Betty Goodwin’s innovations with printmaking, including her use of found objects, received significant recognition in the early 1970s, a time when a loosening of artistic categories was gathering momentum. Video, performance, installation, and feminist practices were challenging prevailing definitions of art. Over subsequent decades, Goodwin’s inventive approach to figuration assured her a unique position at a time when the body was becoming central to socio-political debates in the wake of the AIDS crisis. An emerging generation of artists was also returning to figuration, often responding to popular culture, and using photography. Goodwin made her greatest contribution through the importance she gave to drawing as a contemporary medium.

The Artist in the World

Goodwin was resolutely a studio artist who tended to work alone and closely guarded her time in the studio. She often turned to her notebooks for inspiration, finding phrases or images that provided the beginning point for new work, even as the world beyond pressed more and more on her consciousness. As much as she was a loner, Goodwin was not a recluse. Though never associated with a group or artistic movement, she was keenly interested in what other artists were doing, and she was a frequent presence at art events in the Montreal scene. Goodwin was also curious about what artists were doing outside Canada, as is evident in the notes and snapshots she took when she visited exhibitions on frequent trips to New York and Europe. And, for her part, she was revered by younger artists and likewise followed their work, lending her support when sought to artists such as Spring Hurlbut (b.1952) and Jana Sterbak (b.1955). The critical impact of her large drawings was also validating for other Canadian artists such as John Scott (1950–2022) and Shelagh Keeley (b.1954), who were dedicating their practices primarily to drawing.

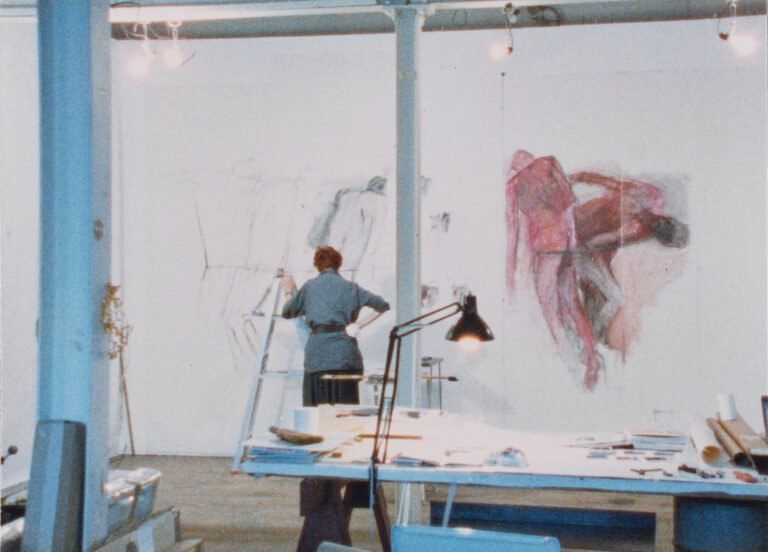

Salah Bachir, a major collector of Goodwin’s work, described the experience of his first visit to her Montreal studio on Avenue Coloniale as “overwhelming, almost like a pilgrimage to an inner sanctum.” Several large tables in the centre of the room accommodated carefully arranged collections of found objects, including stones and scrap metal, that fuelled her exploration of the expressive potential of materials from within an ordered world of her own. Between these tables, surrounded by piles of publications, newspaper clippings, and photographs that she saved for their information and images about world events, Goodwin placed two chairs—one for herself to survey her surroundings and contemplate work in progress, the other for the rare visitor.

Though always intensely focused on her art, by the late 1980s, Goodwin was growing more engaged with the wider world as the art community and society at large were gripped by the AIDS crisis and the ensuing politics of sexuality and the body. She developed her work in this context and was acutely aware of the social and political upheavals reshaping art and the world around her. Her drawings, including Two Hooded Figures with Chair, No. 2, 1988, and Figure with Chair, No. 1, 1988, were beginning to reflect her habit of following media reports from around the world and immersing herself in the reality of atrocities borne of war and famine as well as in reports of the rapacious degradation of the natural environment.

Decades before it became an urgent issue, Goodwin was gathering articles on the effects of climate change. Her papers also contain clippings of photos of elephant herds dying out due to tusk poaching, and articles on drought and pollution, the Tiananmen Square massacre, Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu’s destroyed palace in Bucharest, and famine in Somalia. A wide range of topics caught her attention. Goodwin was never one to give up. Even as her handwriting began to deteriorate in the early 2000s, the words “determination” and “despair” continued to appear in her notebooks. Frequently using her given name, Béla, over the decades Goodwin exhorted herself in those pages to push further, to hold onto her willpower, to be in the world when she felt personal and political circumstances too great to bear. While her work increasingly attests to a world in disarray and emphasizes the fragility of life, it is not reducible to a lament. Instead, it is a vehicle for confronting complex emotions in the face of bleak events.

Between Politics & Poetics

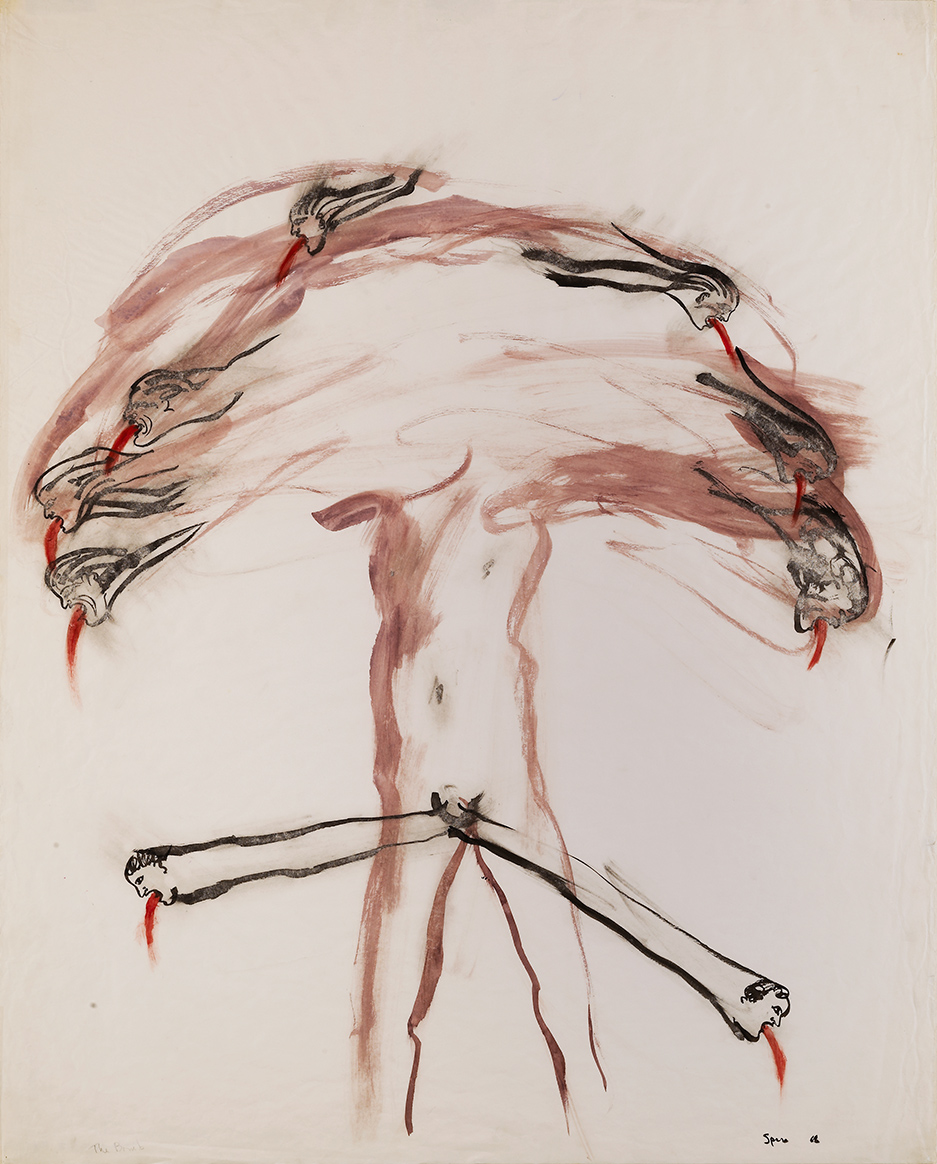

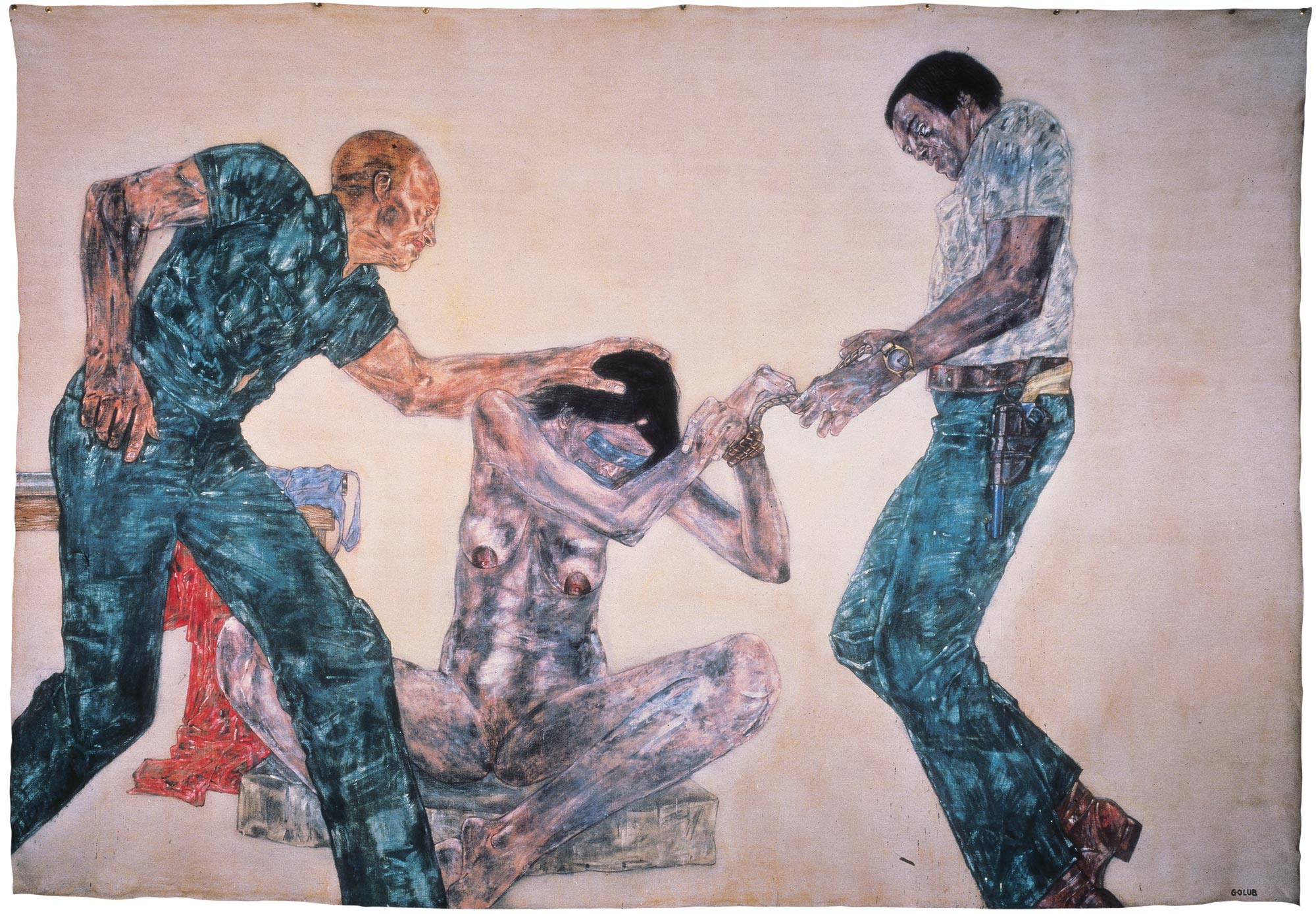

While current events influenced Goodwin’s art, her methods and intentions differed markedly from those of contemporary artists she admired and felt an affinity with, such as American artists Nancy Spero (1926–2009) and Leon Golub (1922–2004), whose works were overtly political and included specific references to the Vietnam War and nuclear holocaust. Nor did she actively participate in the feminism that, for example, spurred Spero in 1976 to make her epic narrative drawing Torture of Women, which addresses the universal subjugation of women, and was derived from a 1975 Amnesty International report. No matter how affected Goodwin was by unrest in the external world, the power of her work was rooted in her emotional responses to events rather than in an articulated political stance. Her empathy arose from deep personal recesses of painful experience, but the impact of her work across several media lay in her ability to channel wider, more universal traumas, without summoning specific narratives. Like Spero, Goodwin became notable for the unsparing directness of her imagery. Both women made important claims for the legitimacy of paper and drawing amid the lingering traditionally held belief that painting was the most legitimate fine art medium: Goodwin with her oversize materially rich drawings, and Spero with her use of hand printing, text, and collage in monumental scrolls.

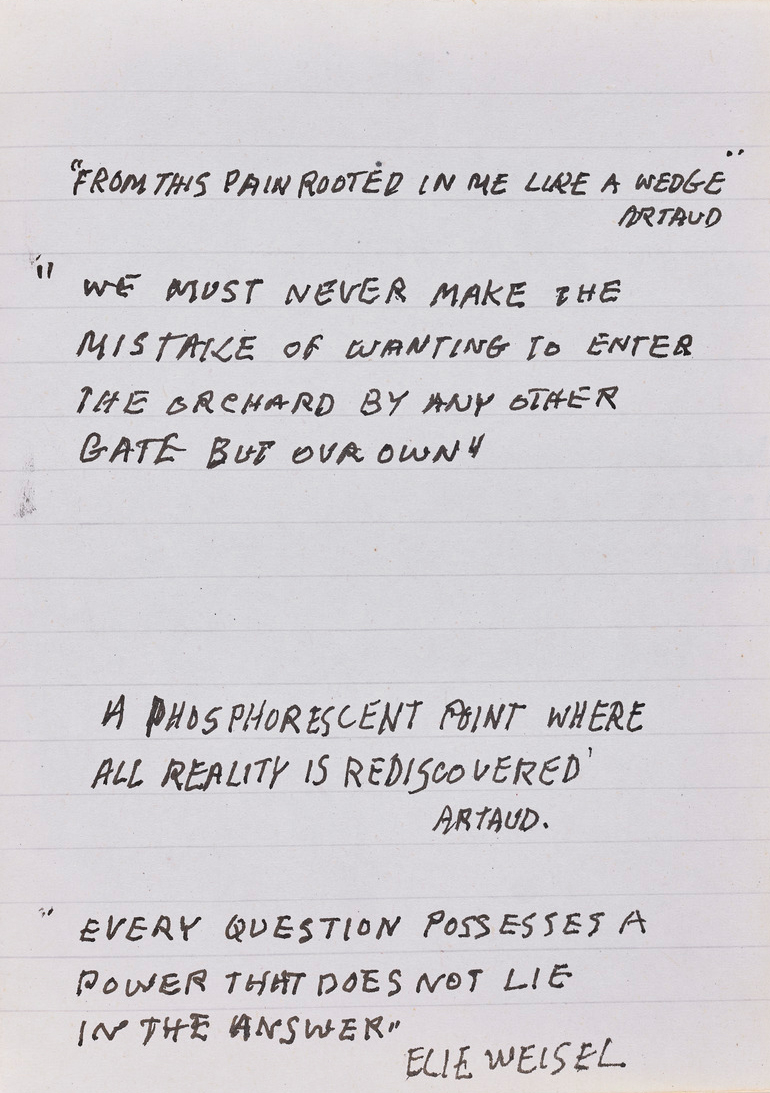

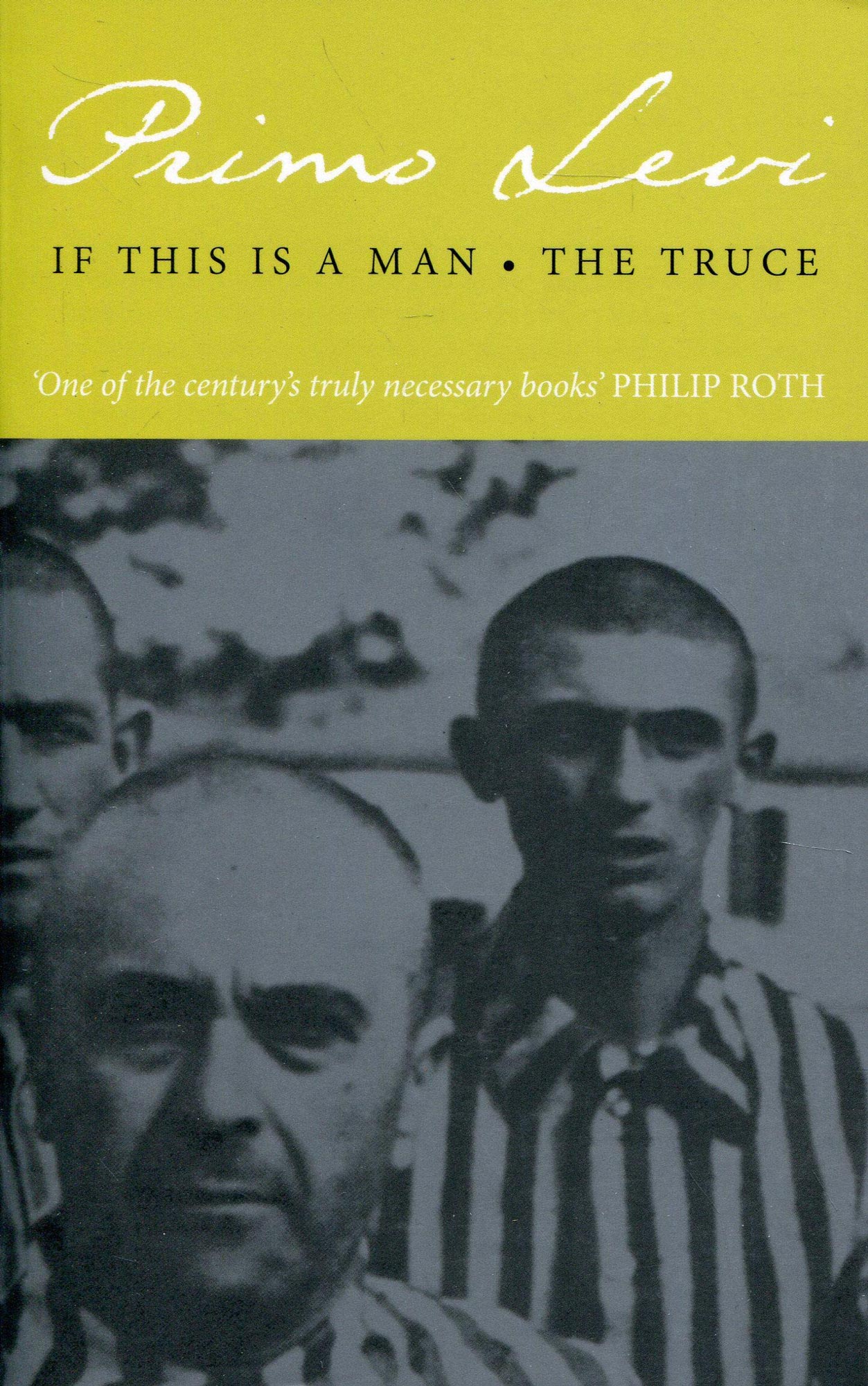

Goodwin frequently inscribed her drawings with phrases quoted from modern authors she was reading. She identified with the tragicomic existential predicaments of the characters of Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) and the radical experiential realism proposed by Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) in his Theatre of Cruelty. She was also moved by the poetry of the American poet and human rights activist Carolyn Forché (b.1950), whose words captured a world in the throes of dictatorial violence. Closer to her Jewish heritage, Goodwin turned frequently to texts by Holocaust survivors Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi. Though she and her husband, Martin, were not practising Jews, the history of her people resonated in her alongside current stories of cruelty and inhuman disregard for life that she encountered in the nightly news.

Goodwin quoted and requoted text fragments from these varied authors’ writings in her work, notably in her public art commission Triptych, 1990–91, made for the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, in the Jean-Nöel Desmarais wing, where a large bronze ear and a megaphone form face each other high up on the walls of a passage-like atrium while phrases drawn from Forché and Wiesel are inscribed on the floor below. The line from Forché’s poetry, “do you know how long it takes / any one voice to reach another,” is also paraphrased in several drawings, attesting to Goodwin’s preoccupation with unheard voices, and the difficulty of making urgent or unwelcome communications heard.

In the 1980s, politically motivated, text-based work proliferated in the art world, exemplified by artists such as Barbara Kruger (b.1945) and Jenny Holzer (b.1950), whose works laid bare the subliminal messages of ubiquitous consumer advertising and the dominance of dehumanizing corporate culture, often with feminist overtones to their art. However, Goodwin did not use text in a conceptual way. She quoted phrases as brief peripheral indications rather than as invocations. Nor did she filter her reactions to issues of the day through language directly. Like her anonymous figurative subjects, the words are neither anecdotal nor didactic.

Goodwin was reluctant to ascribe motive or meaning to her works, preferring to avoid verbal explanations that could reduce the complexity she wished to convey. She was guided by her layered, expressive process, trusting the composition and the powerful confrontation of materials to elicit bodily sensations or mental torment. In Rooted Like a Wedge,1987, a malevolent triangle pierces the torso; in Losing Energy,1994–95, the head is detached from the body, and strands of lead fall from the mouth. The complete phrase written by Artaud that struck Goodwin begins with the words “This pain…” However, Goodwin’s trust was in the force of her imagery to embody pain. Her predilection was always to leave room for the viewer’s interpretation rather than to collapse her work into unilinear narratives or personal history. Nor did Goodwin’s distilled visual language arise as a form of advocacy; rather, it gives form to anguish and outrage in a symbolic and materially charged manner that allowed her to approach subjects that words fail to adequately describe.

Drawn in the Body

The body, whether present or implied, remained the leitmotif throughout Goodwin’s work. It was palpable in her vest, shirt, and glove prints and felt more as absence in her 1970s installations; it appeared with astounding impact in her Swimmers series, 1982–88, where she expanded the scale of her drawing with life-size presence. Throughout, her allegiance to the figure transcended narrativity in favour of a deeply material embodiment of realities she experienced in her personal life, as well as struggles in the wider world.

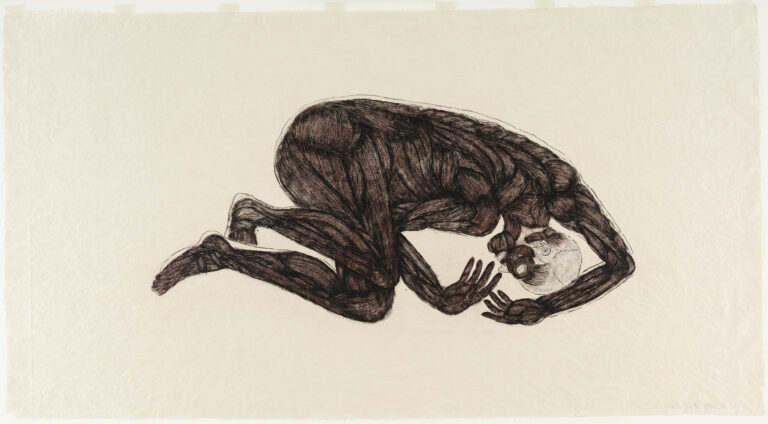

In her drawings, destined to become Goodwin’s most widely recognized contribution to contemporary art, the figure became the principal vehicle for expression of themes of memory, suffering, and inhumanity. Retracing her gestures over and over, Goodwin revels in the flexibility of the medium, in the possibility it offers of starting again, repeatedly. She erases and creates anew from remaining traces, and in so doing, she evokes both future transformation and reparation as she wrestles bodies into being. In works such as So Certain I Was, I Was a Horse, 1984–85, the repetitive movement of her hand enacts disintegration and emergence, an insistent forming and reforming. Goodwin’s bodies hover on the edge of themes that elude literal interpretation, closer to sensation than description.

She made drawing a medium of consequence when it was more commonly considered a preparatory stage toward finished works of art. In the catalogue for her first major retrospective exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, in 1987, the American critic and scholar Robert Storr, then a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, claimed a place for Goodwin, and particularly her drawings, among contemporary artists he saw as participating in an enduring tradition of Expressionism, such as Philip Guston (1913–1980), Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), Leon Golub, and Nancy Spero. Storr’s validation of Goodwin’s work in an international context was welcome. He found her drawings to be “exceptionally powerful in both conception and execution. They are, indeed, among the only works to have thus far emerged from Canada that not only reflect but also represent a significant contribution to the revival of an emotionally charged figurative art that has emanated from Europe and the United States.” Yet Storr cautioned against reading Goodwin’s work in the context of an emerging Neo-Expressionism, which he decried as being “often crude in its facture.” Goodwin’s drawings, in contrast, were “intimate in their address and delicate in their effects. The sensation they create is not one of hysteria or perceptual overload, but rather of a subtle ache, an ambiguous but cumulative unease.”

Goodwin’s drawings, such as Porteur IV (Bearer IV), 1985–86, share an affinity with the work of a younger American artist, Kiki Smith (b.1954). Smith’s bodies are, like Goodwin’s, invested in our corporeality as the ultimate place where pain, experience, and memory reside as well as the locus where our sociosexual lives are inscribed. Smith, who was also personally affected by devastating loss during the AIDS crisis, made bodies and body parts with paper, transforming its organic qualities into a delicate second skin. In the early 1990s, as the AIDS crisis raged, Goodwin, too, sought material means to convey a similar fragility and transience.

Trauma & Absence

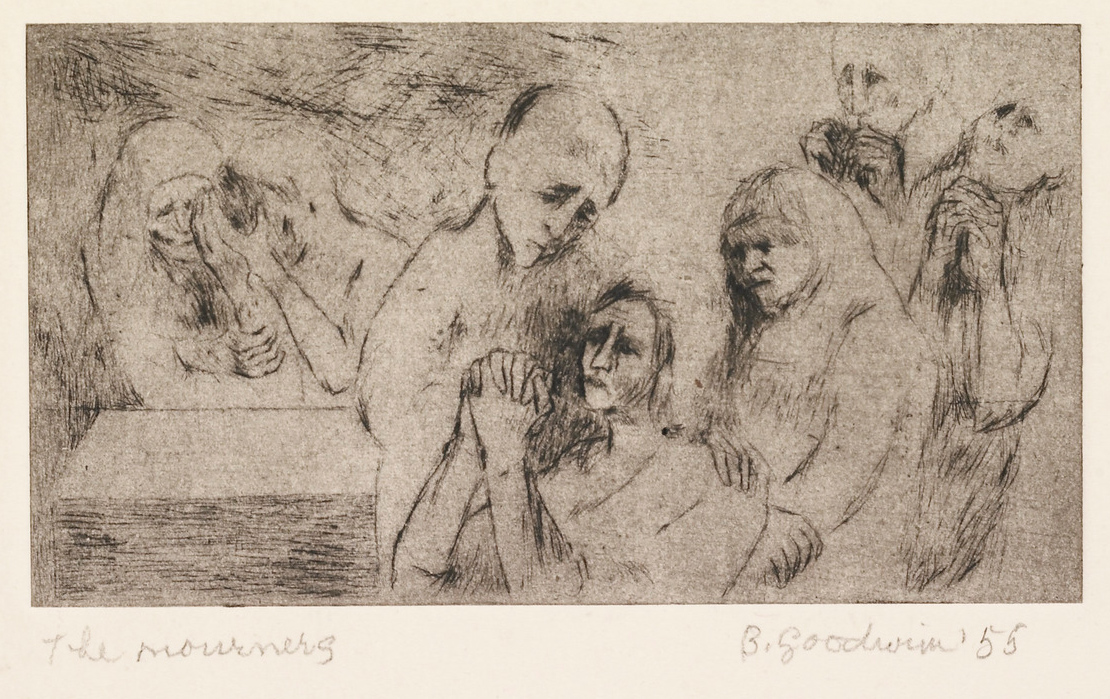

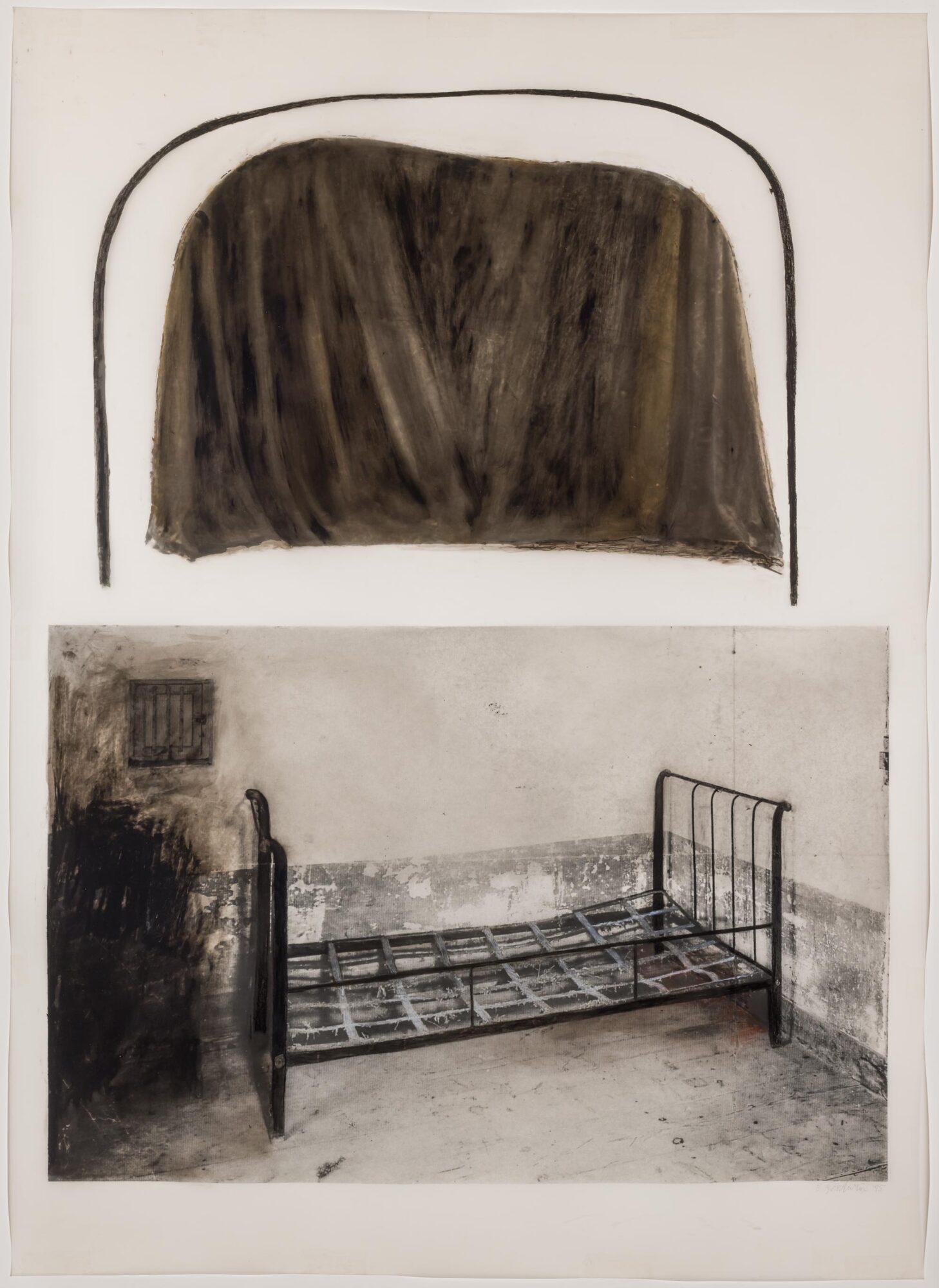

Themes of trauma and loss are evident in Goodwin’s earliest works. Her print The Mourners, 1955, captures a collective scene of grieving. The memory of war was still fresh when she made this image, and undoubtedly, Goodwin, who grew up in a Jewish home, was exposed to accounts of harrowing losses, including that of the Holocaust. Later, as she developed a visual language of her own, initially rooted in painful personal experience of grief resulting from her father’s premature death, she was increasingly able to make visceral connections to other complex spheres of struggle and loss. The notion of the imprint—of memory, of presence, of life—became a hallmark of her practice. As the media she worked in changed, she remained interested through five decades of artmaking in expressions of trauma and loss. Many of her works signal absence: the vest as a surrogate for the body; the empty spaces evocatively attended to in her installations; the bathtub, a vessel that haunted her work in the 1990s, as in La mémoire du corps XVII (The Memory of the Body XVII), 1991–92; the empty bed forms that reappear throughout her oeuvre, including in Untitled (La mémoire du corps), 1995; or the way her oppressed figures occupy a blank background as if rescued from oblivion.

In Goodwin’s drawings, bodies struggle into existence against their own fragility. If the drawings often appear tentative, her figures are nevertheless insistent. Fixing an evanescent image repeatedly through several series of drawings was Goodwin’s way of finding resolution to the expression of emotions or conditions too weighty and widespread for the bounds of language or of specific events. Like German artist Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), whom she admired, Goodwin sought a figurative and material language to encompass life reconstituted from destruction and trauma.

The latter theme is filtered through a new series of objects in her works in the 1990s. When reading a magazine article on Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), her attention was drawn to photographs of beds and bathtubs in the asylum where the painter was confined. Enlarged and printed on Mylar, these photographs formed a base that Goodwin reworked to build her own images, and they are found in a number of works within the wide range encompassed by the Mémoire du corps series. In 1992, she made a pristine white sculpture with a narrow elliptical opening, more like a sarcophagus than a bathtub but too narrow for a body. Titled Sargasso Sea, 1992, after the mysterious body of seaweed that floats like a continent in a gyre of converging ocean currents, this ghostly sculpture is less a container than a deep void, a quietly elegant and imposing form signifying absence.

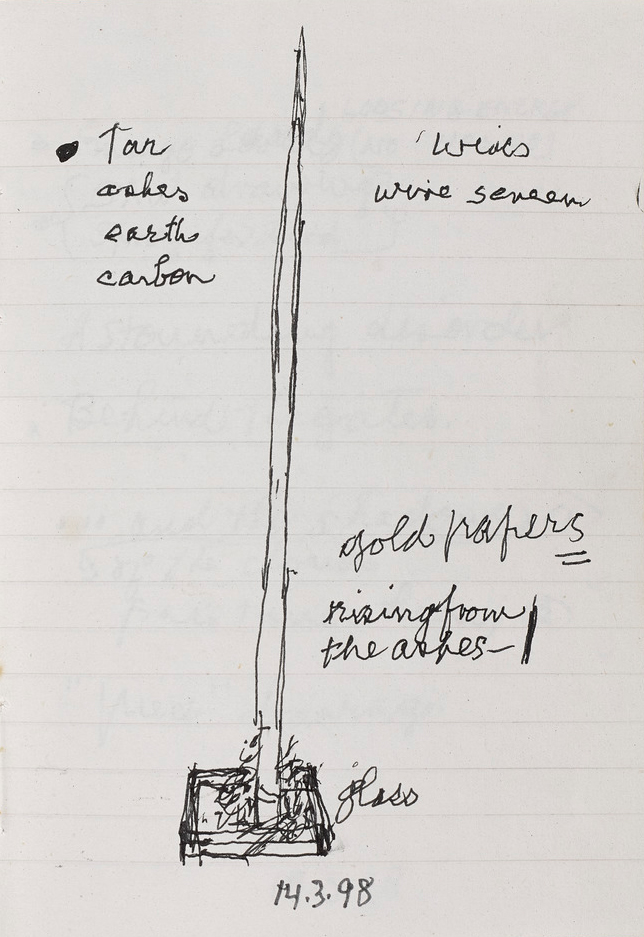

Goodwin also used wire, plaster, and steel rods to make independent, ethereal spinal forms in the early 1990s, as in Spine, 1994. In these spare white sculptures, the vestigial presence of the body is realized as a delicate, vulnerable form, yet one that Goodwin extracts as the nerve centre of the body. Spine surpasses anatomical description to become instead a simple, javelin-like vertical form bristling with wires. Without the body, it stands alone, a measure of existence that restates the common paradox in Goodwin’s work of life force and fragility. Characteristically, the idea of the spinal column existed in rudimentary sketches in Goodwin’s notebooks decades before it resonated with her again.

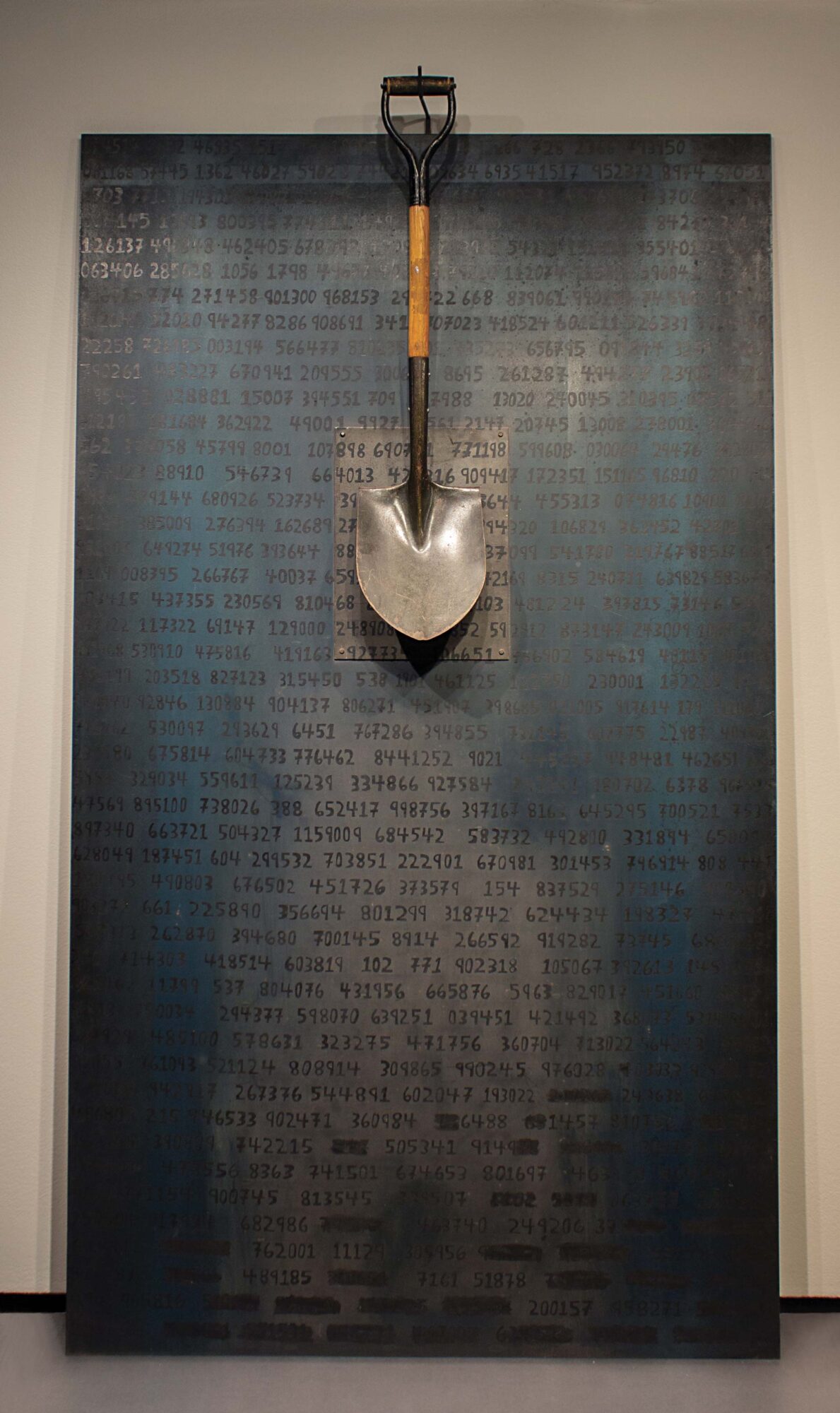

As was her habit, an accumulation of events rather than a single incident was more often the impetus for Goodwin’s work. The great collective trauma of the Holocaust surfaces indirectly in her oeuvre. Goodwin did not present herself as a Jewish artist, and without doubt the mounting numbers of deaths due to AIDS, too, weighed equally upon her. Yet over the years she copied many phrases from Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi, whose writings address the Holocaust specifically, in her notebooks. Levi’s phrase “to erase great clusters of reality” appears among these, and in 1996 she saved a feature article from the New York Times Magazine entitled “The Holocaust Was No Secret.” Her most direct allusion to this abominable trauma and loss is found in her 1995 work Distorted Events, where a large steel plate is completely covered with sequences of numbers, an unmistakeable reference to those tattooed on the arms of concentration camp inmates. It leans against the wall, an ominous shovel suspended in front of it. The dark message of this work is reiterated in the hollow phrase scratched on one of the small steel plaques from her 1988–89 Steel Notes series: “everything is already counted.”

In her life, as in her art, Goodwin grappled with the vicissitudes of adverse events. In May 1990, she wrote in her notebook in capitals “DISCIPLINE PATIENCE ENERGY,” exhorting herself, sometimes addressing herself with her given name, Béla. She repeated those words several times over the years to keep moving forward with her work no matter the obstacles she experienced, or doldrums she endured in her creative process. The theme of time preoccupied her, especially in its relationship to loss. It emerges in her installations in abandoned spaces, and most explicitly in Pulse of a Room, 1995. Here, three huge pendulums represent the passage of minutes and hours on a wall opposite two small steel room–like enclosures that evoke an eerie sense of entrapment, if not the gas chambers of concentration camps themselves.

Space & Time

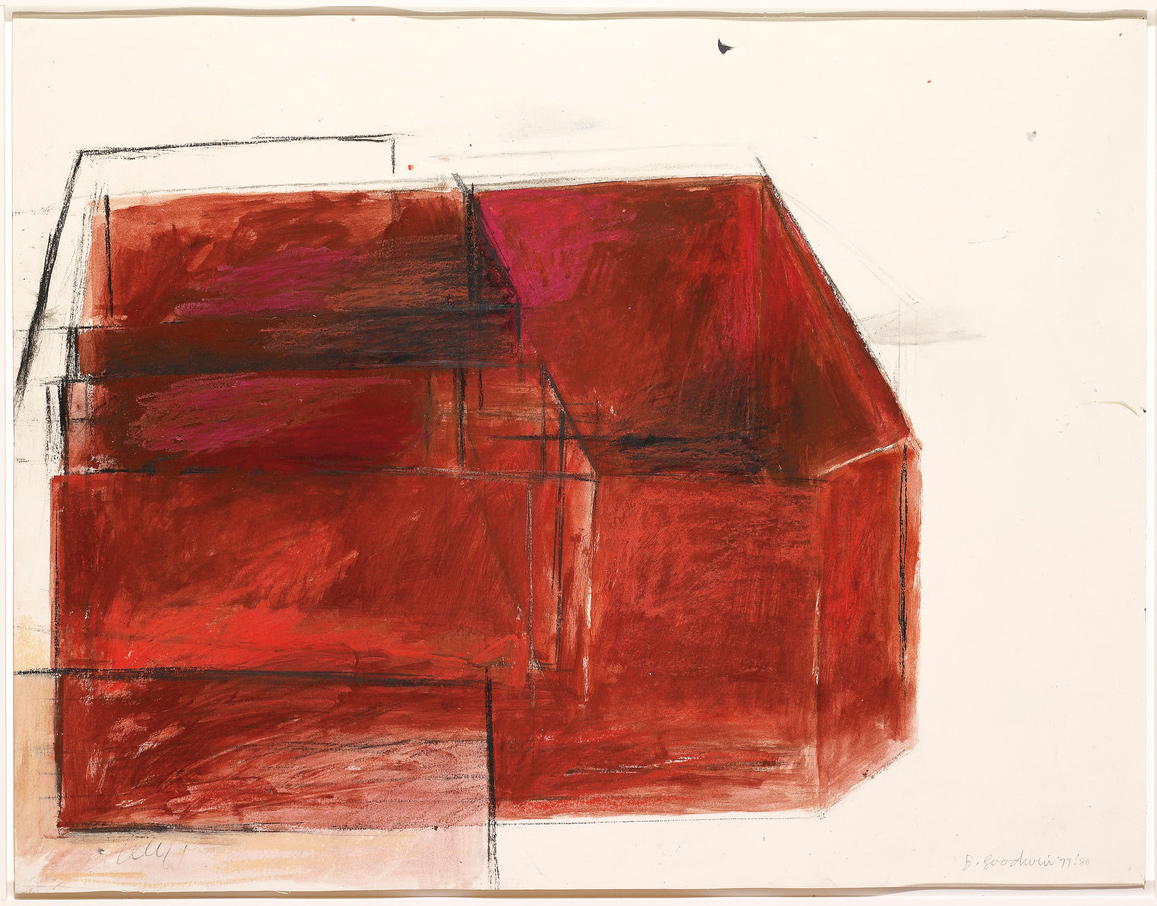

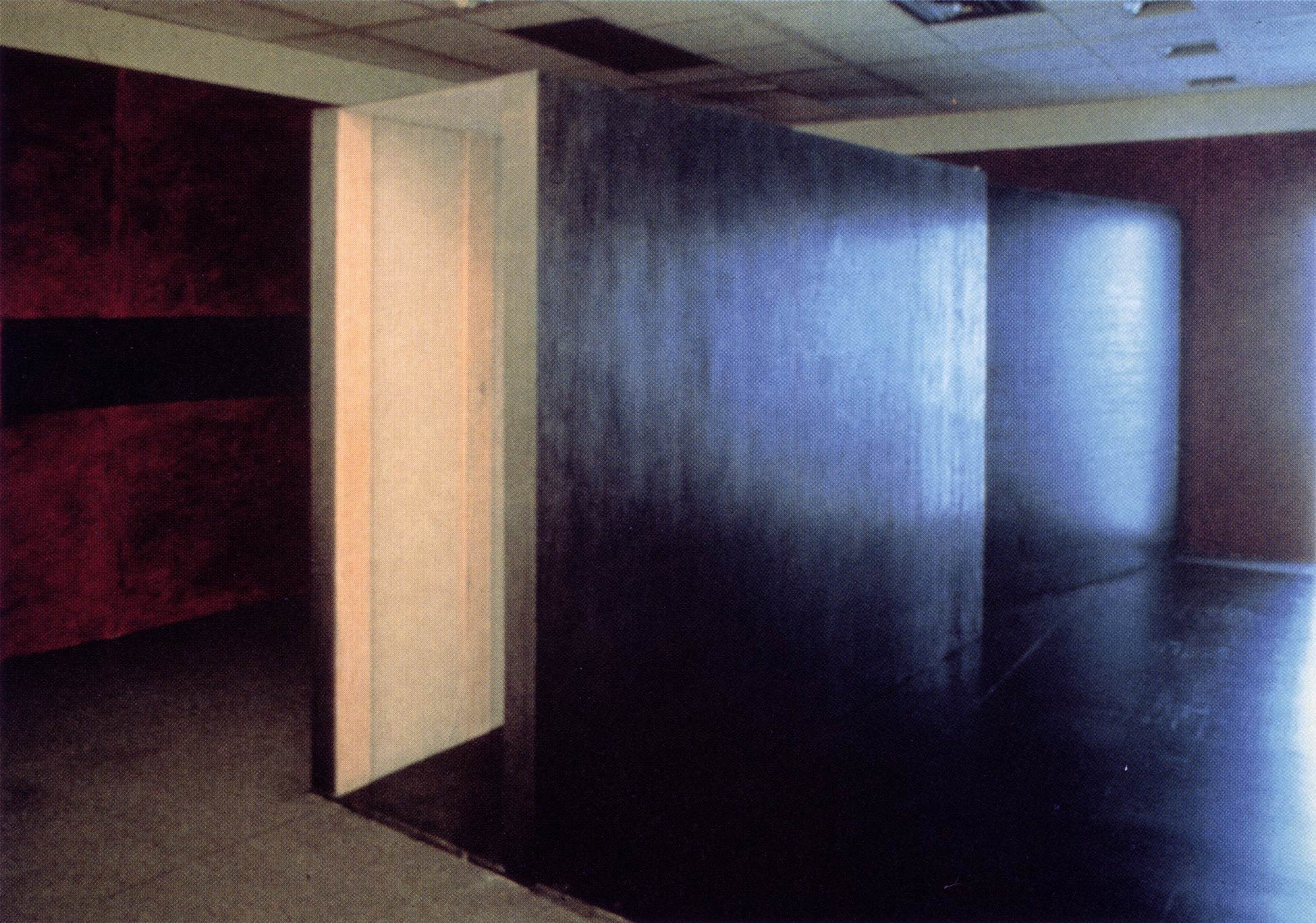

Like her peers, such as Irene Whittome (b.1942), and the duo Martha Fleming (b.1958) and Lyne Lapointe (b.1957), by the late 1970s Goodwin became attracted to spaces outside the gallery or museum and sought the greater freedom of movement, variability of scale, and variety of material approaches offered by alternative milieus. Her installation works emerged out of her attention to existing architectural elements, the quality of light, and the former uses of spaces. This reimagining and animation of space demanded a material language for which Goodwin developed her own techniques, including the construction of three-dimensional interventions in the form of passages. She performed subtle modulations of surfaces using combinations of gesso, paint, pencil, and oil pastel first explored in her tarpaulin works.

The theme of passage alluded to both communication and the inexorable progression of time—the passage of lives in installations like her Mentana Street Project, 1979, where Goodwin responded to the inherent atmosphere of abandonment in an empty domestic space. Describing this project, curator and critic Bruce Ferguson noted theorist Rosalind Krauss’s influential essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” published the same year, in which she claimed a blurring of boundaries as artists moved beyond sculpture’s traditional material limits, making works that interacted with landscape or architecture using extended trajectories and successive spaces.

Writing in 1981 about the relationship between performance art and installation art, critic and academic René Payant considered the time-based qualities these forms shared and how they required the viewer’s participation to fully exist. He claimed that Goodwin’s installation at the National Gallery of Canada, Passage in a Red Field, 1980, implicitly invited the spectator to wander around within it, noting that photographs could not capture the complete work but could only document it from several discrete positions. Describing the effect on the viewer, he stated: “those who actually ‘visited’ the installation were the only ones who could talk about it.” Payant’s close analysis of Goodwin’s work traces how in several installations made from the late 1970s through the mid-1980s, she created an experience of space that was palpable, and profoundly memorable.

In this period, the reductive self-referential forms that typified Minimalist works, and the primacy of ideas rather than their formal realization, as embodied by conceptualism, were being displaced by a pluralism of art forms. Other artists in the Montreal milieu were testing these boundaries too. Lyne Lapointe and Martha Fleming collaborated on extraordinary projects in derelict buildings, reviving socio-economic histories of such venues as a fire hall and a vaudeville-style theatre. Their Musée des Sciences, 1984, made in a former post office, presented a psychosexually charged history of the body played out in an immersive environment where several narratives, including feminist and lesbian histories and the role of science and museums in instilling gendered representations, were woven together. Goodwin’s contemporary Françoise Sullivan (b.1923), a dancer, choreographer, and visual artist who had participated in the Refus global manifesto by the Automatistes in 1948, was detaching her paintings from the stretcher, using non-traditional formats and making assemblages that traversed two- and three-dimensional space.

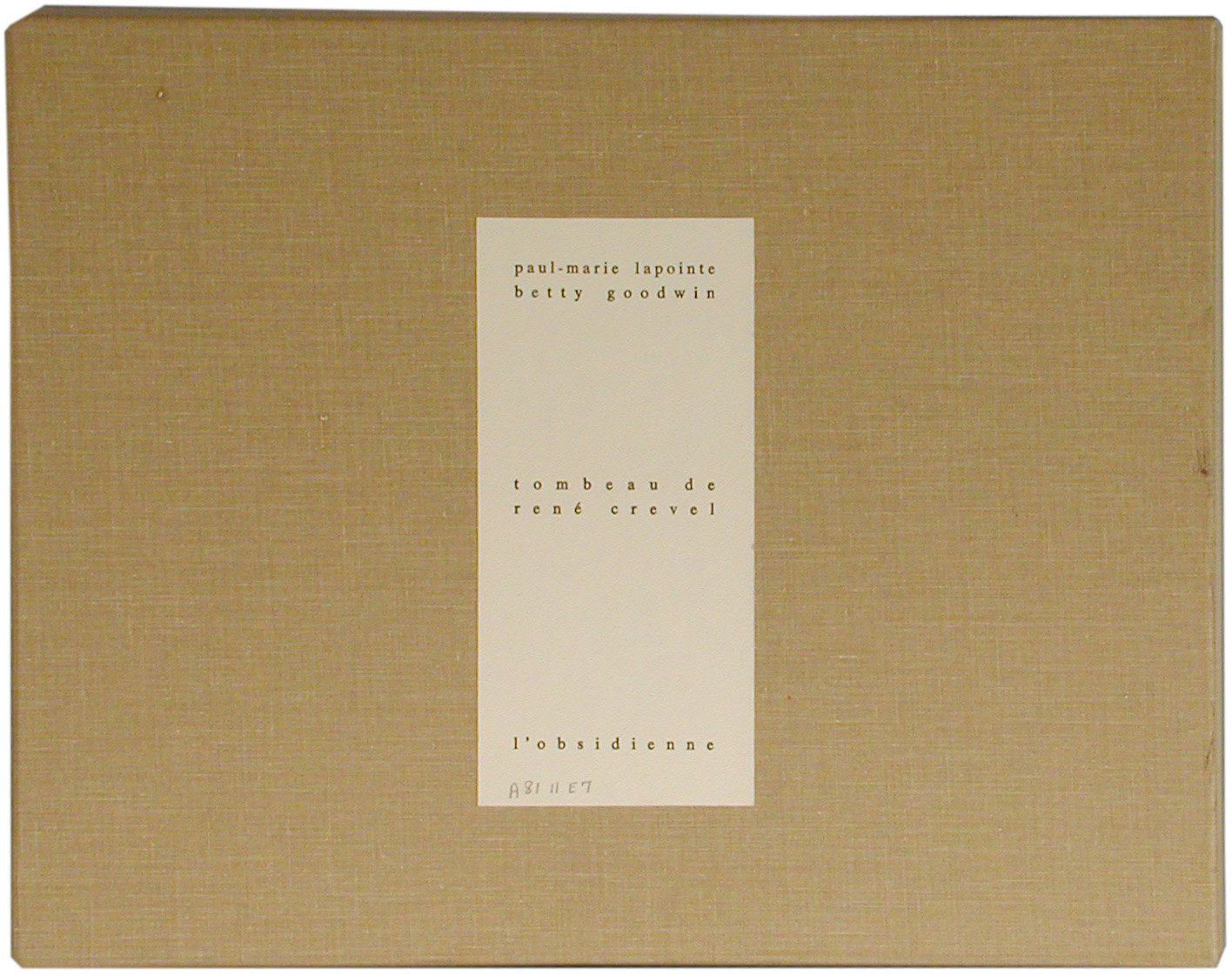

As Goodwin built a distinctive repertoire of materials and themes in her art, writers and choreographers sought her participation in several projects, signalling the impact of her work on the current interdisciplinary spirit of artistic innovation. While she was working on The Mentana Street Project, painter Guido Molinari (1933–2004) suggested to Goodwin that she collaborate with writer Paul-Marie Lapointe (1929–2011) on an edition of poems he had written as a tribute to French surrealist writer René Crevel (1900–1935). For this edition of Tombeau de René Crevel (Tomb of René Crevel) (1979), Goodwin contributed seven etchings based on the floor plan of the Mentana Street apartment. Prior to starting The Mentana Street Project, she had photographed funerary monuments during her travels. The pronounced theme of the tomb in her observations provided a connection to the Crevel poetry edition project, in which the word “tombeau” doubles in French to mean both tomb and a tribute in the form of a poetic or musical composition.

In 1992, dancer and choreographer Paul-André Fortier (b.1948), who also worked with Françoise Sullivan, was inspired by Goodwin’s art to collaborate with her on his solo performance Bras de plomb, 1993. Goodwin created both the stage set and a pair of lead arms worn by the dancer, which extended his arms toward the floor and weighed them down with gravitational pull against the lightness of the body in motion.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements