affecting the poor and minorities, and negatively impacting the natural ecosystem. And he asked everyone who sought environmental protection and ecological sustainability to act in a manner that advanced positive change for all.

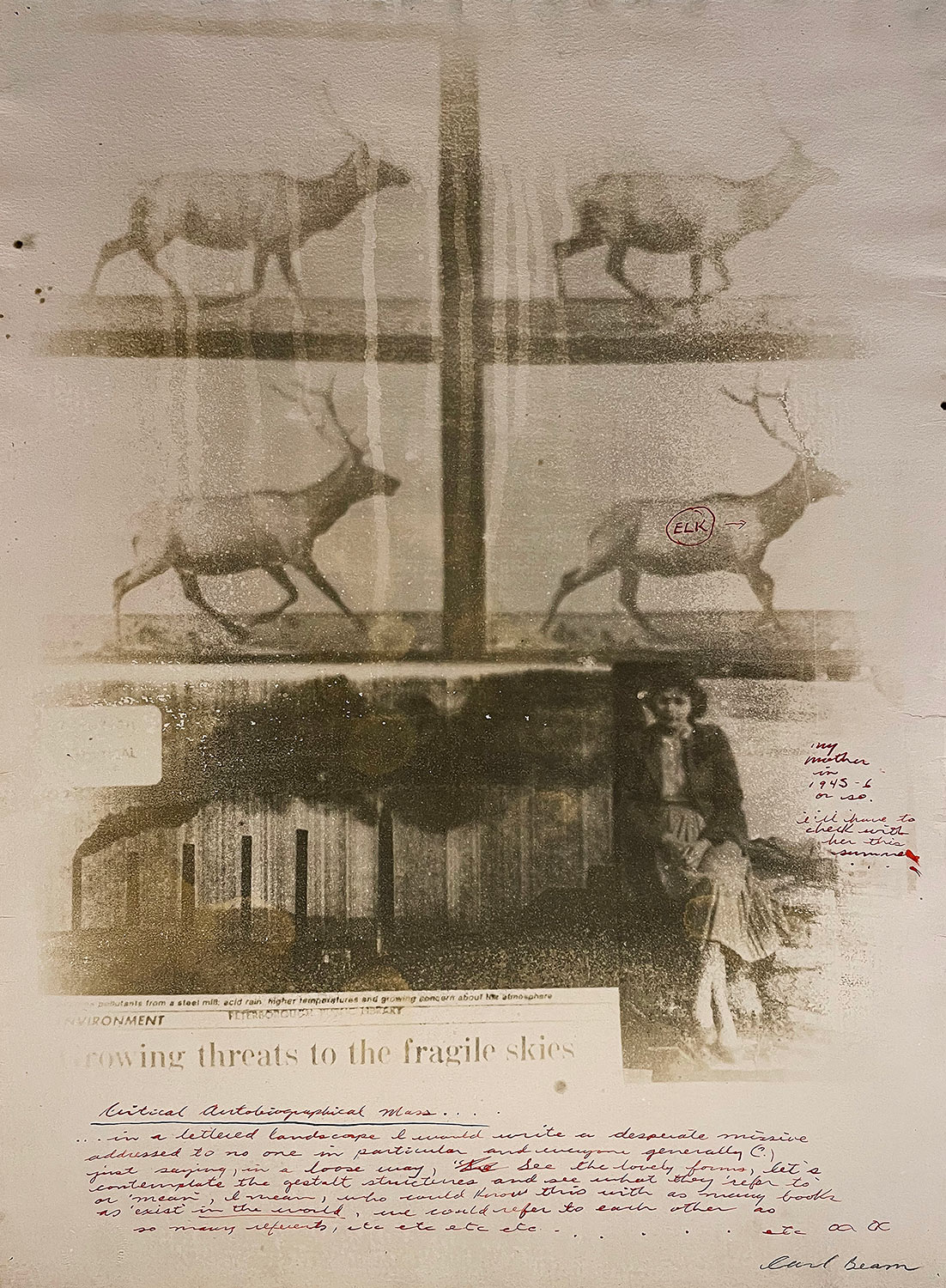

Beam’s art is infused with image fields that include photographs of men in hazmat suits with the text “Growing threats to the fragile skies” (Critical Autobiographical Mass, n.d.); newspaper clippings about dioxin alongside mechanical photos by Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) of running elk (Critical Autobiographical Mass); and images of Hiroshima and other disasters of war (Columbus Chronicles, 1992). By juxtaposing images of ecological disasters, Beam points his finger at their human causes. He believed the separation of human-based ecology from nature was a result of hubris—thinking that human knowledge and control are supreme, that the natural world is apart from us and, therefore, rightfully subjugated to our desires.

He was also openly critical of commodity-driven consumer society. His treatment of commodification—an ecology all its own—carried over into a series of prints and paintings examining the cult of celebrity. Consumption of the individual built on a foundation of superficial fashion and empty imaging is the theme of his Crossroads series, 2003–05, which includes an array of portraits of well-known figures from Albert Einstein and James Joyce to Cindy Crawford and Jennifer Lopez. At its centre is a moral question: What is the value of talent—creative, artistic, musical—when it is traded for worldly gain? Never shy about tackling difficult issues, Beam addresses planetary concerns head-on in his work.

Legacy and Reception

My work is only my own personal record of going through time. A sequence of events I had to live…so you could look at this.

—Carl Beam, 1980

Beam’s life and art were propelled by an omnivorous, urgent quest for knowledge, reflecting his impatience to move the world towards change. In his paintings, prints, and performance works, he tackled contemporary and historical themes that he felt had not been previously explored in artistic terms, making it possible for Indigenous creators to be recognized as contemporary artists in national dialogues.

Beam believed that being an artist made it morally imperative for him and his viewers to interact with and deconstruct national myths. He felt a great responsibility to shed light on the parts that were tattered and in need of repair, to delete others, and to add mythologies when necessary. To this end, Beam was essential in starting the dialogue on residential schools in Canada, in initiating the national apology to survivors, and in moving the separate nations towards an eventual reconciliation. An entire generation grew up seeing his works in art galleries across the country and, in so doing, became more outspoken on racism and inequality. It is for this reason that Beam’s Burying the Ruler, 1992, was chosen to be the central image on the cover of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015.

Although his art demands considered observation, a remarkable aspect of the work is that it invites the viewer to discover the shape of meaning, knowledge, time, and history. Collage works such as Time Dissolve, c.1992, force audiences to look through a non-linear lens to decipher the significance of their signs and symbols. Beam held up his compositions as emblems of an alternative way to acquire and express knowledge—one gained through an intensely personal visual interaction. This unique approach to making art gives non-Indigenous people ways to interact with stories of unfairness, atrocity, ecological collapse, genocide, and the failures of colonialism without feeling blamed, shamed, guilted, or otherwise judged. This is an incredible feat. To be able to engage with the histories as Beam conceived them is even now fraught with sensitivities. But Beam waded into them heart first, like a warrior. And in embracing art’s ability to enact social change, by arming himself with intellect and literature, he battled.

Now, more than a decade after his passing, there is an expanded generation of Indigenous artists who have not had to fight against expectations that their work would be in the manner of the Woodland School. But a second hurdle—which Beam found vexing to his last—remains: the systematic limitations we place on how Indigenous art functions in this country. Until Indigenous artists can be a part of the fabric of the national art community without having to shoulder the burden of explaining or satirizing their own and mainstream Canadian culture, his legacy is not fully realized.

I’m grateful to my father for so, so many things, including the fact that he chose to keep me close to him, and that he educated me in the way he did art, colour, and paint. Art is the great love of my life, and my father paved the way for me to be able to fully exercise my autonomy as an artistic thinking person in Canada. I get to paint whatever I want. I can create work in any media and call it my art, and people understand that it is. Nobody has ever told me, “No, Anong, you can’t paint that way.” I owe that to him.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements