Vest One 1969

Betty Goodwin, Vest One, August 1969

Soft-ground etching, etching, drypoint, and roulette with oil pastel and graphite on wove paper, 70.7 x 56 cm (overall), 60 x 45.9 cm (plate)

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

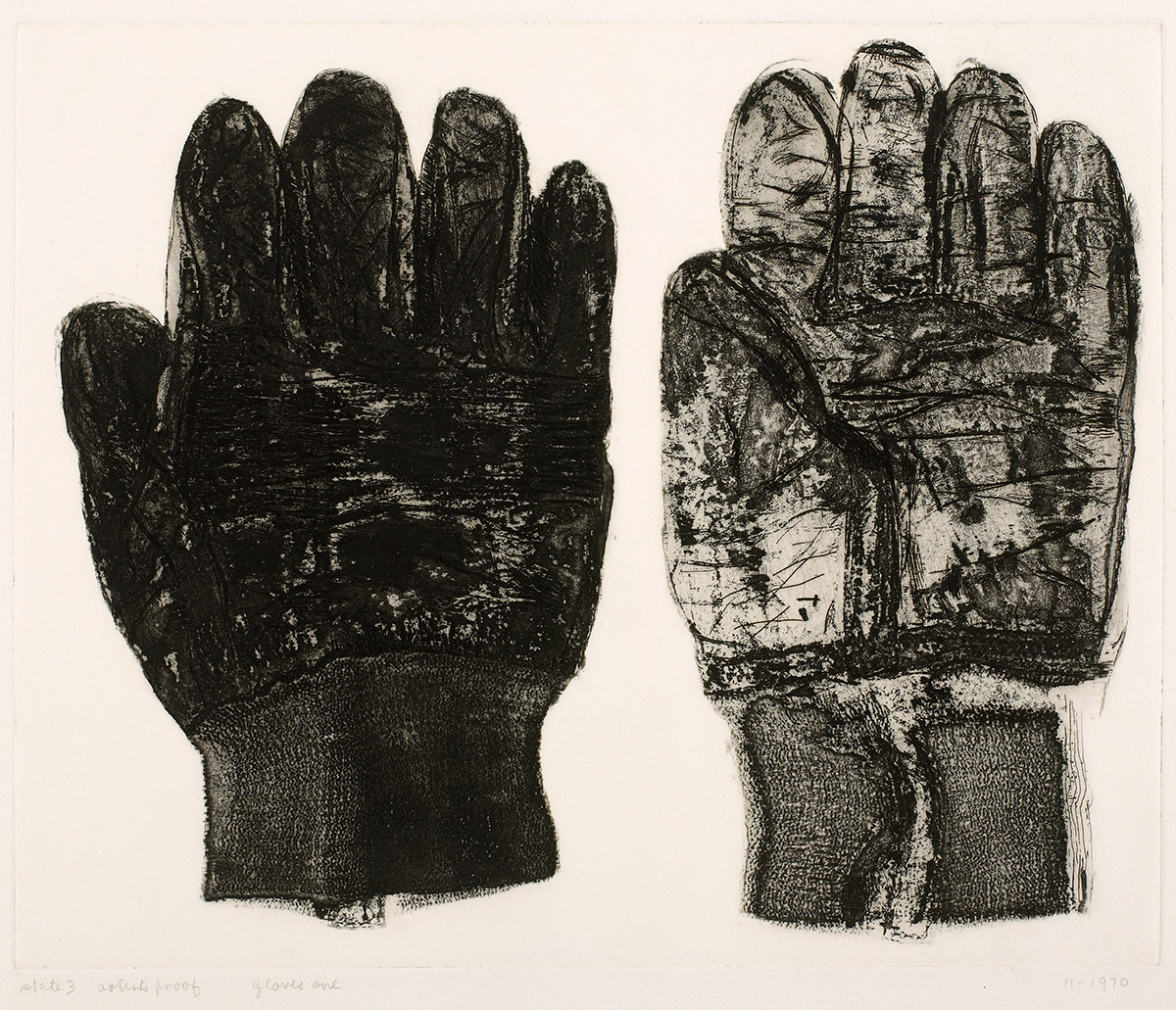

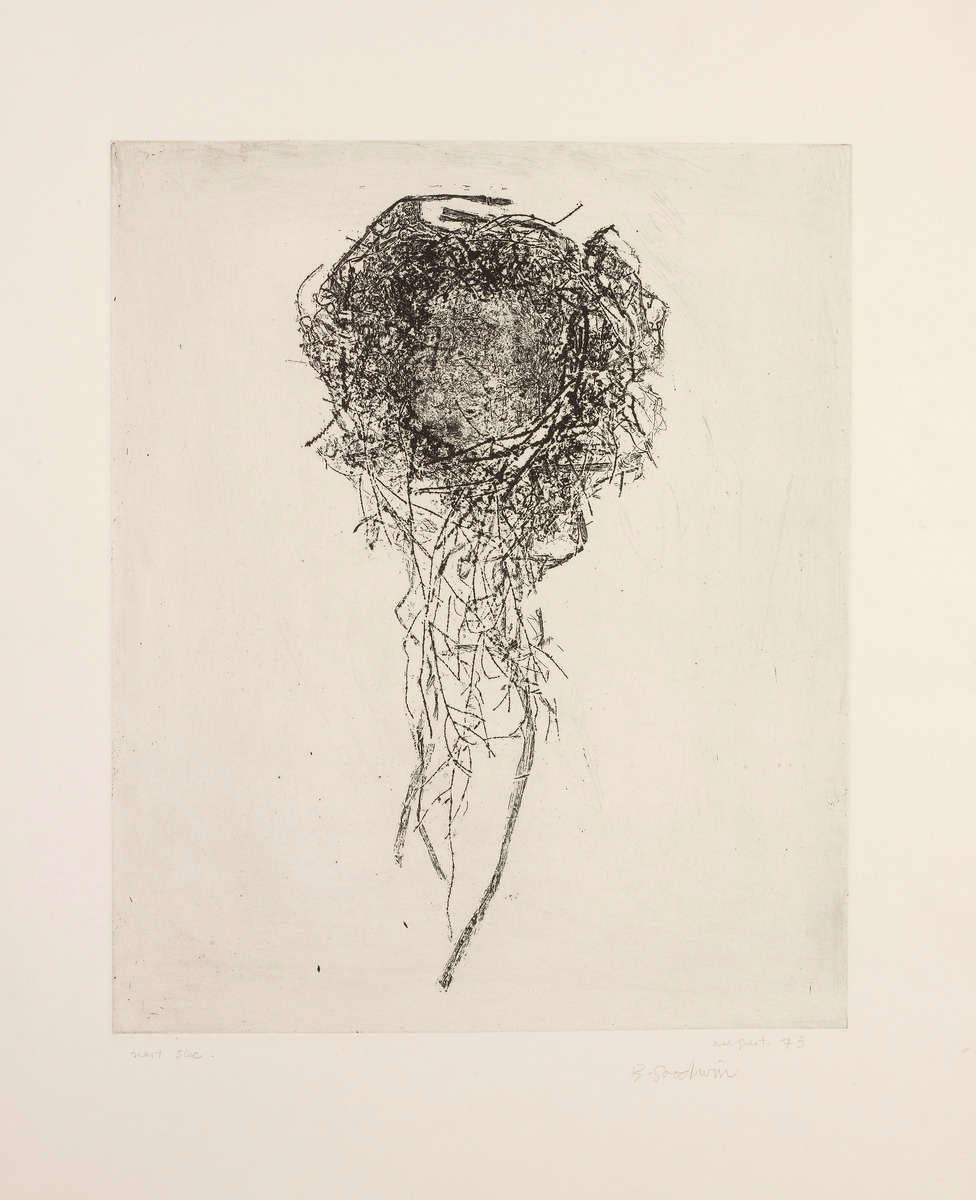

Vest One, a simple frontal imprint of a man’s vest, is the iconic image that set Betty Goodwin’s career in motion, propelling her to become one of Canada’s most celebrated artists. Goodwin had been making art for two decades, and she experimented with printmaking, working on a small press in a self-taught manner, until a printmaking class at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University) in the late 1960s introduced her to soft-ground etching and led to a breakthrough in her work. The process produced a detailed two-dimensional replica of the original object. Goodwin, enthralled by the resulting directness of the image, immediately recognized the technique’s potential. She began by making prints of her own work gloves. Among the many other objects Goodwin put through the press were drink cans and bottle tops collected on the street, as well as hats, shirts, parcels, and birds’ nests.

When she put a man’s vest through the press, the resulting ghostly image recalled the childhood trauma of losing her father, a vest maker. The vest “was related to experiences that had been submerged,” she said. “It was something I totally identify with, totally,… the starting point for everything else.” There is also a page within Goodwin’s notebooks that includes the quote “a lost parent is a like a lost bridge between the child and the outside world.”

The series of vest prints that preoccupied Goodwin over more than three years were the first works she understood as being meaningful and entirely her own. Importantly, she recognized that they carried layers of meaning, independent of her biography. Unable to leave this image until she had exhausted its potential, she made several versions, eventually elaborating her prints with other materials, including paint, graphite, and collage.

The vest prints received enthusiastic critical recognition. Writing in the Montreal Star when Goodwin first showed the vests in March 1970, Arthur Bardo commented, “Betty Goodwin’s recent graphics on display at the Galerie 1640 betray some of the freshest thinking seen around town this season. These are not as drawing would be, a translation of shallow three-dimensional forms into a two-dimensional code. They are instead the expression of the formal possibilities created by compressing that shallow space.” Her prints captured the texture of every thread and the suppleness of the fabric, intimately recording the garment’s life over time. Treated as emblems of life rather than life’s cast-offs, ultimately her vest images are imprints of the wearer, the absent body they once clothed. The vests freed Goodwin from the conventional approaches of depicting the figure she had worked with for over twenty years and established the theme of presence and absence of the body that persists throughout her oeuvre. The vests are commonly thought of as the true beginning of Goodwin’s artistic career, a claim she also made herself.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements