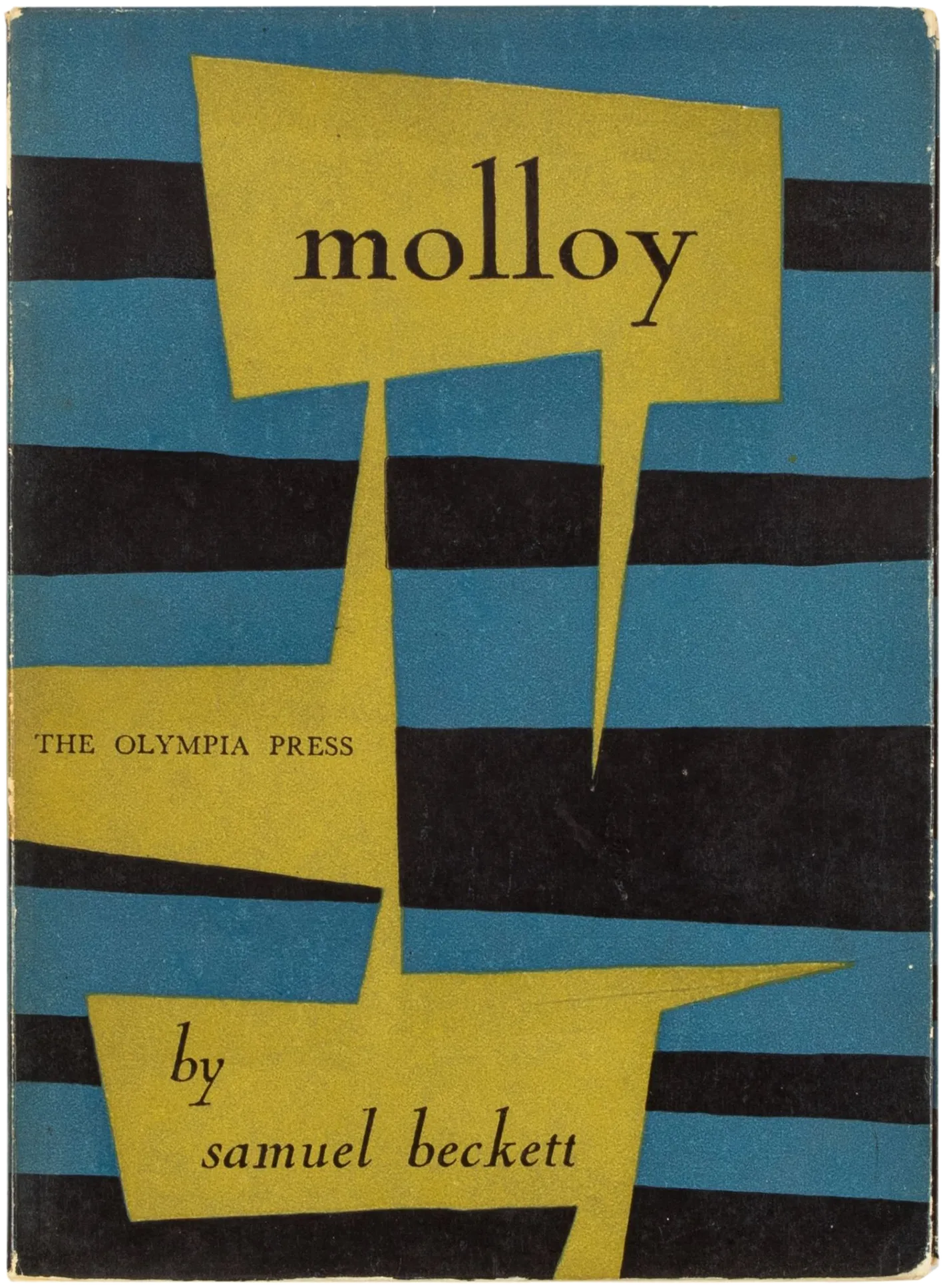

Betty Goodwin’s artistic career had a slow start, without the rigours of formal fine-art instruction. But being self-taught may have contributed to the openness with which she experimented with materials, techniques, and media. Her artistic influences ranged from the work of Bruce Nauman (b.1941) and Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) to the writings of Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) and Primo Levi (1919–1987). Unbound by format or the constraints of a single medium, Goodwin used found objects, text, and photographs. With methods she developed painstakingly through trial and error, she created the unique visual vocabulary that defined her work.

An Appetite for Experimentation

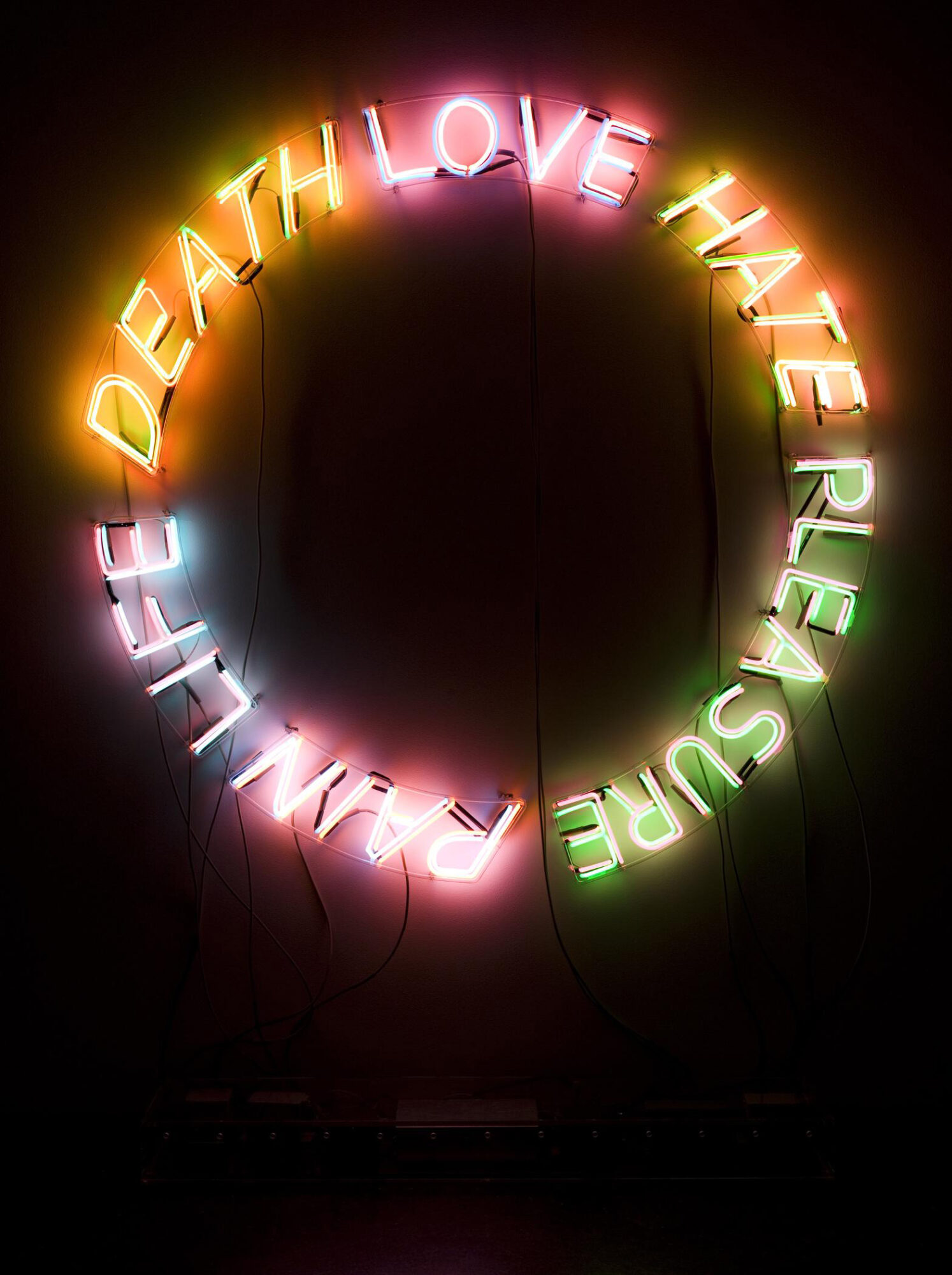

In notes she made in the early 1990s for a presentation on the development of her work, Goodwin scribbled names of artists who interested her. The range reveals her enduring attraction to specific themes and materials rather than media or styles. Among those she named were painters Philip Guston (1913–1980), who turned away from abstraction to make personal works reflecting the social and political upheavals of the late 1960s; Max Beckmann (1884–1950), long admired by her and whose increasingly brutal imagery expressed the rise of Nazism in the 1930s; and Mario Merz (1925–2003), whose work in several media conjured the innate energy of organic and inorganic matter. The variety of material means and range of strong emotions elicited by Bruce Nauman’s (b.1941) art was also an inspiration. His work features in Goodwin’s collections of snapshots taken when travelling and years later, in 2000, when she had become immersed in daily news of atrocities around the world. She identified with Nauman’s position and quoted him in her notebook. He said: “My work comes out of being frustrated with the human condition. And about how people refuse to understand other people. And about how people can be cruel to each other.”

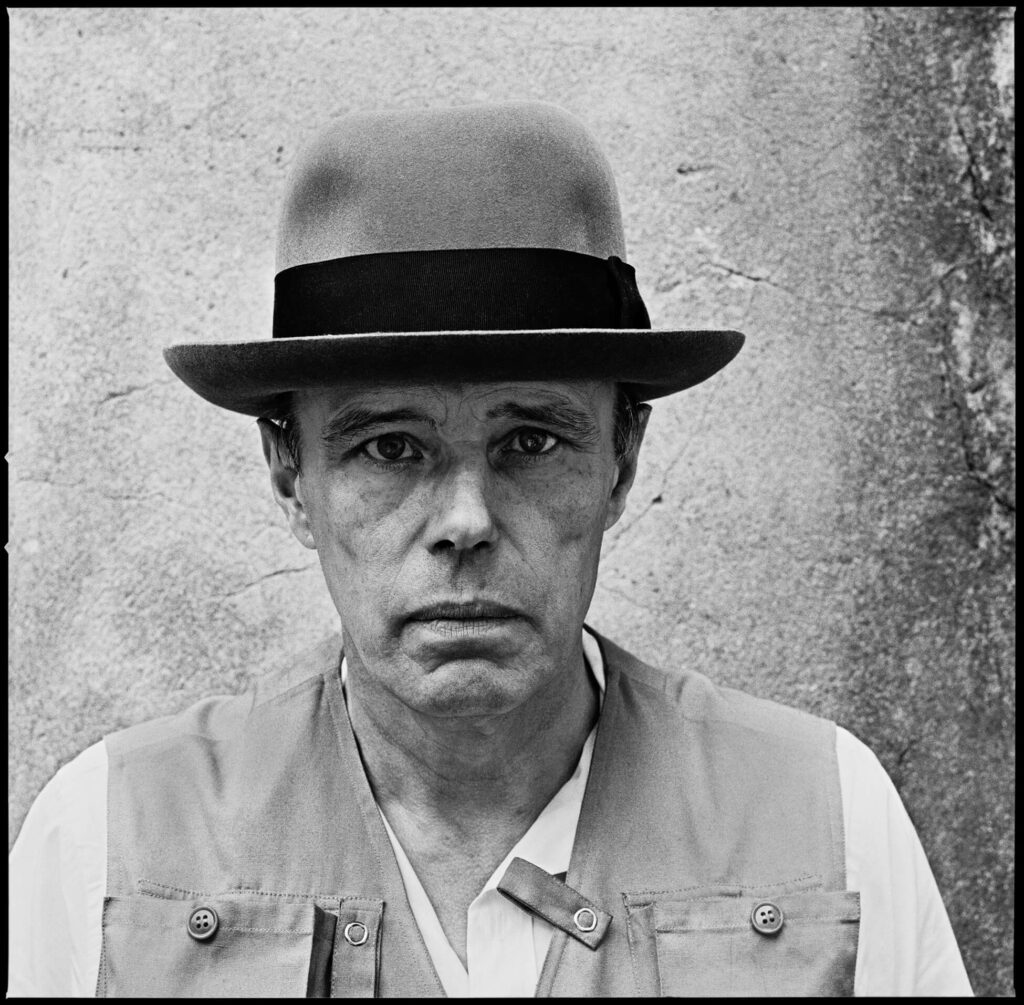

However, Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) was always at the top of Goodwin’s list of artists of interest. The charismatic German creator had been an important figure for Goodwin since she first encountered his work in the 1970s. She admired his use of non-art materials with strong affective associations, such as felt and fat, whose physicality recalled the body, registering meaning emotionally and experientially. “What Goodwin shares with Beuys,” the critic Georges Bogardi wrote, “is the freedom to leap categories, and that elliptical use of imagery for suggesting feelings rather than explaining or depicting them. Both achieve this by possessing a visceral empathy for substances, an instinctive understanding of how raw material already connotes, even before the artist’s hand has begun to shape it.”

Goodwin demonstrated a finely tuned degree of material choice and an appetite for experimentation throughout her oeuvre. Her continual innovation and her search for an expressive materiality—whether in prints, drawing, or installation—came in part from her belief that an image could never adequately convey the pervasive complexity of the human condition, a question to which she was inexorably drawn.

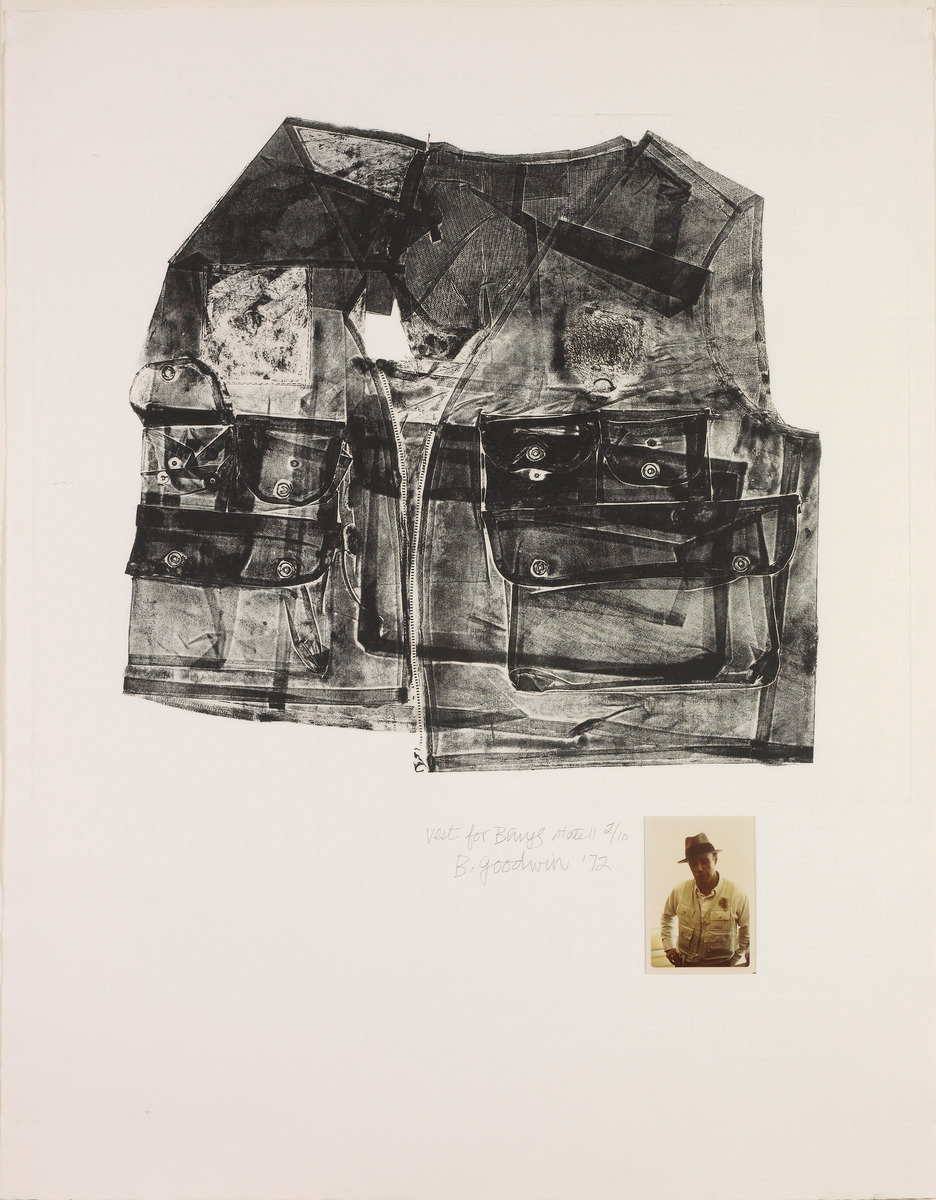

Her desire to create greater visual resonance surfaced early in the material transformations she pursued as she completed her Vest series in the early 1970s, moving over a three-year period from prints, to amalgams of printing and drawing, to plaster casting and collage. Eventually she buried several vests in earth, enclosing them in a vitrine to reveal sedimentary layers. During this period, she made prints of several other found objects, including Gloves One, 1970, and Nest with Hanging Grass (Nest Six), 1973.

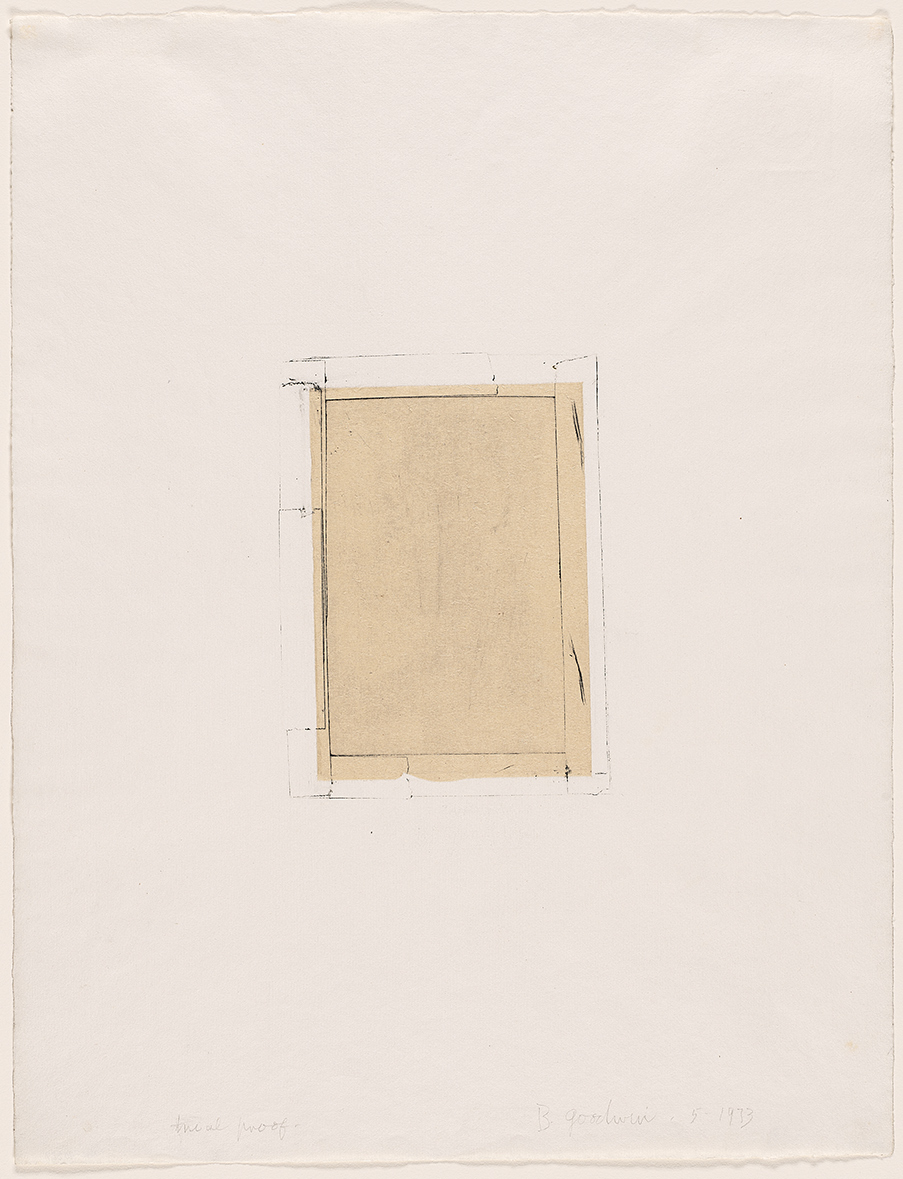

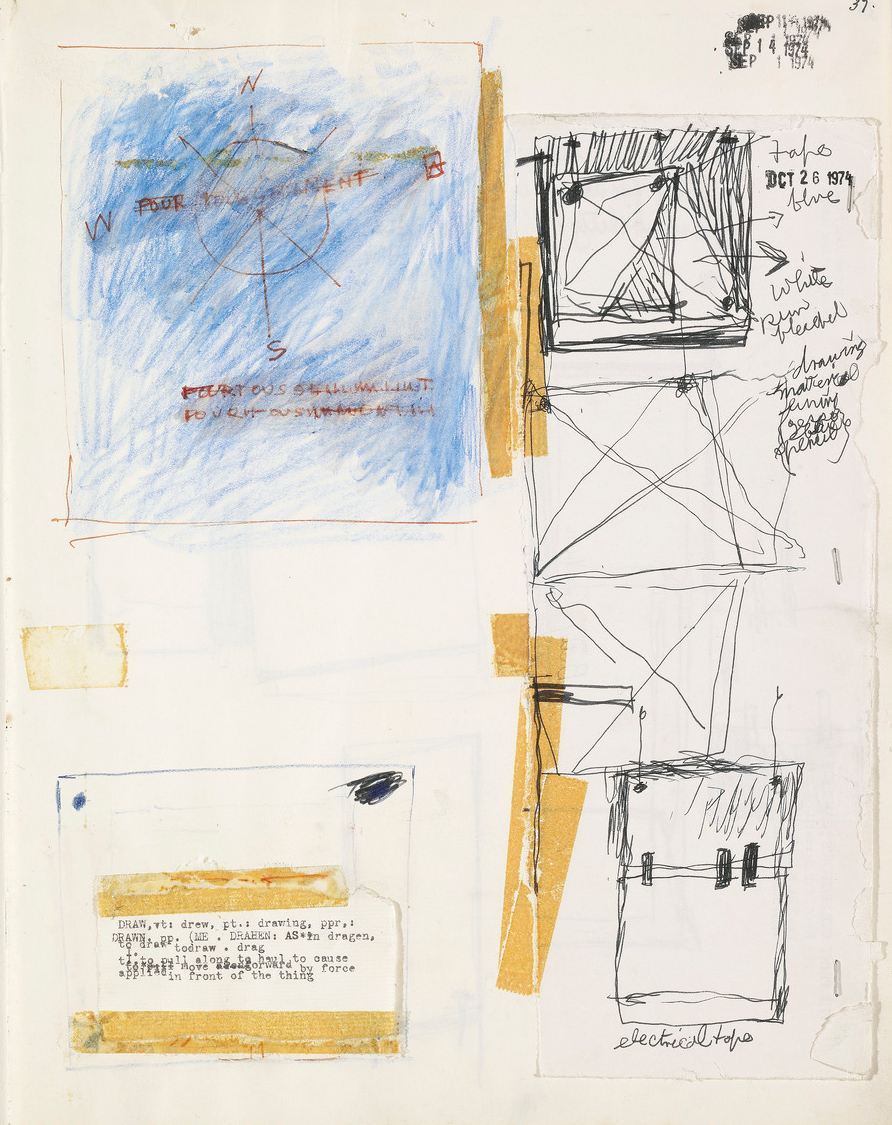

Goodwin began searching for more challenging and varied methods of printing when she composed her Notes series of etchings from 1973 to 1974, using compound processes of layering that presaged more radical departures in her use of materials to come. Combining paper laminates and imprinting materials such as tape, staples, and wire, she made spare images of tenuousness that seem barely held together, as in Note One, 1973. Curator Rosemarie Tovell describes the intricacy of the process when discussing Goodwin’s Note One: “Japan paper is laminated to white etching paper. A copper plate, matching the size of the Japan laminate is Scotch-taped to another plate that will extend beyond the edges of the white paper. The smaller plates with tape are inked and wiped nearly clean. When printed on the Japan paper laminate, it will look as if the Japan paper, the ‘note‘ element, is Scotch-taped to the white paper.”

Beyond Printmaking: Materiality & Metaphor

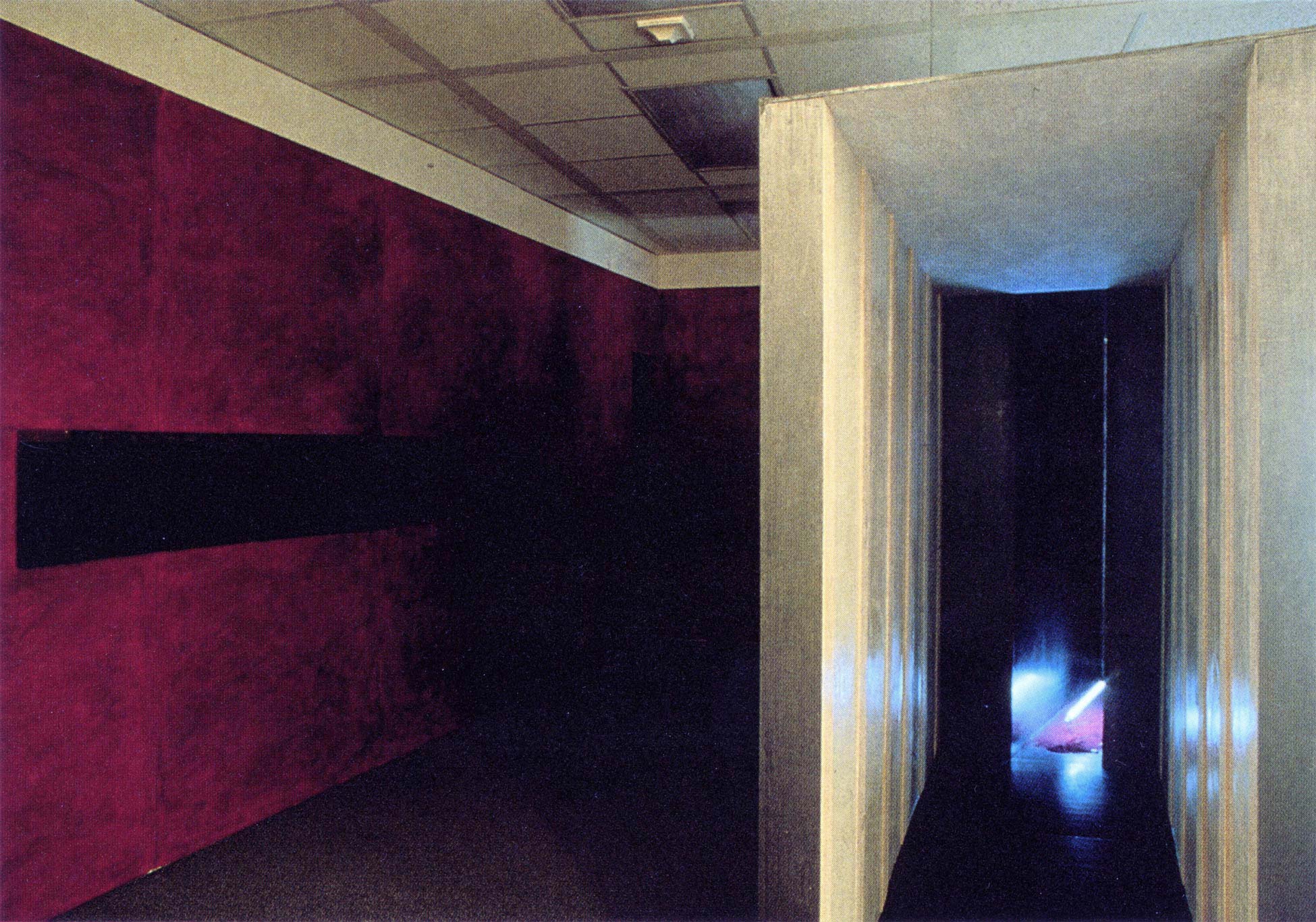

Goodwin indulged in a broadening range of materials when she left the technical bounds of printmaking. Her reworking of used tarpaulins in the mid-1970s, as seen in Tarpaulin No. 3, 1975, marked a pivotal phase of experimentation with scale and a move away from conventional art materials. Already attracted to lingering traces of life, she altered perceptions of disused spaces in her installations, adding her own structural interventions. Critic Nancy Tousely commented that the experience of the 1980 installation Passage in a Red Field, Goodwin’s first installation in a museum, was like being in a painting, while critic Chantal Pontbriand claimed this work was painting tested to its limits. These comments testify how Goodwin’s hand is evident in the surfaces she enriched with a repertoire of marks and painterly treatments.

Goodwin also introduced steel, wax, raw pigment, and neon lights in Passage in a Red Field, evocative materials that recall the alchemical dynamism present in the work of artists associated at the time with the European Arte Povera movement. In the interior of a constructed passage, she improvised to create a milky translucence, achieving her ends with regular paraffin wax made for sealing jam jars and melting hundreds of pounds of these domestic wax tablets in a kitchen deep fryer. In her Mentana Street Project, 1979, she lined a passage with clay, creating a cool, matte grey corridor, and in contrast used luminous gold paint on its exterior. In another room, Goodwin drew the life out of plaster walls by laboriously tracing graphite over their surface, as if making a rubbing of an existing relief image.

Major projects such as these invited experimentation with methods and materials, and this spirit of invention followed Goodwin in the approaches she took for her large drawings. Wax, charcoal, pastel, graphite, oil stick, and colour washes recur in combinations throughout the drawings for which she later became best known. She integrated the heaviness of steel bars in some of her drawings, improbably melding the solidity, weight, and force of metal with the lightness of paper to emphasize the vulnerability of the bodies she was depicting.

Goodwin’s Swimmers series, 1982–88, presented several technical challenges, not least of all their ambitious dimensions. These drawings became renowned not only for their scale and the arresting presence of bodies, but also for the artist’s achievement of the visual effect of water as an enveloping medium. Several Red Cross lifesaving manuals and photographs of her husband, Martin, swimming in the river by their Sainte-Adèle home, are among Goodwin’s papers of this period. She evidently studied them to understand the posture of bodies floating or drowning and of those saving them, sometimes depicting two figures in resulting drawings.

While completing a series of smaller drawings in which swimming figures were more conventionally represented moving through water, Goodwin was also working on the largest sheets of paper she could obtain, soaking them with a wash of turpentine to instill a degree of transparency that engulfed the figure in a watery field. As she spent days inhaling the fumes, the liberal use of turpentine soon had ill effects on her health. After exhaustive research, she found the oversize dimensions and transparency she sought in rolls of Mylar and other similar translucent materials manufactured in larger dimensions than standard paper and used by architects for large plans. As drawing became her primary medium, Goodwin continued to combine materials, introducing charcoal dust and tar to darken her figures and better convey the gravity of emotional as well as physical circumstances; this approach is evident in both her Carbon series, 1986, and the Distorted Events series, which spanned from the late 1980s through the 1990s. Goodwin also had photographs that inspired her enlarged and printed on photosensitive Mylar to use as the initial base to create her own images with paints and oil stick, as in the Nerves series, 1993–95.

Found Objects

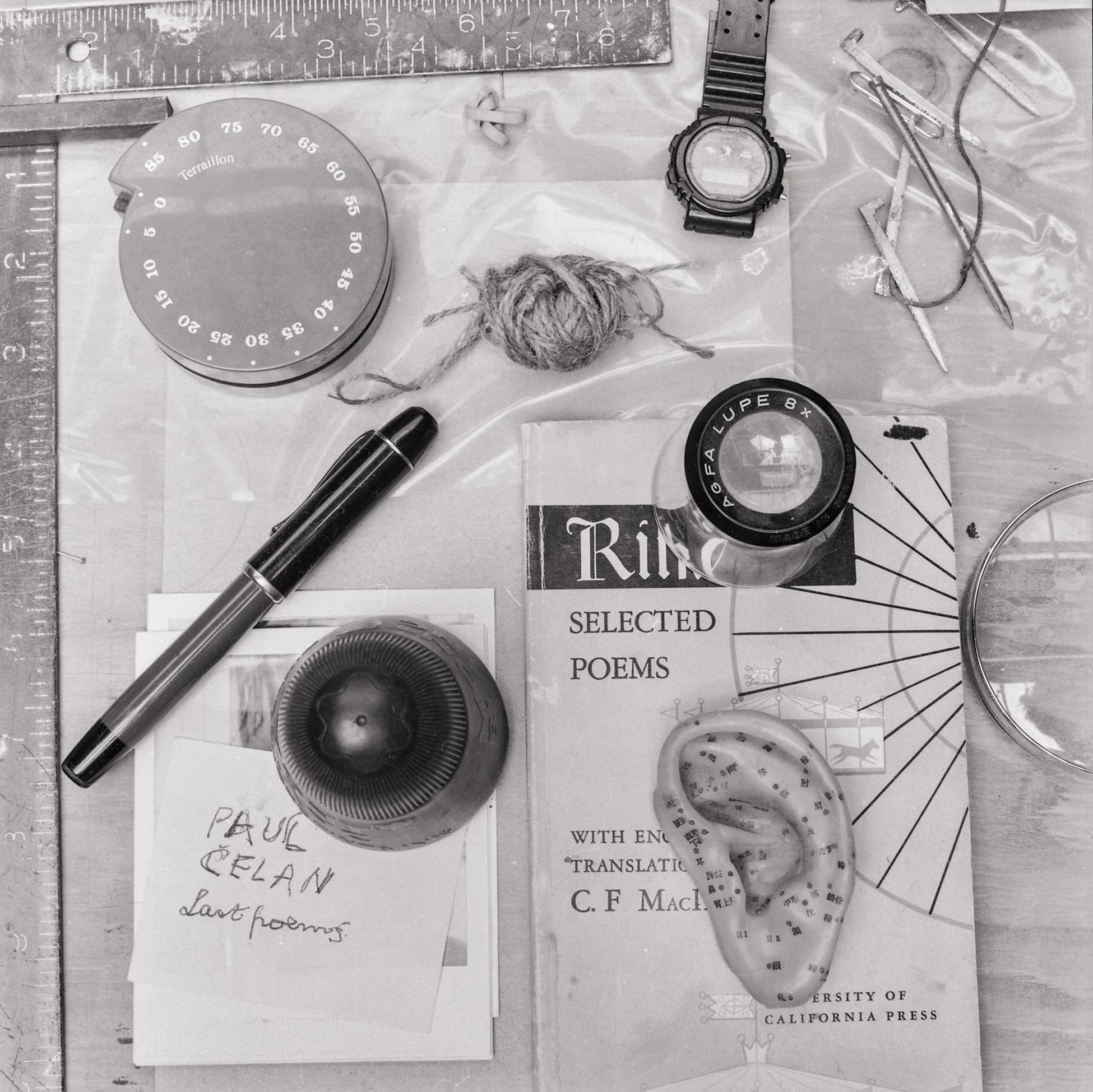

Goodwin’s lifelong practice of collecting ordinary objects that appealed to her and arranging them with evident aesthetic pleasure was reflected in her home and studio. In the last twenty years of her life, her purpose-built milieu gave her the space to display her collections on large tables, where she laid them out, classified in loose categories, and could adjust relationships between objects as she observed them over time. She often spoke of absorbing the aura of these objects—a range as varied as stones, bits of broken metal and wire, bones, dead birds, and a leather glove shrunk in the wash. Goodwin’s collections functioned as a kind of material library, a source of hidden narratives or subliminal knowledge from which she could choose when she felt a connection to the work she was making nearby.

For Goodwin, the presence of the submerged, rather than the manifest, emitted a particular energy, a latency she sought to create in her work. It was that interest in unknown or only partially revealed contents that she explored in her etchings of parcels, such as Parcel Seven, c.October 1969, and was writ large in her fascination with the tarpaulins covering the contents of transport trucks. “I identify with parcels wrapped up, unknown—invisible to viewers,” she wrote.

That her vest works of the early 1970s issued directly from real objects fulfilled her desire to go beyond depiction in her work; this led to her innovative use of found objects and images as material forces she could harness to her own ends. Acknowledging the liberating permission that developments in Pop art gave her, she wrote in October 1970, “I’ve always had a communion with objects but now it’s more at one with my work—my life is more of a whole—if contemporary art has done anything it’s brought us out of the ivory tower right down to open our eyes and see the thereness of what we are surrounded by. [Claes] Oldenburg, [Jim] Dine, [Jasper] Johns certainly freed me.”

On one of her many trips with her gallerist Roger Bellemare during the 1970s, Goodwin went to a performance by Joseph Beuys at New York’s Ronald Feldman Gallery, where she took several photographs of the artist wearing his signature fisherman’s vest and fedora. Later, she would incorporate one of these snapshots with a print of a similar vest, in Vest for Beuys, 1972. Photographs—found as well as personal ones—increasingly played a role in her work, becoming rudimentary bases that she worked into her own drawings.

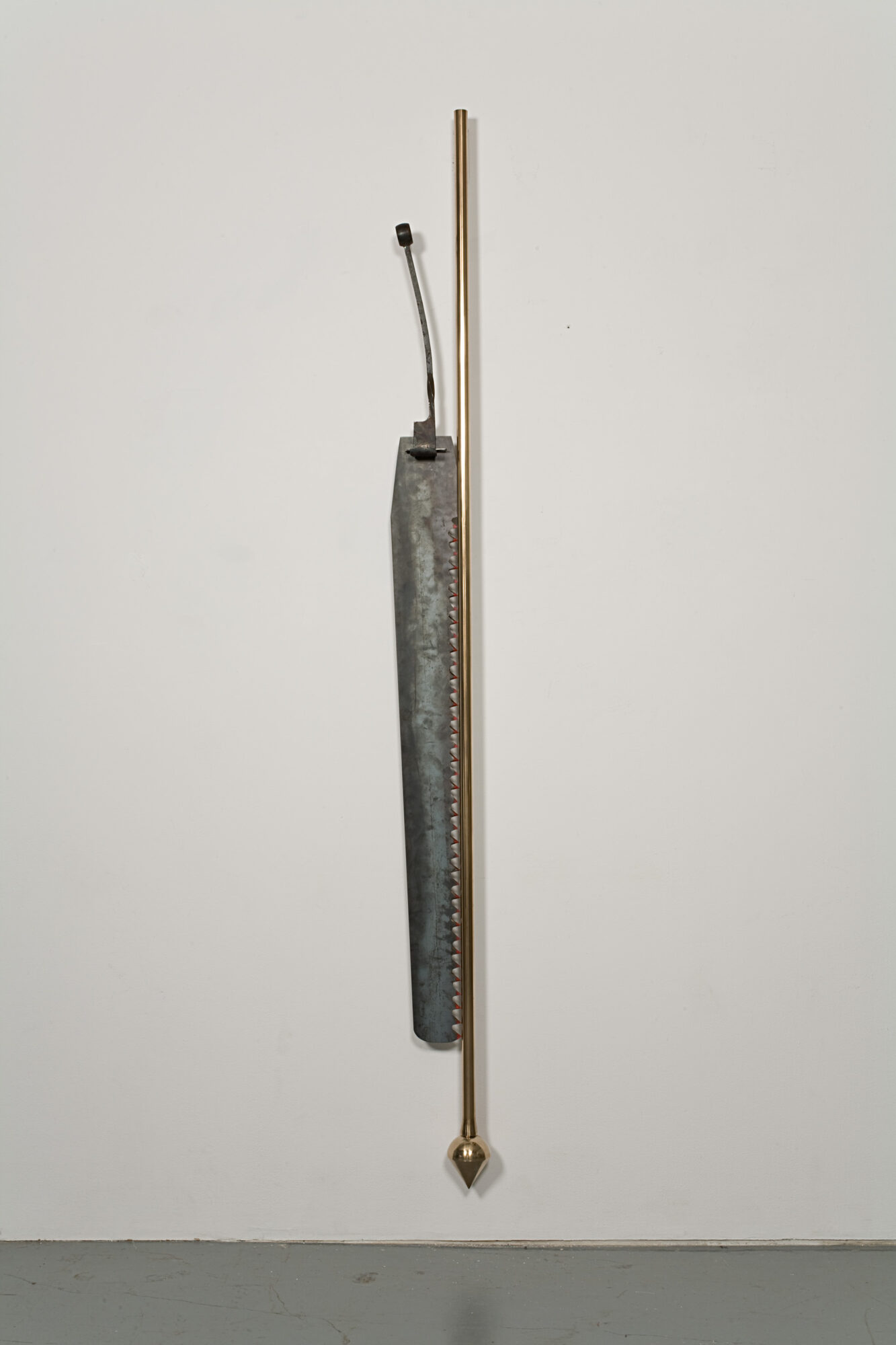

Goodwin incorporated found steel elements in drawings, bringing to some of her most difficult images of oppression the weight of an intransigent, immoveable force. She was inspired by the material and metaphorical dialogue created in the charged symbolic juxtaposition of found objects, such as the threatening teeth of a long antique saw blade she had kept in the studio for more than twenty years, placed against an ominously large, new brass pendulum she had fabricated for her piece Unceasingly, 2004–5, or the ancient mysteries of a narwhal’s tusk seen near one of her drawings of the spiral of time.

Working across Media

Goodwin’s installations created between 1977 and 1982 straddled several media, breaking down distinct categories and offering new relations between them. Although they no longer exist, these projects were undoubtedly instrumental in Goodwin’s later development of approaches to works that were neither strictly sculptural nor defined directly by familiar techniques of painting, drawing, and printmaking.

The first of her installations, Four Columns to Support a Room (projet de la rue Clark), 1977, which was not made for public viewing, was realized in a disused loft she rented in an industrial building on Montreal’s Clark Street in 1977. Her intervention produced a shrine-like space within thick paper hung as walls enclosing four architectural columns. For Goodwin, this creation of a large sculptural volume was an important step toward working three-dimensionally. She evidently gave particular importance to this first venture into three-dimensional space, retaining a series of mounted photographs hand-finished with oil paint: in essence, a two-dimensional record of her process.

A decade later, after completing several critically recognized installations, in Distorted Events, No. 2, 1989–90, Goodwin brings two- and three-dimensional space into a forceful collision of unlikely materials. Working with a ground of white ceramic tiles mounted on aluminum, she established a chilling setting, implying a clinically sparse room. An image of an empty chair is smudged in tar against the tiles. The chair appears to hover between flat solidity and displacement, and above it a burst of yellow oil pastel rises or escapes like a vestige of energy, a departed soul. Two metal bars rest ominously against the edge of the thickly drawn surface of the chair. Here, Goodwin conveys a material struggle between two and three dimensions, as if seeking a visual experience of distortion equal to the gravity of events that are indicated to have taken place in that virtual room. The figure is implied through its troubling absence.

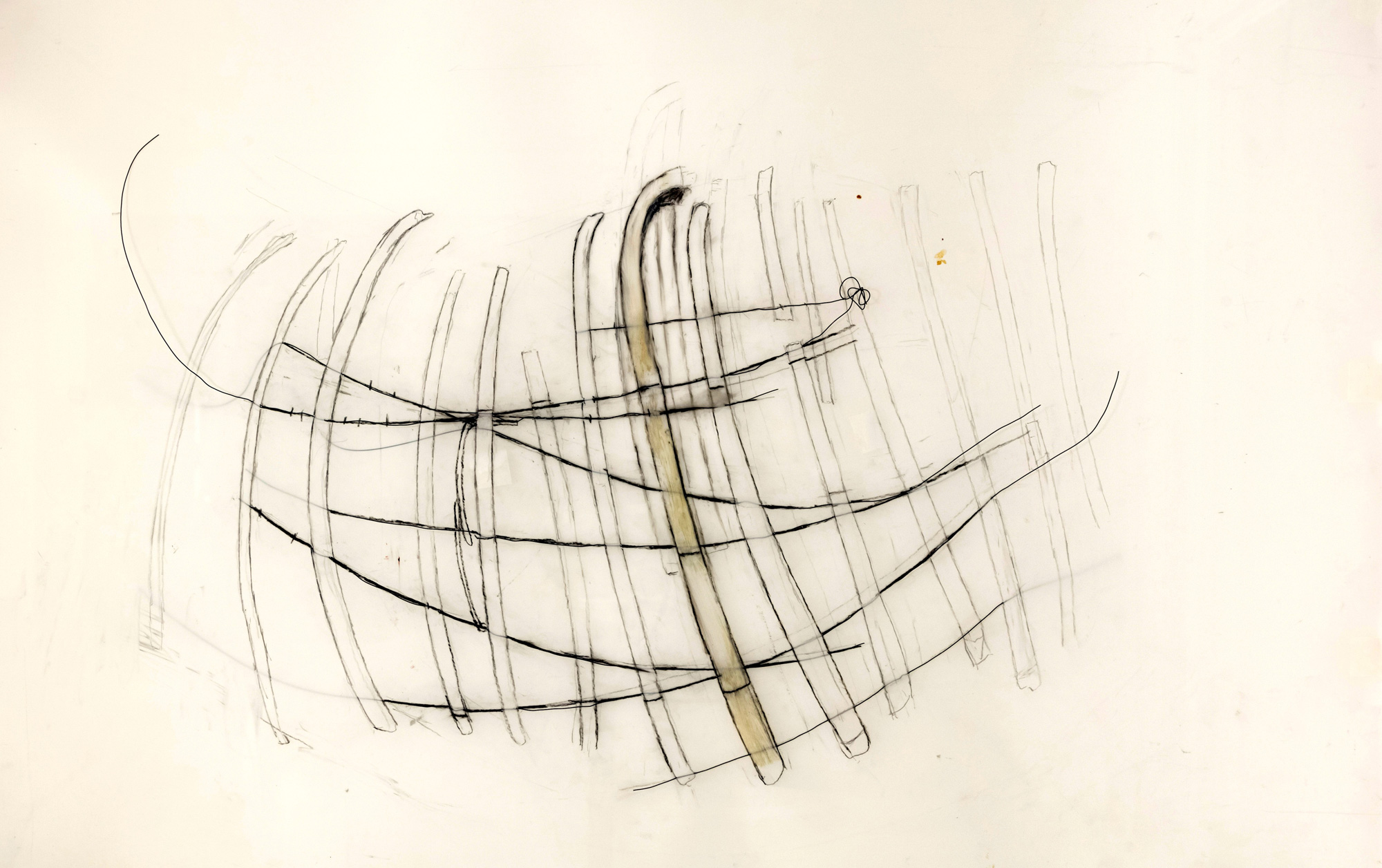

In accordance with her repeated search for ways to bring the sensation of difficult realities more concretely into her work, during the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, Goodwin made technical and material leaps in her exploration of the potential of drawing. She began to incorporate other elements such as fine wires that matched the fragility of charcoal and pencil lines, as if, again, she had found a two-dimensional representation insufficient. The drawings, such as Wires of Investigation, 1992, seem a world apart from the 1988–89 Steel Notes tablets, say, which were created with iron filings and magnets, yet they similarly emphasize a tenuous reality on the verge of being upset by its own imbalance of opposing material forces.

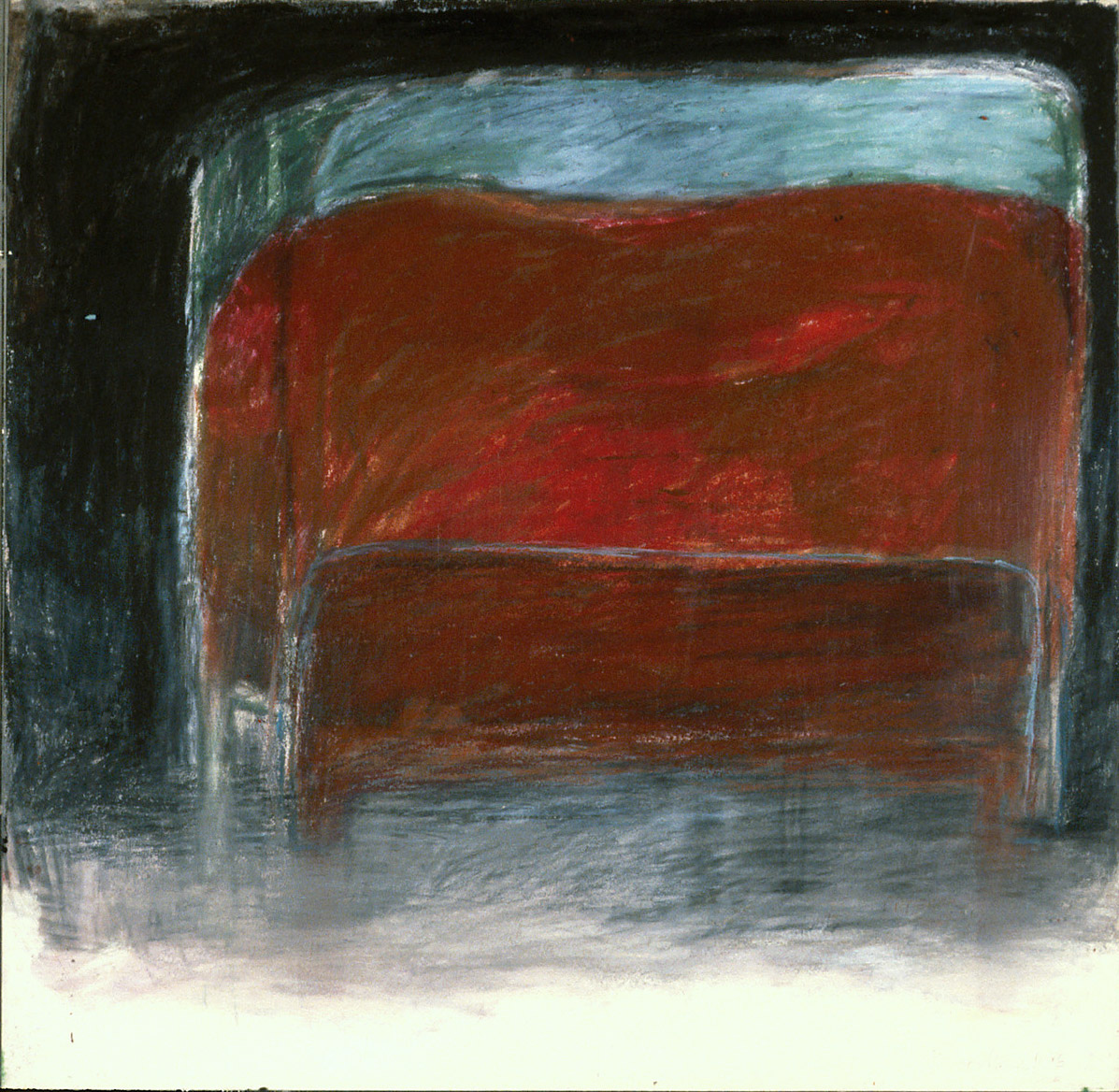

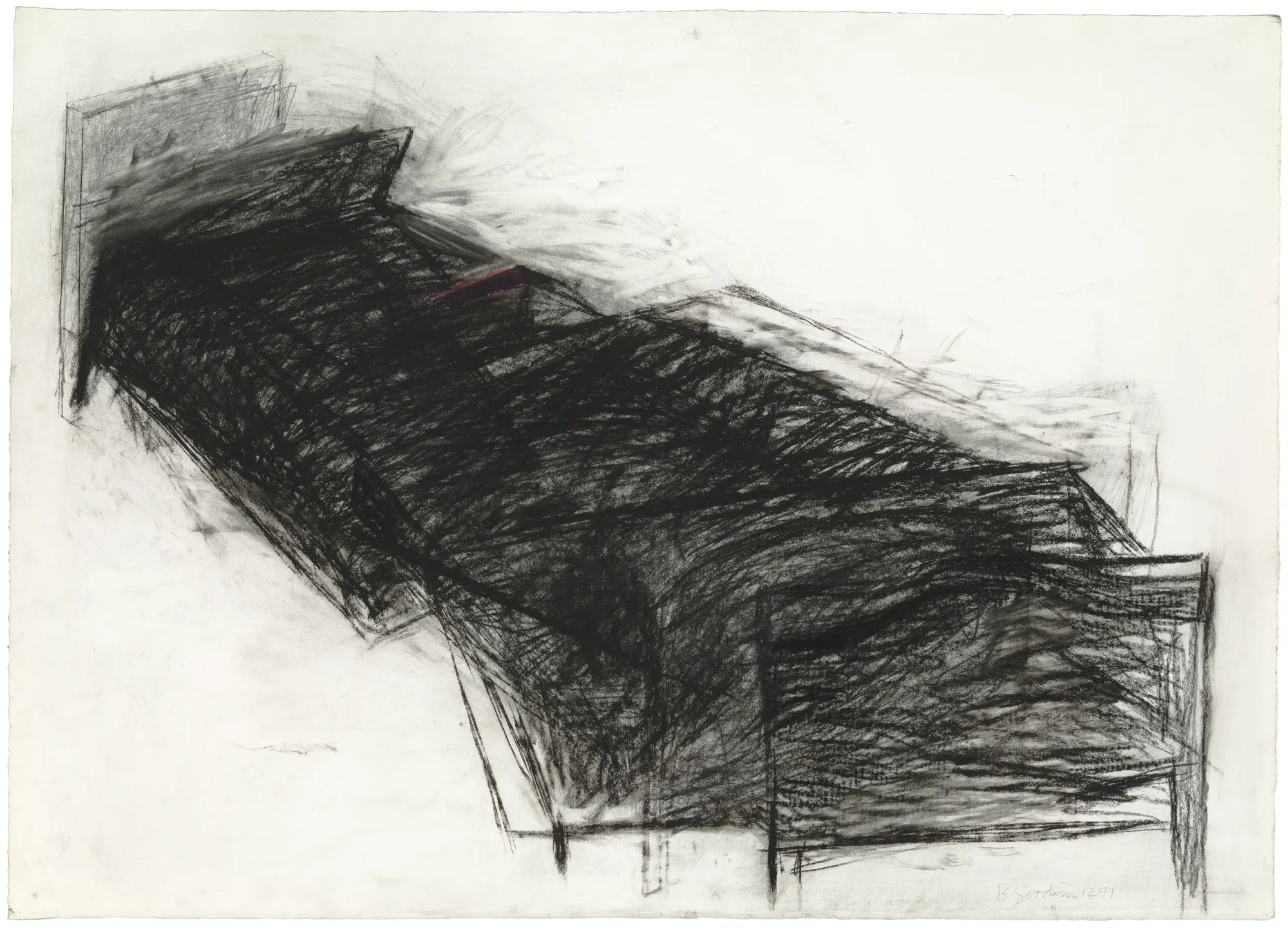

In later works, Goodwin continued to freely mix materials and techniques to realize her images. Her Nerves series, 1993–95, several works from her Mémoire du corps (The Memory of the Body) series, 1990–95, and her Beyond Chaos drawings, 1998–99, incorporate photography printed in black and white on Mylar as a base or trace, over which she elaborated her own selective detail, adding drawn figures and using colour as accent. In Untitled (La mémoire du corps), 1995, she has a photograph of a bare steel bed enlarged and printed with an ominous shrouded form hovering above it. In her notebooks, Goodwin made several references to the bed as a site of birth, sleep, intimacy, illness, dreams, and death. It reappears as a constant in her visual vocabulary, a repetition with variation, and a return in several media, whether in the colourful drawing Untitled (Bed), 1976, or the extended series of drawings related to River Piece, 1978, her sculpture commission at Artpark in Lewiston, New York, which traced geological time in shifting formation of the riverbed along an embankment of the Niagara River.

Process as Technique

Goodwin’s notebooks were an essential resource as she honed her vision through several phases in her art. Described by curator Georgiana Uhlyarik as Goodwin’s portable studio and creative mine, the more than one hundred notebooks she filled over the course of her career were integral to her process of conceiving a work. In their pages, accumulated observations, rudimentary sketches, and phrases from authors whose writing resonated with her coalesced over time. Goodwin returned to her notebooks for inspiration, often seizing on an idea that had lain dormant—sometimes for years—until the moment she trusted her intuition and ability to give it form as a work of art.

Reflecting on her way of working, Goodwin remarked,

It has become apparent to me that I work in a sort of spiral pattern. I burrow as deeply as I can into an idea which reveals more of itself in the process. Always seeking the essence—as the series comes to an end it seems to pick up another kind of energy and moves into another series. A constant overlapping consciously or unconsciously taking advantage of chance. Nothing comes directly. I zig zag into the finished work, and it is always difficult for me to use the finality of the word finished.

This cyclical pattern of reconsidering a subject with expanded meaning through several attempts is found throughout Goodwin’s oeuvre. She revisited images and ideas both in her notebooks and as she delved more deeply into the subjects that compelled her. In her many protracted series, each attempt to grasp the essence she sought was subjected to an additive material process that led to the next work. The term “process art” has been applied to artists who consciously expose in their work the labour-intensive procedures used to make it. In contrast, Goodwin’s process, often stretching over decades, is witness to her struggle to find her way from idea to appropriate form. As she said,

The working process itself is a non-verbal battle. There are times when everything just seems so chaotic and nothing really makes sense to you. Things can happen to a drawing if you take the risk of wiping into it, which is also drawing. You wipe it off and out of a frenzy of despair you start again and very often it is at those times that something will come that you really did not plan on. Something inherent in the process takes over and returns something to you.

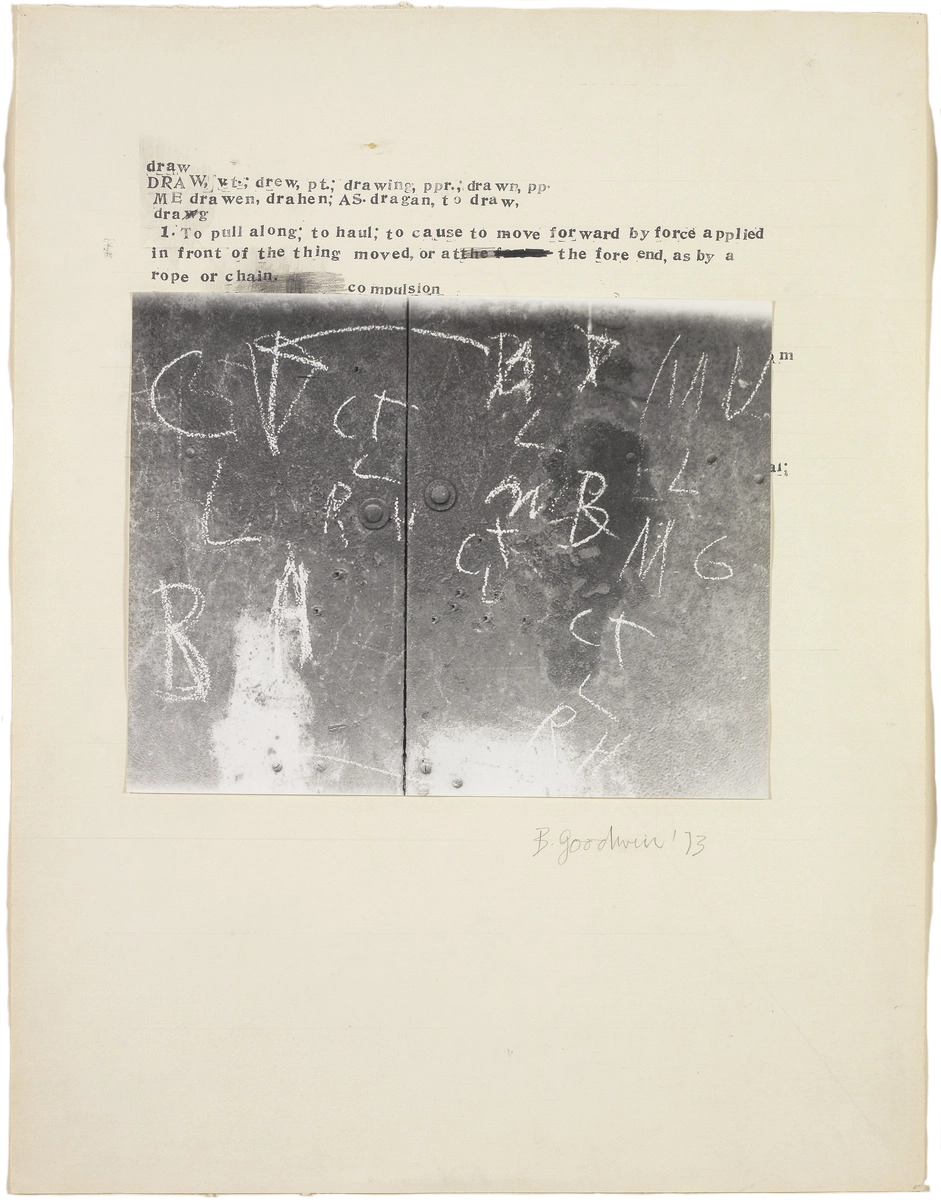

Goodwin’s early etching plates show evidence of being used and reused, as was common practice; however, prior use left a trace, no matter how faint, which she welcomed. She replicated this habit of working in stages in her approach to drawing. She seemed to understand drawing as an act where process and technique meet. A simple dictionary definition of the verb “to draw,” already recorded in her notebooks when it was introduced as text in her Notes print series of the early 1970s, indicates the breadth of meanings, which clearly appealed to Goodwin’s thoughts about her process: to represent by lines drawn on a plain surface; to eviscerate; to pull out the bowels of (as to draw poultry); to let run out; to extract (as to draw wine from a cask); to draw blood from a vein; to inhale, to take into the lungs (as, to draw breath).

In Goodwin’s hands, drawing was ceaselessly active, open to spontaneous incident and, in this regard, had the potential to supersede static representation. Her drawings possess an unpremeditated quality. She allowed—even welcomed—the incidental that could occur mid-process to introduce new challenges and become the instigation for the next steps.

Characteristically, Goodwin worked through an idea within a piece or over several pieces before moving on. Immersed in the process of drawing, she occasionally appended sections as the work progressed. “Sheets of paper are added one on top of the other,” wrote critic and academic Laurier Lacroix, “combining both to re-establish the equilibrium of the image, as well as to allow it to develop more freely in space.” The writer Gerald Hannon noticed while visiting Goodwin’s studio for an interview that she made a small adjustment to a drawing as she walked by it, as if unable to resist attending immediately to something she noticed out of the corner of her eye and found missing.

Throughout her career, this organic process became inseparable from the techniques Goodwin resorted to in the course of making a work. The emergence of an image from within the process of its making gave her permission to introduce whatever medium best instilled the visceral impact she desired. The further she pushed her experimentation, the closer she came to making a transition from one set of works to another, or a shift to an entirely different visual vernacular.

Curator Cindy Richmond wrote eloquently of Goodwin’s process, noting how drawing was “both a medium for making art and a method of investigation…. Ideas cling like magnets to other ideas. Together these fragments of information form a network, a map of how Goodwin apprehends the world. Eventually, if a strong connection is made, Goodwin may incorporate elements from an object or network of objects into a work.” A painstaking and ever-changing process, where emotional investment and physical efforts are inseparable from their material manifestation, fuelled Goodwin’s pursuit of the unique range of techniques and materials that served her singular vision.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements