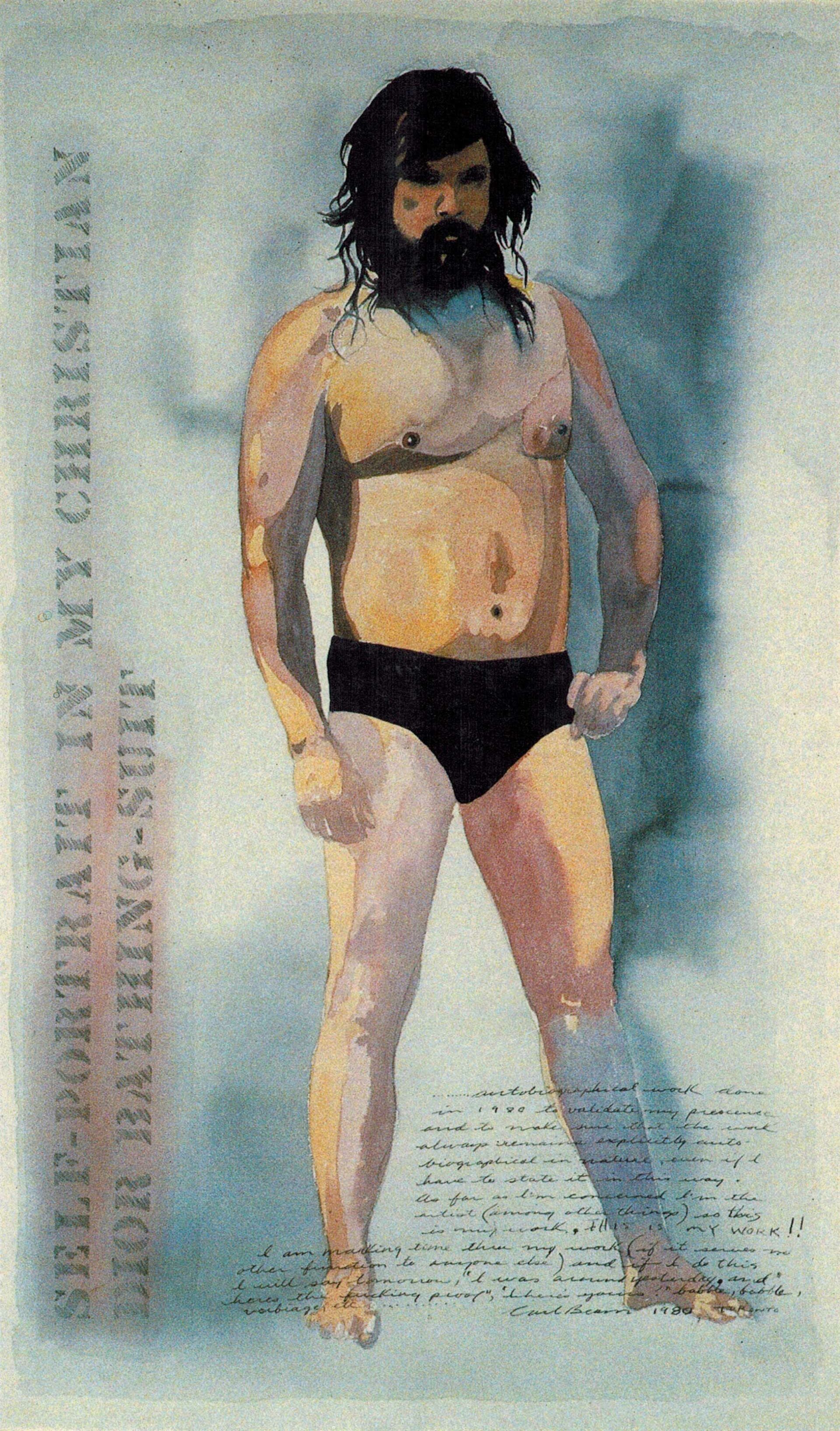

Self-Portrait in My Christian Dior Bathing Suit 1980

Carl Beam, Self-Portrait in My Christian Dior Bathing Suit, 1980

Watercolour on paper, 106 x 65.5 cm

Private collection

© Estate of Carl and Ann Beam / CARCC Ottawa 2024

In this iconic self-portrait, Carl Beam depicts himself, clad only in a black bathing suit, in a confrontational manner—upending the viewer’s expectations for how an Indigenous man should comport himself. With a hand on his hip and his hair hanging loose and long, he gazes from beyond the picture plane, his eyes ablaze with an eagle-like intensity. The title makes a clear reference to the fact that his bathing suit was purchased from an elegant high-fashion brand. But instead of positioning himself as an idealized pin-up, Beam presents himself as a creative subject in control of his own image.

Like much of his large-scale work, the portrait includes lines of stream-of-consciousness text written in Beam’s own hand:

…autobiographical work done in 1980 to validate my presence and to make sure that the work always remains explicitly auto-biographical in nature, even if I have to state it in this way. As far as I’m concerned, I’m the artist (among other things) so this is my work. THIS IS MY WORK!!

I am marking time through my work (if it serves no other function to anyone else) and if I do this I will say tomorrow, “I was around yesterday, and here’s the fucking proof, where’s yours?” babble, babble, verbiage, etc….

—Carl Beam, 1980, Toronto

With this defiant image, Beam confronts issues of self-representation. He undermines, as curator Richard William Hill has argued, not only the suppositions of the art audience of the early 1980s, “which would have expected Anishinaabe artists to be working in the so-called Woodland School style,” but also widely held assumptions that Indigenous men did not own designer clothing. Beam addresses both beliefs head-on while simultaneously pointing out how absurd they were: “There he [was,] standing in his Christian Dior bathing suit. Native people at that time weren’t really allowed to have Christian Dior bathing suits.… That’s one of the funny things. We weren’t considered to exist in modern times, especially in our prosperous modern time where we might want to have a Christian Dior bathing suit.” By depicting himself in this manner, Beam combats—in a very tongue-in-cheek way—the centuries-long treatment of Indigenous subjects in art as ethnographic or anthropological artifacts, and he undermines stereotypes that originated in paintings by Paul Kane (1810–1871) and Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1872).

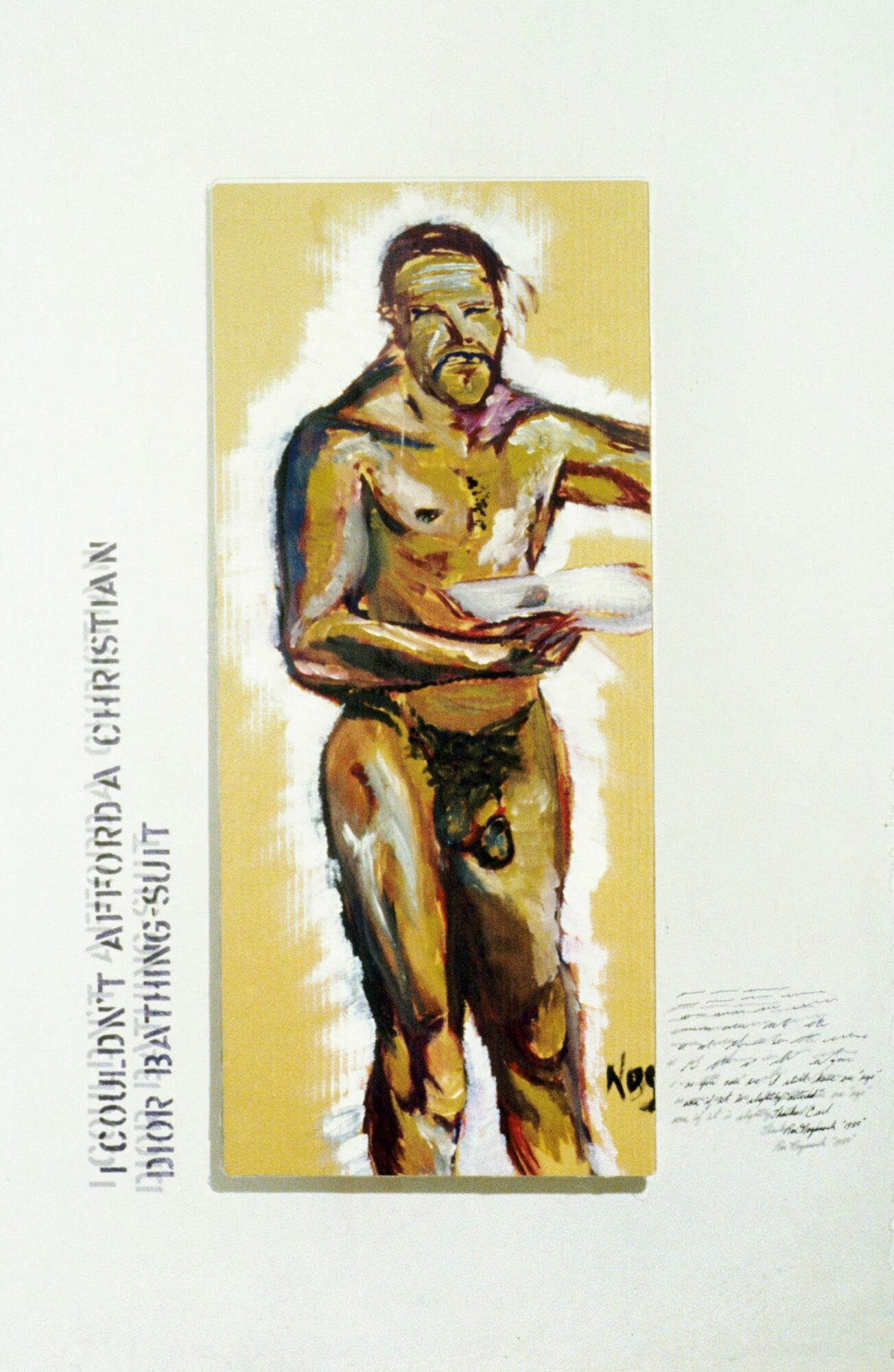

The portrait elicited a range of responses when it was shown in 1984 as part of Beam’s major solo exhibition, Altered Egos: The Multimedia Work of Carl Beam, at the Thunder Bay National Exhibition Centre and Centre for Indian Art (now the Thunder Bay Art Gallery). Artists Ron Noganosh (1949–2017) and Viviane Gray (b.1947), for instance, reacted with their own works, titled I Couldn’t Afford a Christian Dior Bathing Suit, 1990, and Carl, I Can’t Fit into My Christian Dehors Bathing Suit!, 1989. Assessing the critical reception to Beam’s portrait, scholar Allan J. Ryan noted that while the painting was deeply subjective—“a fierce affirmation of self-worth and personal experience”—it helped more broadly redefine the parameters of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada by “[speaking] passionately of the need for other [Indigenous] artists to create their own images of lived experience.” This work, which Beam himself claimed “was whipped off in an afternoon,” has endured as a challenge to anyone who would try to confine self-representation to narrow or racist categories.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements