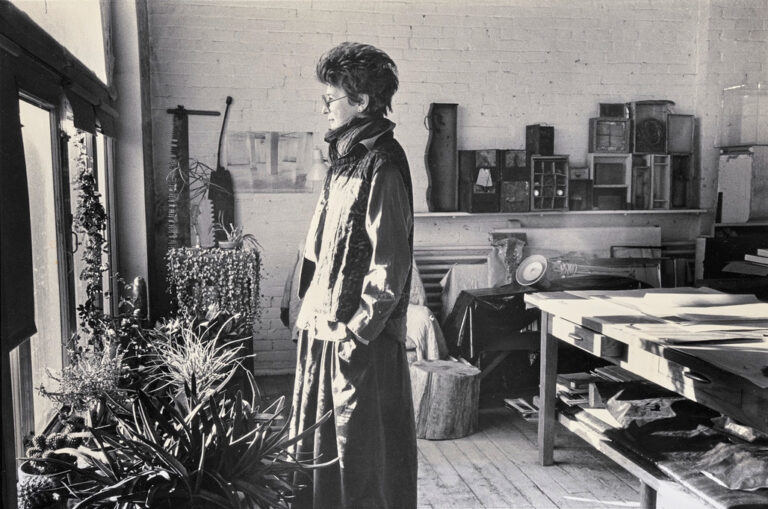

Nurtured early on by a postwar community of Jewish painters in Montreal, Betty Goodwin (1923–2008) found her artistic voice with a breakthrough in printmaking in the 1960s. Her iconic prints of vests and other objects led to installations, sculptures, and drawings that established her as one of Canada’s most celebrated artists. Goodwin’s idiosyncratic use of materials and found objects in works exploring deeply personal and political themes placed her in a cohort of artists upending traditional canons of art. With her flame-red hair and uniform of long black culottes and quilted vest, she became a beacon of singular resolve and vision in the Montreal art scene of the early 1970s and for the next thirty years.

Early Years

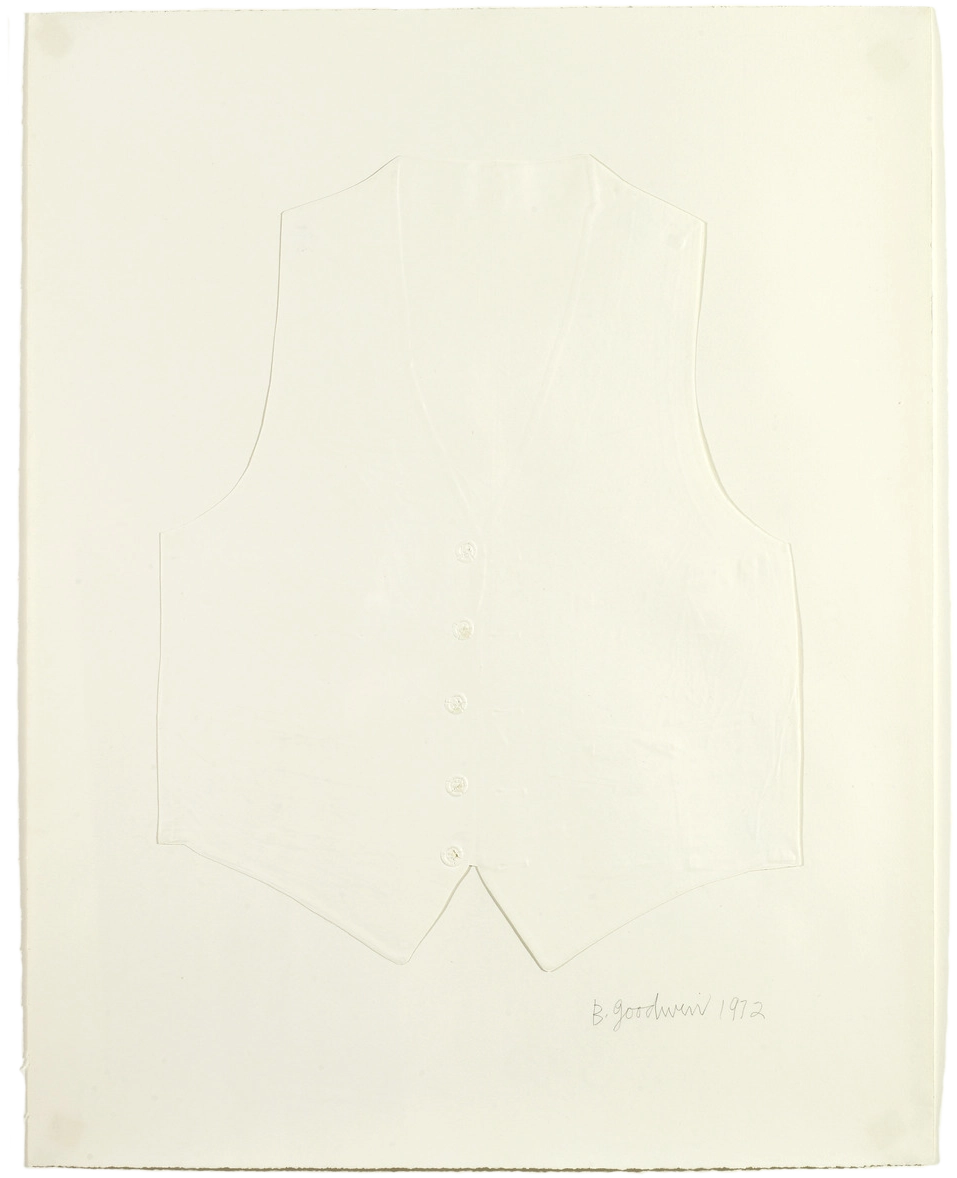

Betty Goodwin was born in Montreal on March 19, 1923, the only child of Abraham and Clare Roodish (Rudich). They came to Canada from the United States, where Goodwin’s Romanian grandparents had settled with a generation of East European Jews. Abraham, a Romanian-born tailor, could not find work in the United States. With the assistance of a relative in Montreal, he was able to join the growing clothing business there and established Rochester Vest Manufacturing Company Ltd. in 1928. The family struggled financially and four years later, when Goodwin was nine years old, her anxious childhood was marked indelibly by her father’s untimely death when he left for work one morning, suffered a massive heart attack and never returned. This trauma haunted her throughout her life and was to be followed by other premature losses of loved ones. The family was poor, though prior to his passing, Abraham had begun to expand his business. His wife took over management of the company under these difficult conditions, while the Great Depression plunged her and her daughter further into straitened economic circumstances. Goodwin later recalled: “The landlord came and took the furniture, and we had to move in with my aunt, so I guess we weren’t well off.”

Goodwin appears to have been an introverted child. By her own admission, she did not take to school and mentioned on several occasions during her lifetime how she found pleasure only in the art classes. When she finished her secondary education in 1940, this generally unhappy scholastic experience led her to decide against prolonging her education at art school. Instead, she studied design at Valentine’s Commercial School of Art and was soon working as a graphic layout artist, designing boxes for Steinberg’s, a grocery store chain. Her mother, whose textile handwork and small sculptures were treasured by Goodwin, shared her interest in art and found ways to provide private lessons as encouragement.

Goodwin soon realized her interests were in fine art, though her ambitions to pursue this, rather than focus on commercial design, were interrupted in 1945, when she met and married Martin Goodwin, a civil engineer and construction contractor. Their only child, Paul, was born the following year. No matter how constrained space and time became in the early years of family life, Goodwin never stopped making art. Later, reflecting on becoming an artist, she said, “I had one thing going for me that was good—I was tenacious. I tried. The strange part is I never said, I’m going to become an artist. I just kept going and persevered.”

A Self-taught Late Starter

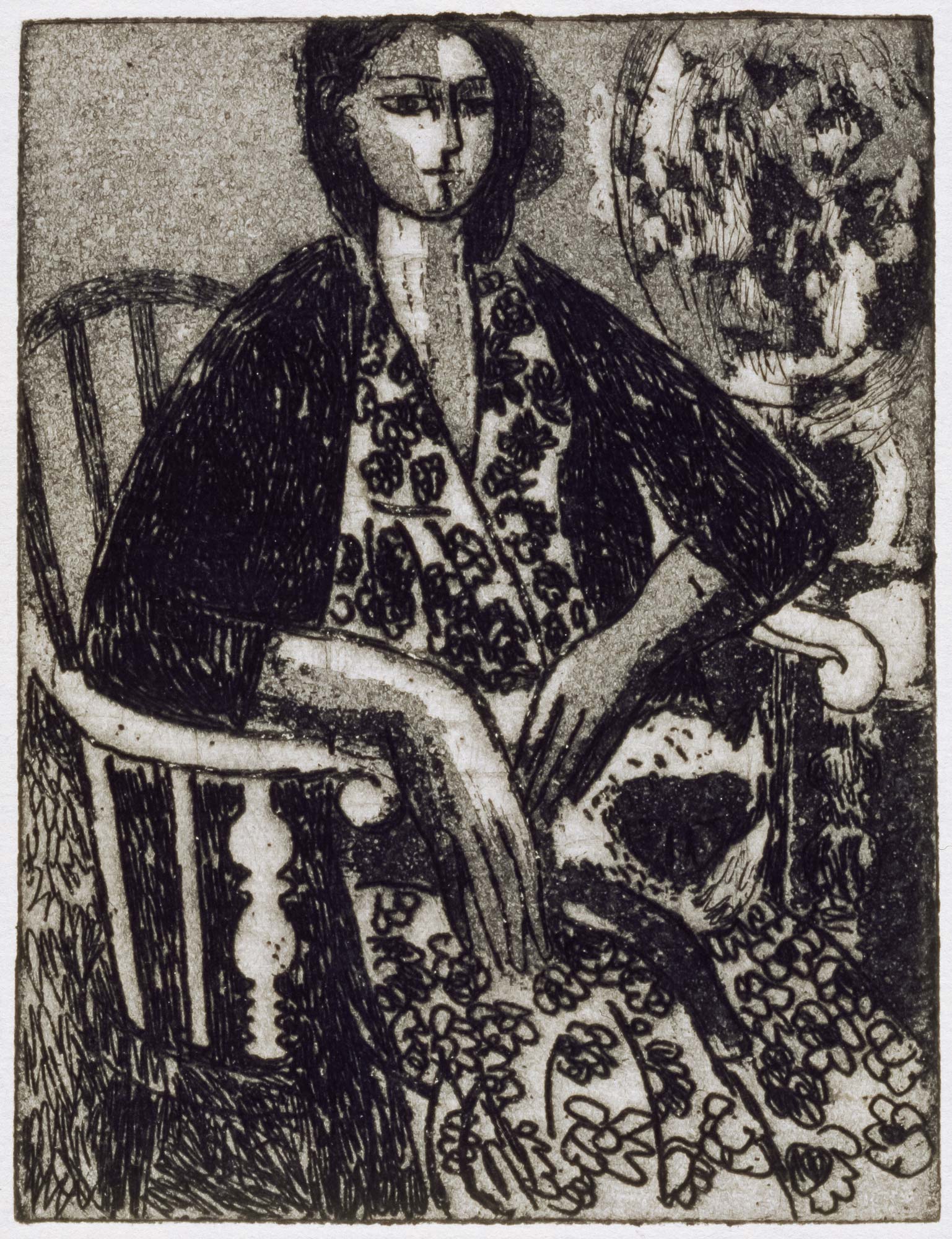

Goodwin worked at home in a solitary manner, but her artistic development was nurtured within a community of Jewish artists in Montreal whose strong sense of social justice was fuelled by postwar displacement and poverty, and the atrocities of the Holocaust. Among them were Ghitta Caiserman (1923–2005) and her husband, Alfred Pinsky (1921–1999), and Moe Reinblatt (1917–1979) and Rita Briansky (b.1925), social realist painters who were progressive advocates for change. The group, dubbed the Jewish Painters of Montreal, admired the depictions of urban life by American artist Ben Shahn (1898–1969) that focused on labour conditions and the treatment of ethnic minorities. They also drew inspiration from the work of German artist Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), whose works reflected on the human costs of the First World War and themes of social justice. They were avid collectors of Kollwitz’s etchings, which Goodwin also acquired during this period, presaging her interest in printmaking.

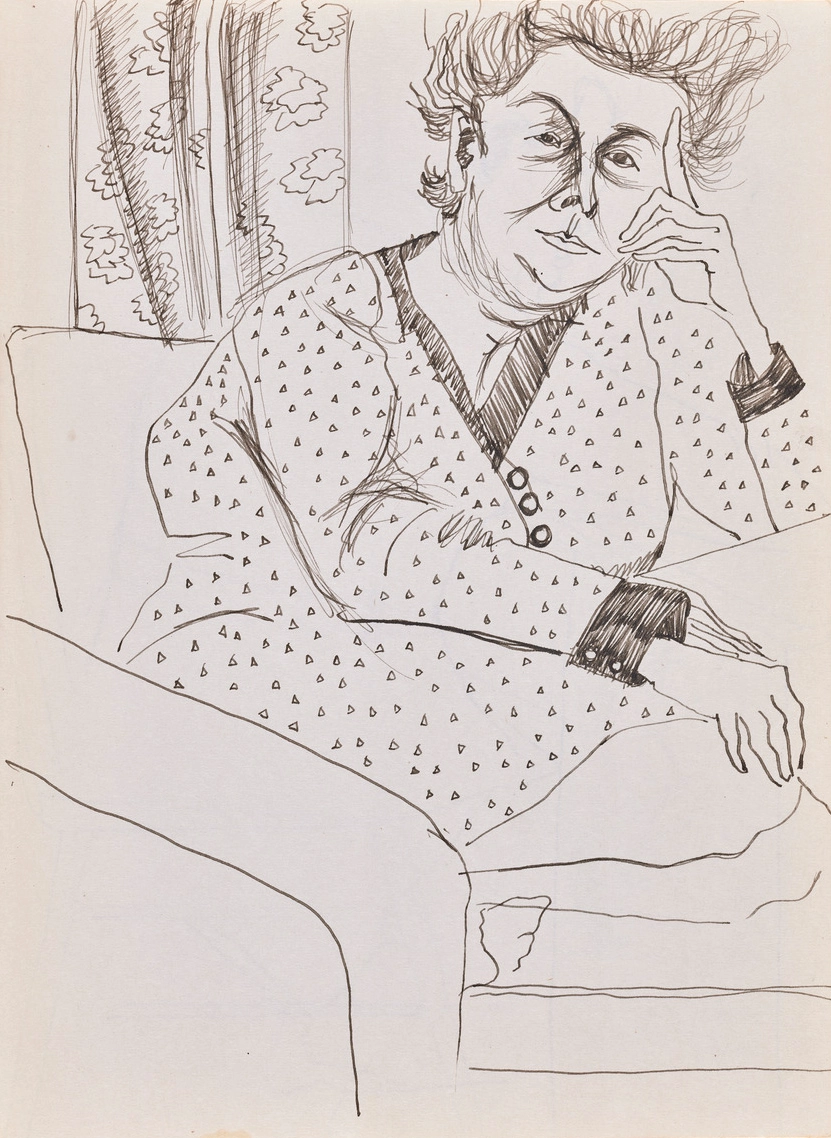

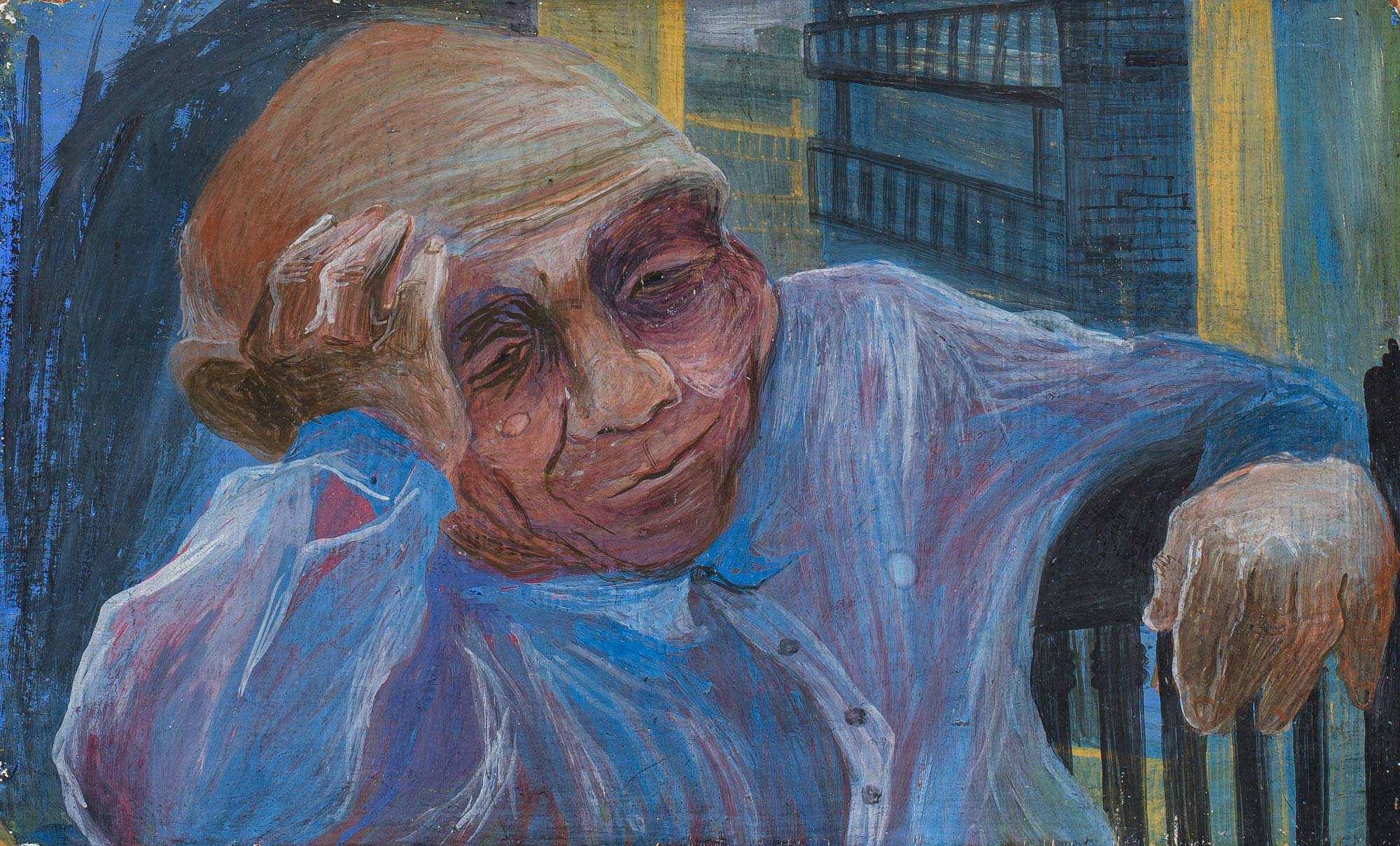

The Goodwins socialized in a wider circle of artists that included John Ivor Smith (1927–2004), Anne Kahane (1924–2023), Philip Surrey (1910–1990), and poet Irving Layton (1912–2006). Goodwin painted and drew conventional still lifes, cityscapes, interiors, and the figure, including View from my back window, 1947, and Portrait, 1949. Like many artists of her day, she entered popular annual exhibitions organized by local museums and artist societies. Her work was first shown at the 64th Annual Spring Exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 1947.

Goodwin’s husband supported her dedication as she committed herself to becoming a full-time artist, though Martin’s professional obligations generally determined the conditions under which she developed her art. When he was appointed to the National Research Council in 1951, the family moved to Ottawa for three years, and then to Boston, where Goodwin had a fruitful year exploring the Museum of Fine Arts. By 1958, the family moved again, this time for her work; Martin took a year’s leave and they travelled to England, France, Holland, Spain, and Italy so that she could immerse herself in historical European art that she had acquainted herself with primarily through books. They settled in Florence, where she set up a studio space in their apartment.

The year provided the stimulus Goodwin sought and the art education she lacked. Her keen first-hand observation of art by everyone from the early Renaissance masters to Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) strengthened her resolve to make more distinctive pieces. She writes: “I must become freer, metamorphize—I must create my own personal alphabet,” which became a refrain echoed in her later notes. While overseas, she wrote to Evan H. Turner (1927–2020), the director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, expressing her wish to show there on her return. Her effort was rewarded in 1961 with an exhibition at the museum, which had set aside a gallery to showcase contemporary artists.

Meanwhile, a social and cultural revolution was well under way in Quebec. In the Refus global manifesto of 1948, artists and writers in the francophone community had declared their commitment to absolute freedom of expression in opposition to the constraints of a culture dominated by the Catholic Church. Concurrently, the Automatiste movement of abstract painting was unfolding. Goodwin and her friends were aware of these developments but remained dedicated to an artistic vision more sympathetic to the humanist tradition.

By the mid-1960s, Goodwin was making colourful paintings depicting simplified figures floating, devoid of backgrounds, as in Falling Figure, 1965. She reduced the body to its basic contours in these images that were early indications of the direction she would eventually take in more intensely evocative forms of figuration. However, Goodwin was relentlessly self-critical and remained unsatisfied with her early work, much of which she is known to have destroyed. In time, she drifted away from the group of Montreal artists who had initially influenced her, and only in the late 1960s did she begin to find a more personal vision, through printmaking.

Arrival of a New Voice: Printmaking

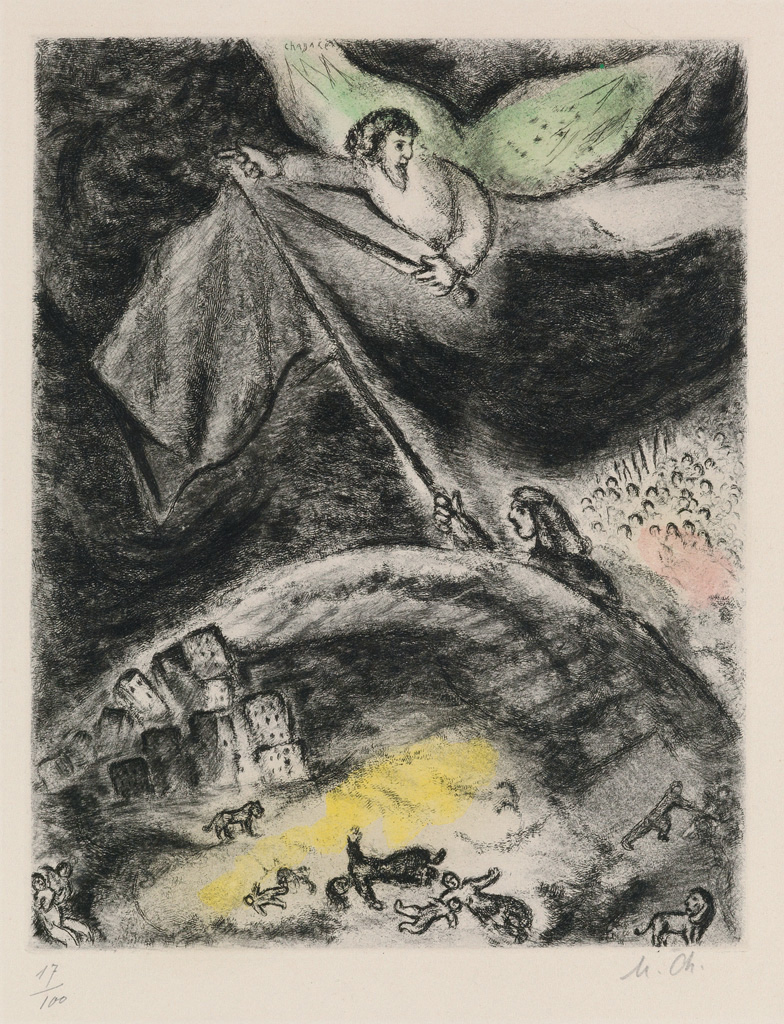

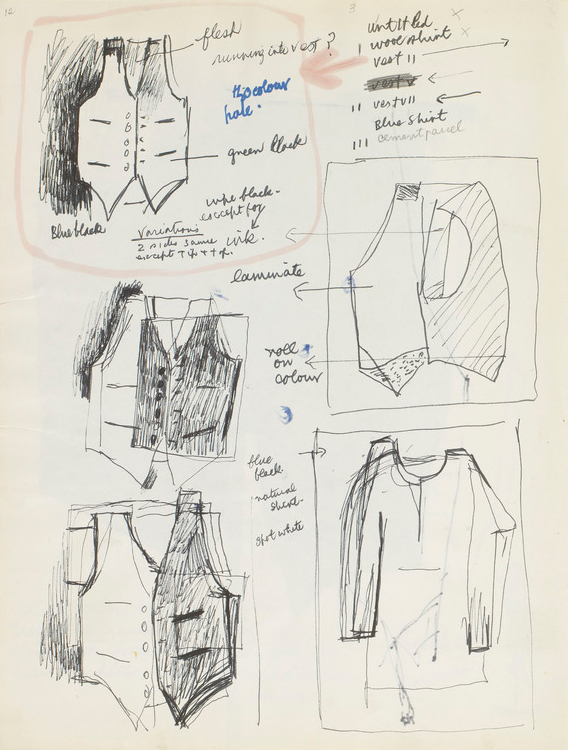

Goodwin’s notebooks in the mid-1950s reveal she was searching for technical information on etching. Like many artists at the time, her friends, including Ghitta Caiserman, were making prints. Goodwin acquired her own small press and over the next decade developed her printmaking in earnest, encouraged by her friendship with the young German Canadian artist Günter Nolte (1938–2000), whom she had met in the hairdressing salon she frequented. (Nolte worked there to support himself.) The two collaborated, exchanging information and assisting each other in their practice. Finding their way together, they read about technique and studied prints, among them those of Marc Chagall (1887–1985), Georges Rouault (1871–1958), and Pablo Picasso.

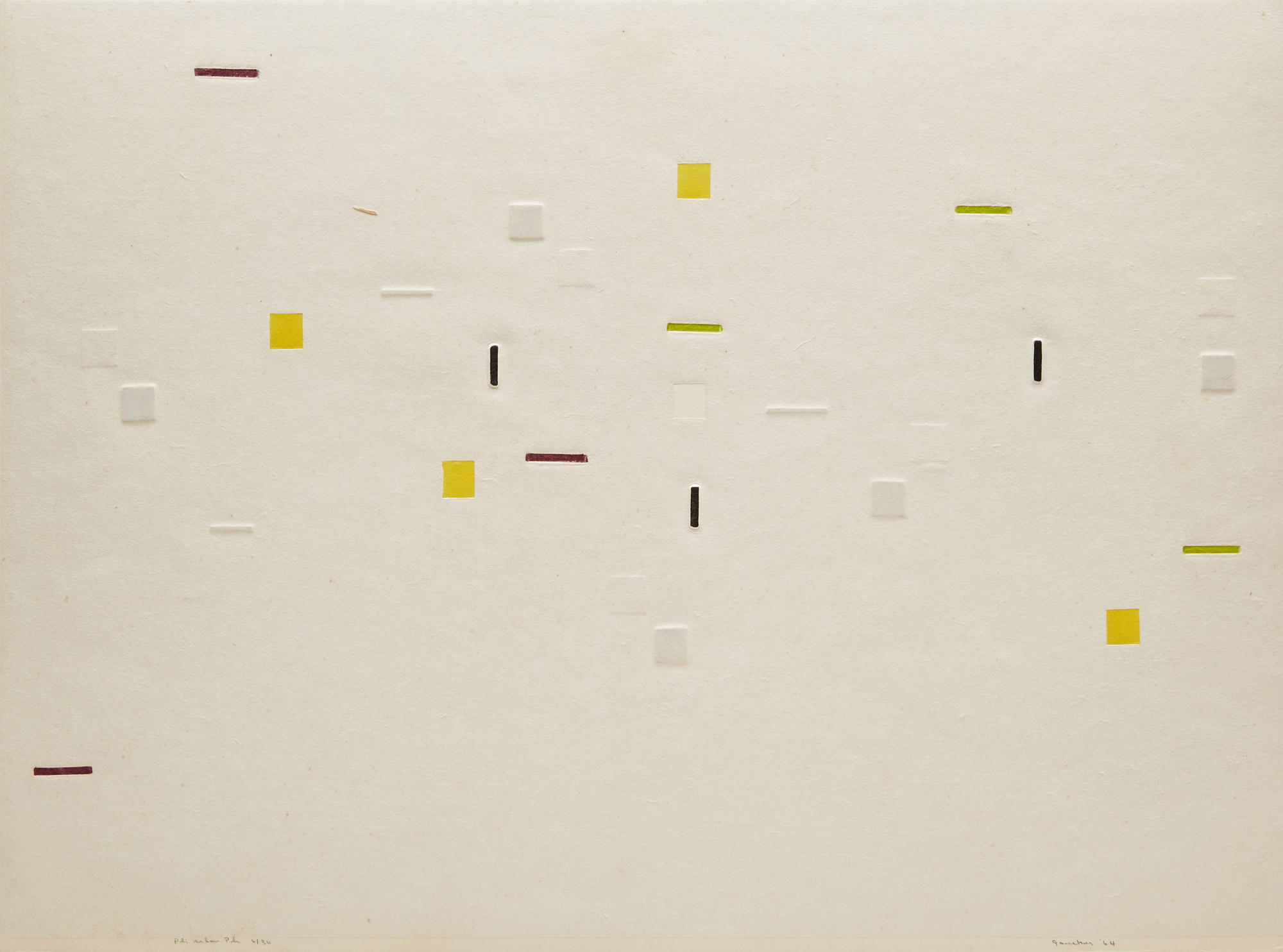

In 1965, Goodwin was elected to membership in the Canadian Society of Graphic Art, but despite this recognition, she was reaching an impasse in her work. Dissatisfied with the conventional range of subject matter and style of depiction she had been working with, Goodwin was searching for a more personal approach to her artistic expression. In 1967, she decided to reduce her practice to drawing—preferring that medium’s immediacy, its direct, more spontaneous relationship between eye and hand—until she could find her way again. A breakthrough came in 1968 when, with the recommendation of her friend John Ivor Smith, she began to attend a printmaking class taught by Yves Gaucher (1934–2000) at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University). At the time, Gaucher was the undisputed leader in printmaking in Quebec. He had studied with master printmaker Albert Dumouchel (1916–1971) and was especially renowned for his embossing techniques. Speaking of Goodwin, years later Gaucher said: “I gave her everything I could because she was the most worthy student that I had. And looking back on it she was the most worthy student I have ever had…. It’s not just the work. It’s in the attitude, the commitment, the discipline and in the earnestness if you will.”

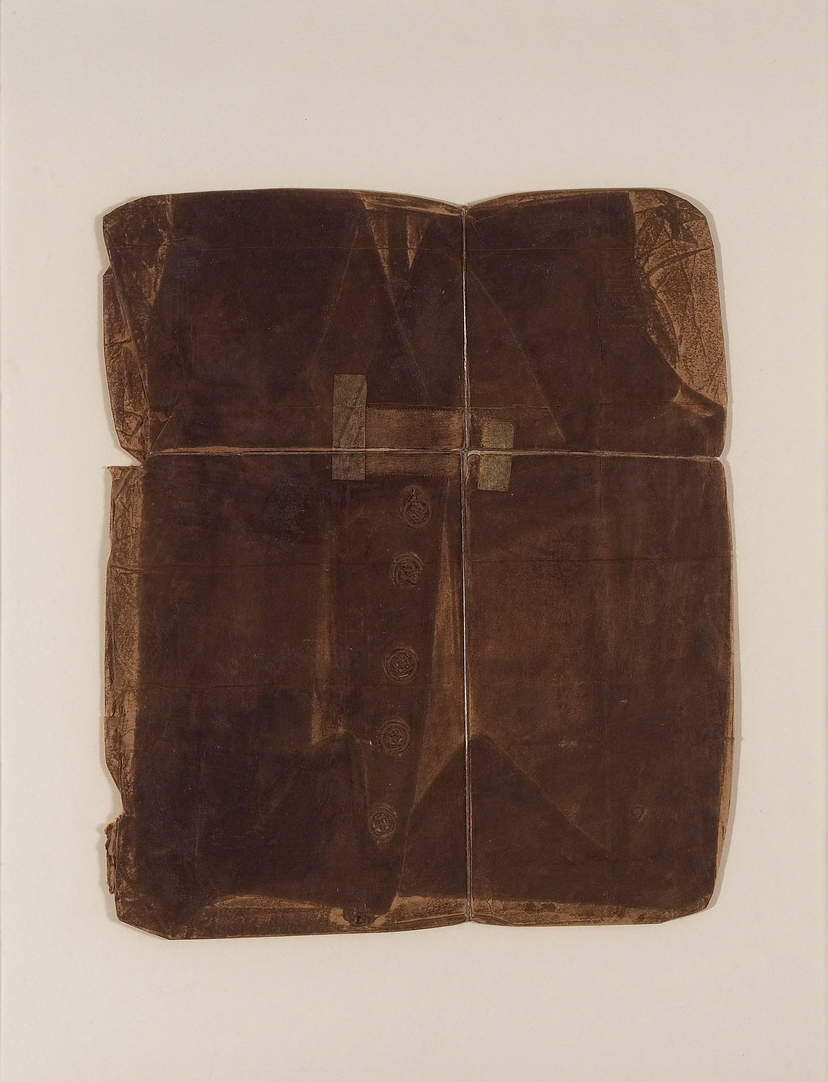

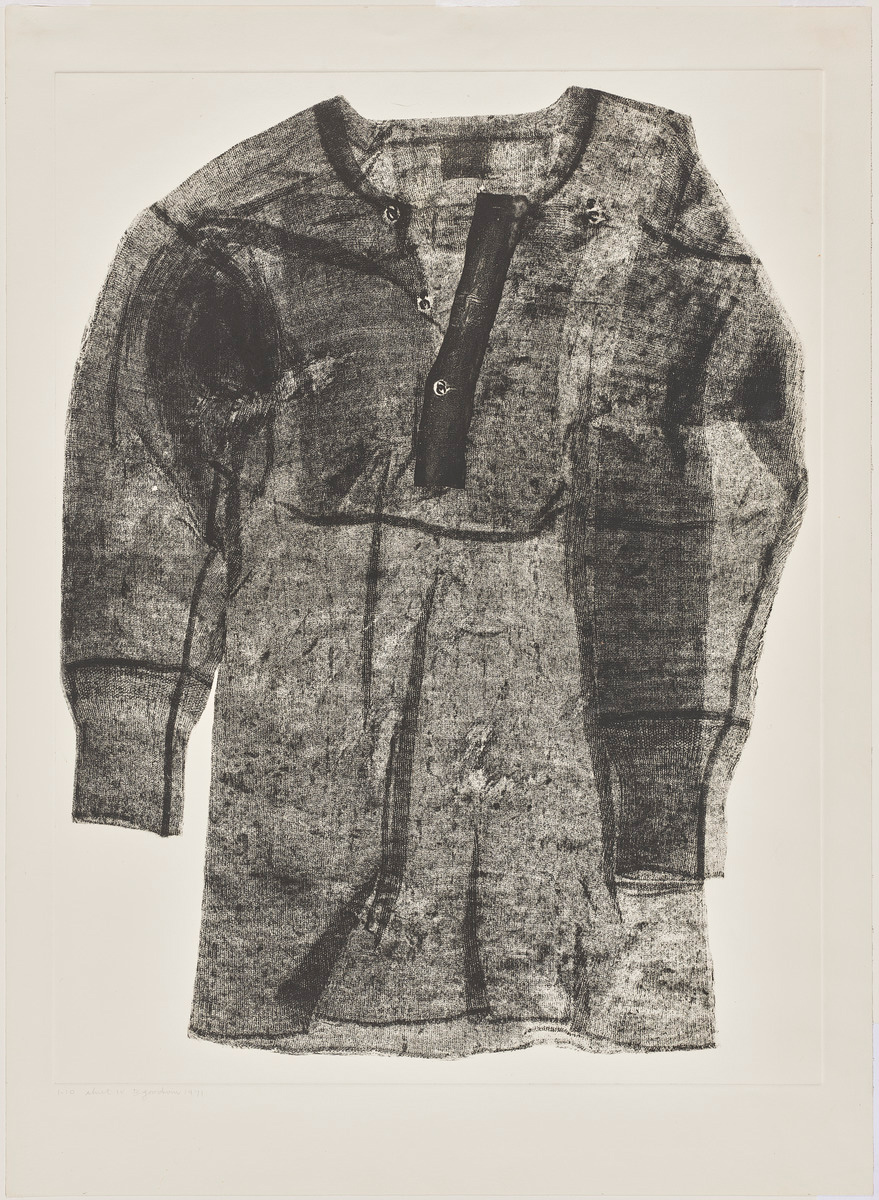

In his class, Goodwin became attracted to the soft-ground method of etching. The process, in which objects are put directly through a press and imprinted into a soft medium on the plate, then etched and printed, rendered the texture and form of ordinary objects in minute detail, bringing them to life in two dimensions. Now in her mid-forties, she profited greatly from Gaucher’s knowledge and his technical prowess, later describing the exhilaration of becoming a fine art student at this age: “It was great working in that class. Great to be a student. I liked drawing and learning about techniques. Coming there at that time in my life, I had more experiences. I learned technique but I had something I could do with it. I could make use of it for what I wanted to say.”

What Goodwin wanted to say emerged from her own past, and from deep personal loss. The faithful image of a man’s vest with its intimate connection to the body and to memories of her father, a vest maker, was to lead over the next three years to a transformative phase of her career. Goodwin had grown up seeing men’s vests in various states, from cut pattern pieces to completed garments. Their significance as emblems of life struck her forcefully when she began to handle them directly. She experimented with putting several objects and items of clothing through a press. Vests became her entrée into a new way of working, and a new place in the art world. In mid-life she had found her path, one that led to a sustained presence of the body as the repository of lived experience and, in its many iterations throughout her art, as a metaphor for the human condition.

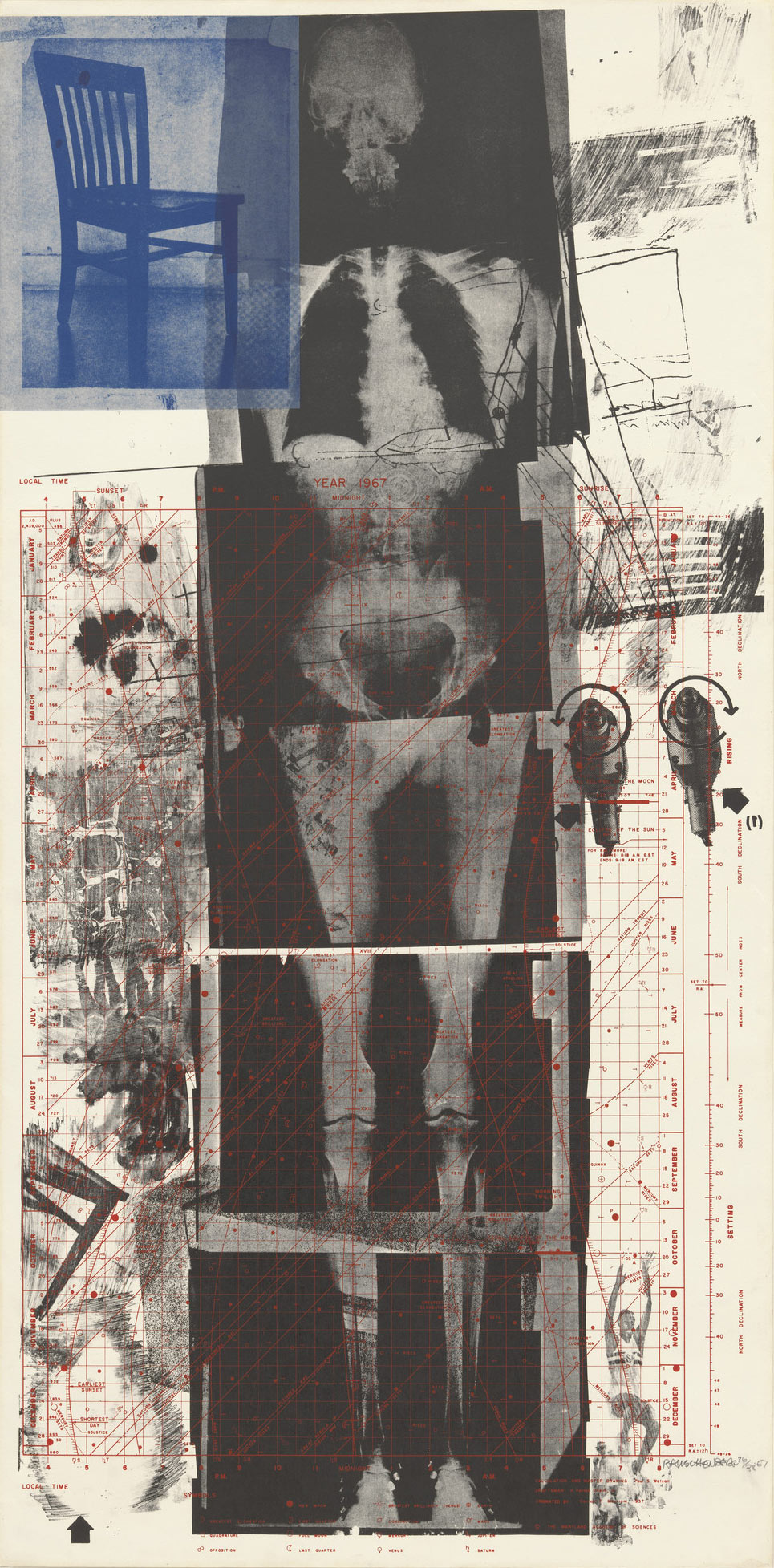

In 1970, Goodwin and her husband acquired a property in Sainte-Adèle in the nearby Laurentian Mountains, where she set up a studio that could accommodate a large press. She spent extended periods there and devoted herself to printmaking at a time when the medium was going through a renaissance internationally. Renowned American artists such as Andy Warhol (1928–1987), Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), and Jasper Johns (b.1930) had been using printmaking techniques to introduce consumer items and popular press imagery into their work. In Canada, the revival of printmaking was signalled by the proliferation of workshops across the country, such as Open Studio in Toronto and the lithography workshop at the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design in Halifax, both established in 1970. Montreal remained the most active centre for printmaking with several workshops and commercial galleries that carried prints.

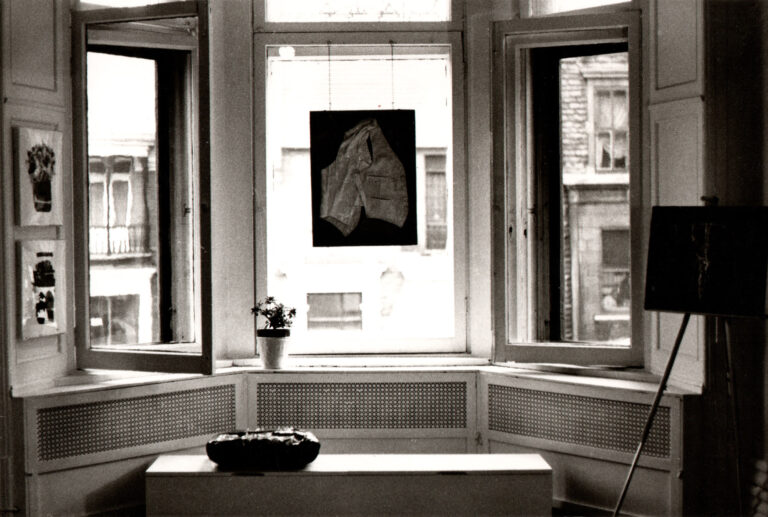

The vest prints were first shown in 1970 at Montreal’s Galerie 1640 and the next year in Toronto at Gallery Pascal. Goodwin continued to make several series of soft-ground etchings. In the fall of 1971, Roger Bellemare opened his Galerie B, establishing Montreal’s first commercial gallery to show prints by avant-garde international artists such as Christo (1935–2020), Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), and Claes Oldenburg (1929–2022). Goodwin was a frequent visitor there as well as at other galleries along Sherbrooke Street, and it was during one of her regular tours of the galleries that she met Marcel Lemyre (1948–1991), a young artist from Saskatchewan. Lemyre was an assistant at the Galerie Gilles Corbeil, next door to Galerie B, and he encouraged his friend Bellemare to look at Goodwin’s work.

Bellemare and Goodwin entered a business relationship that soon became a deep, lifelong friendship filled with discussions about art and travels together to see exhibitions. Among other affinities, Goodwin and Bellemare shared a playful love of dolls. These figured in photographs and drawings Goodwin made in the early years of a friendship she described as “une vraie rencontre,” a real meeting of minds. Conceptual art and abstraction, rather than figuration, dominated artistic developments at the time, yet with her innovative prints Goodwin was soon embraced by a younger generation of artists in a scene where experimentation prevailed, and existing definitions of art were changing.

In 1971, Goodwin received a Canada Council grant to visit the Tamarind and Gemini presses in Los Angeles, which were at the forefront of the renaissance in printmaking under way in the United States. With a recommendation from Ken Tyler, the director at Gemini, she was able to place work at the prestigious Margo Leavin Gallery in Los Angeles. Persistence continued to drive her. In New York, she met with Riva Castleman, the curator of prints at the Museum of Modern Art, where she left a vest and a shirt print for consideration. (At the time, artists could deposit their portfolios for critical appraisal.) When neither was acquired, Goodwin followed up to request another appointment. “Are you able to tell me why they were not accepted?” she inquired in her letter. While in New York, she also visited the Castelli Gallery’s graphics division, where her vest prints made enough of an impression that she received a recommendation to Blue Parrot Gallery, which carried works by such artists as David Hockney (b.1937), Jim Dine (b.1935), and Rauschenberg. Blue Parrot took some of her prints on consignment.

Goodwin was ambitious. She wanted her work to be understood in the context of the most advanced art of the time. At the Third British International Print Biennale, held in Bradford in 1972, she found the international affirmation she sought. Shirt IV, 1971, won an Arts Council of Great Britain prize. One juror, the distinguished British critic Edward Lucie-Smith, wrote, “It is only occasionally that extreme technical refinement seemed actually to serve as a springboard to something new. A conspicuous example was the print by… the Canadian artist [Betty Goodwin]. Her image of a shirt—which had apparently taken its start by making a direct image on the plate of the object itself—has haunting human presence.”

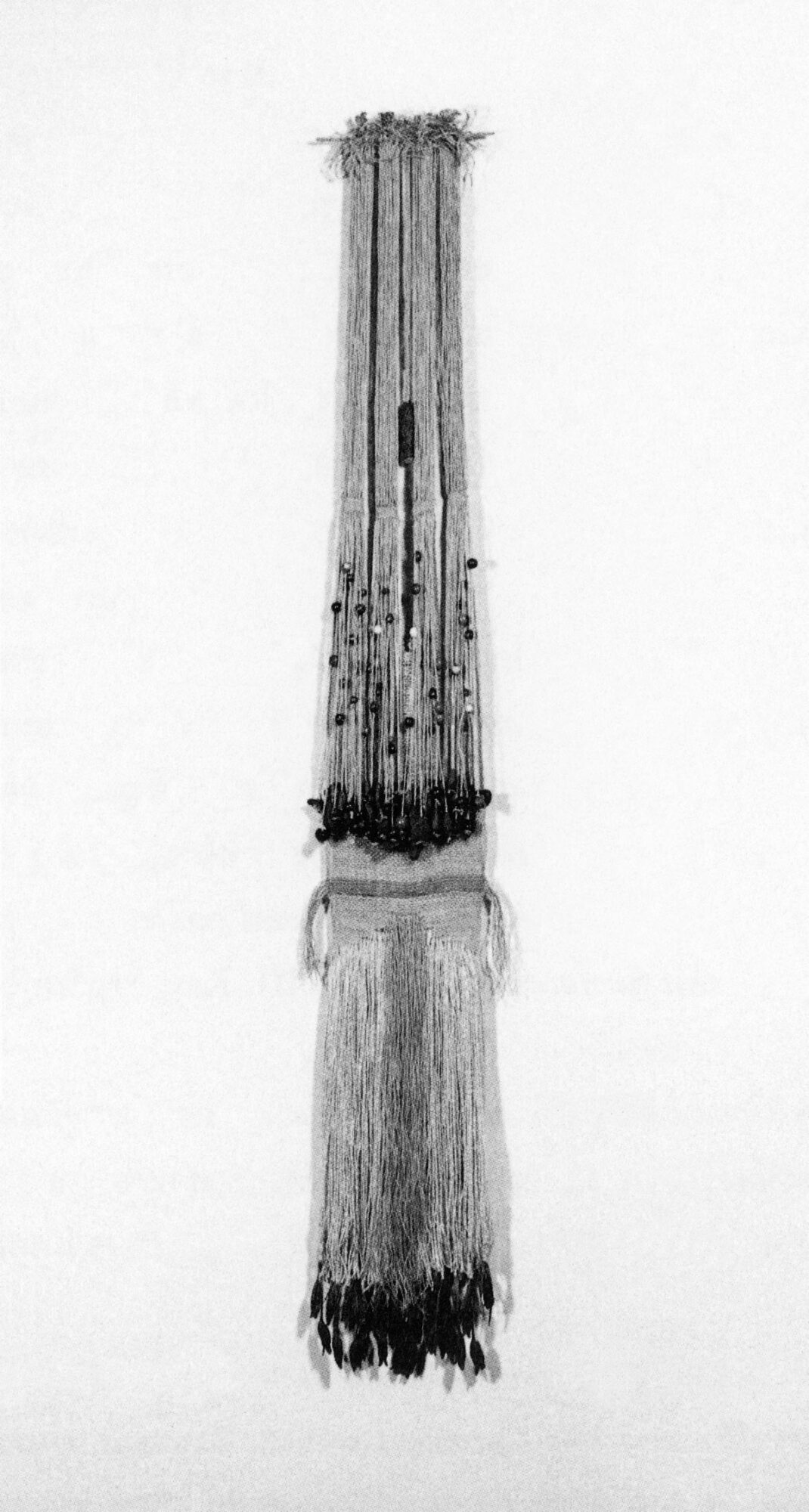

By 1973, Goodwin was exploring the vest’s material and symbolic potential further in multimedia pieces such as Vest, 1972. She was also testing the technical bounds of printmaking in her Notes series, 1973–74. Ready to leave behind the dimensional and technical constraints of printmaking, she had yet to find the impetus or the medium that would lead to the next phase of her work: “I made vests for three years,… that was enough…. However, the new image had to be as strong for me as the vests.”

Beyond the Studio: An Installation Artist Emerges

In 1974, the Goodwins rented a loft previously occupied by sculptor Henry Saxe (b.1937) and painter Milly Ristvedt (b.1942) on Montreal’s Saint-Laurent Boulevard (popularly known then as “The Main”). For the first time, Goodwin had space to stand back from her work. She continued to explore the inherent potential of found materials, venturing into larger-scale projects. For several years during walks around her Plateau Mont-Royal neighbourhood, which included a mix of residential, manufacturing, warehousing, and small businesses, Goodwin had taken photographs of the tarpaulins on transport trucks circulating in the area. She eventually acquired several when she visited the depot where they were being repaired. She was captivated by their worn appearance. Goodwin had found an object that propelled her beyond the vests into a new phase of work.

Her innovative manipulations of the tarpaulins and subtle attention to their signs of damage and repair marked a key transition in her work. She also experimented with making kite-like structures and container-like sculptures using tarpaulin pieces. At this pivotal juncture, in 1976, tragically the Goodwins lost their only child, Paul. Goodwin had watched helplessly as this reportedly brilliant and charismatic young man struggled with addiction. His death was literally unspeakable for Goodwin. Evidently, her only resource for processing this life-changing event was to immerse herself more deeply in her work.

This year of monumental loss in Goodwin’s personal life coincided with growing attention to her work and her participation in several important exhibitions, among them Cent-onze dessins du Québec, seen at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada; 17 Canadian Artists: A Protean View, organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery; and, as testimony to Goodwin’s place among younger artists forging new territory at this time, 1972–1976 Directions Montréal at Véhicule Art. The year ended with her first solo museum exhibition, at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

It is hard to imagine how Goodwin reconciled personal tragedy and these successes, which cemented her status as an artist of consequence. Then, as throughout her working life, her notebooks abounded with despair about her work’s progress, but she rarely mentioned details of her personal life, though several incomplete phrases reflect her emotional turmoil at the time. Perhaps tangentially, by way of a quote from Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966), she expressed the role her artmaking played in keeping her equilibrium: “Yes, I make pictures,” he said in the phrase she quoted, “and have always made them, ever since I was first able to draw or paint __ to attack reality, to defend myself, to nourish myself, to become stronger to be able to defend and attack.”

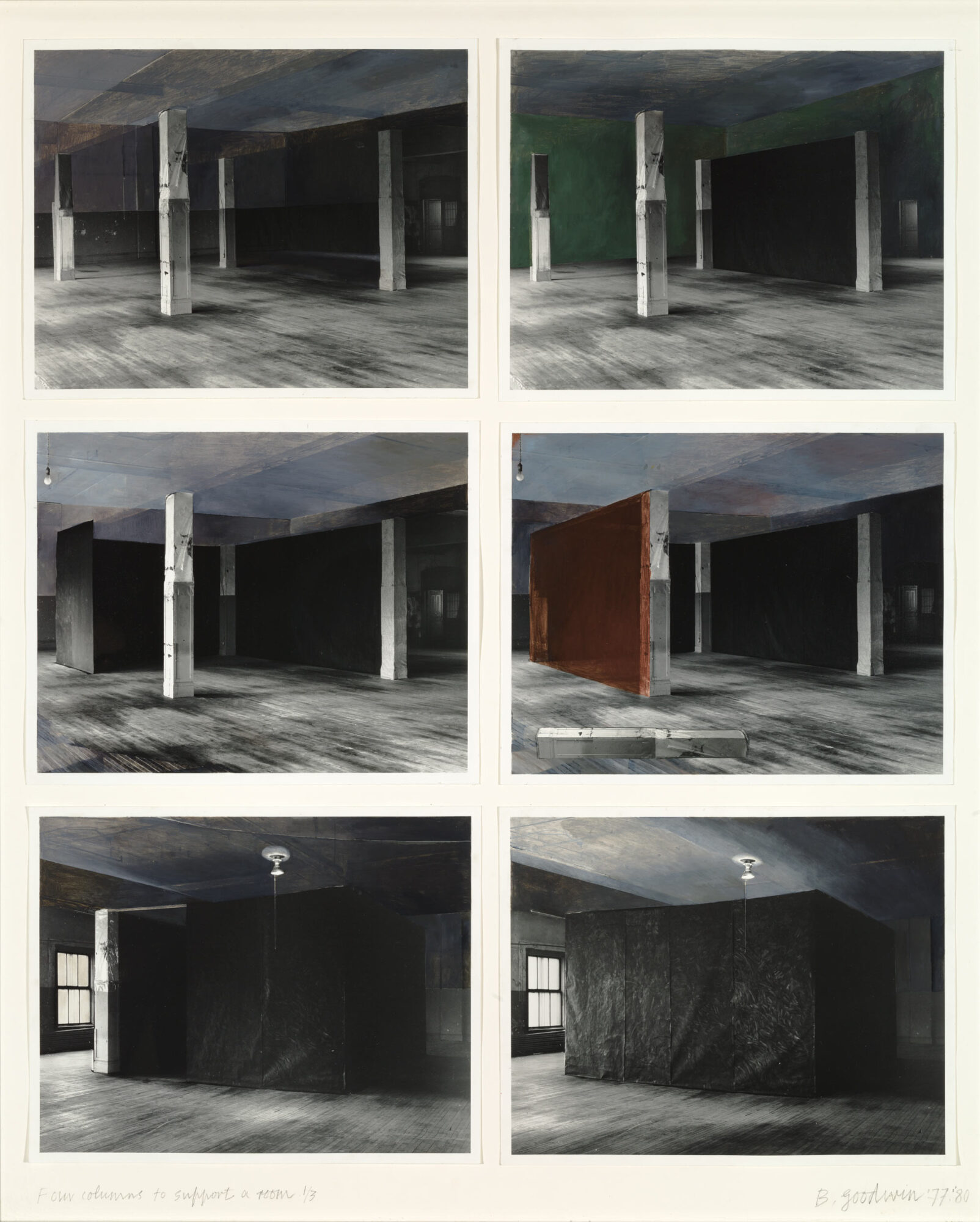

In 1977, Goodwin ventured beyond the familiarity and comfort of her studio, making a large three-dimensional piece in a disused warehouse space she rented nearby on Clark Street. The work, Four Columns to Support a Room, was a related progression from her tarpaulin pieces. In this, her first site-specific installation, she focused on the stark presence of four existing architectural columns, enclosing the rectangle they demarcated by suspending heavy black paper around the perimeter to create a room within a room. She described the sculptural form and psychological tenor of this creation as an “enormous black cube-like mass in space. Inside, the volume was very special with a totem-like piece in each corner lit by one weak lightbulb.”

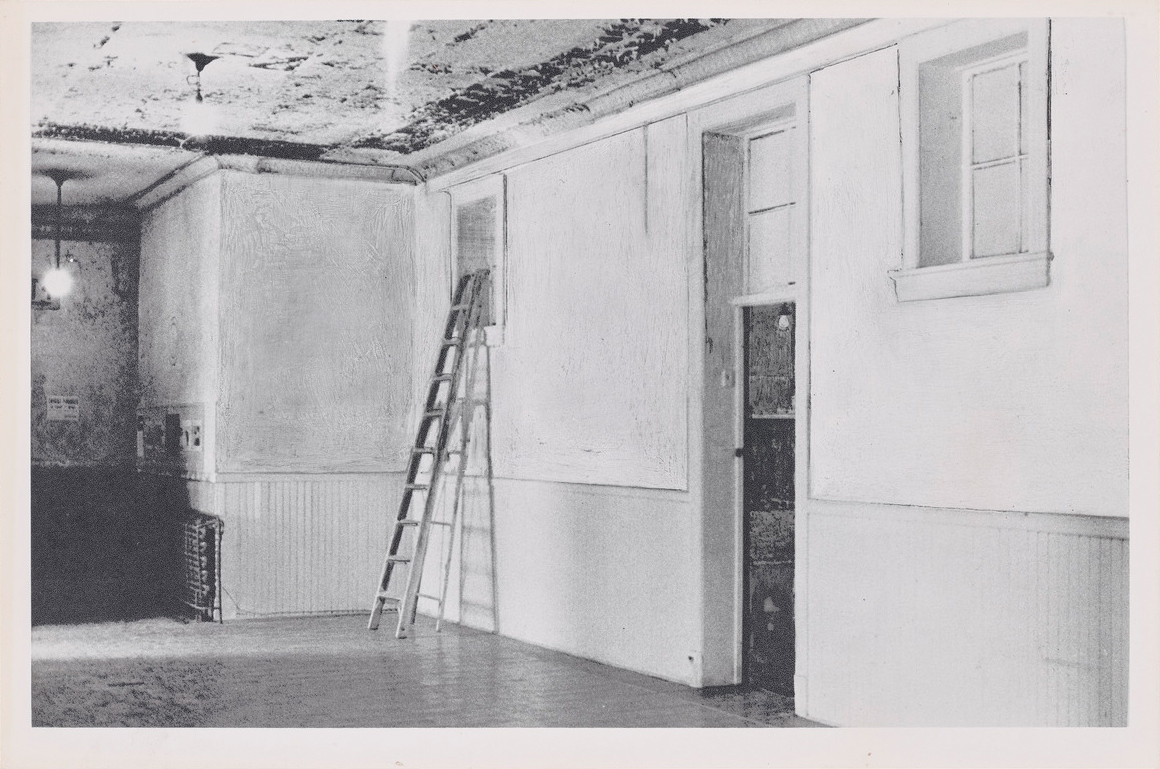

In 1979, when Goodwin was invited to make a piece for P.S.1 (now MoMA PS1)—a decommissioned public-school building in Queens, New York—she worked in a classroom. She constructed a corridor in the hallway outside, which led to a ladder the spectator had to ascend, “forcing one to make the effort to see the room which itself became the work of art.” The work was titled An Altered Point of View, 1979. At the same time, she had set her sights on the empty ground-floor apartment of a typical east-end Montreal triplex owned by Roger Bellemare, where she transformed its rooms into a haunting metaphor for lives lived. The critical impact of The Mentana Street Project, 1979, led to a rapid succession of other major installations. Site-specific installations had become the preferred approach to artmaking for many artists. An artwork could consist of several elements, without having to fit within the boundaries of a single medium, and was determined by the space it was made for.

As was her habit, Goodwin incorporated elements of her own passages as an artist into her installations: Drawing and painting were a familiar material vocabulary she used in transforming spaces. The passages that became a signature of her installations were the subject of a large group of drawings related to River Piece, 1978, a commission completed during the same period for Artpark on the Niagara River gorge near Lewiston, New York, and the only outdoor sculpture she realized.

-

Betty Goodwin, River Bed, 1977

Pastel, graphite, charcoal, and coloured pencil on BFK Rives paper, 75.7 x 106 cm

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, Quebec City

-

Betty Goodwin, River Piece, 1978

Steel, 82 x 648 x 155 cmNational Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Installation view of River Piece at Artpark, Lewiston, New York, 1978, photograph by Betty Goodwin.

-

Betty Goodwin, Riverbed, c.1977–80

Pastel, oil, sanguine, 50 x 65 cm

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

In 1980, Goodwin was invited with artists from across the country to participate in Pluralities 1980 Pluralités, the National Gallery of Canada’s centennial celebration of Canadian contemporary art. The exhibition consisted almost entirely of multimedia installation works, which challenged the institution’s traditional role of art display and preservation. The approach was unique because it took oversight away from the museum and its curators, instead empowering installation artists to compose elements of their work in the gallery space as the exhibition was being mounted. For her installation Passage in a Red Field, Goodwin penetrated false inner walls, bringing light from the museum’s modern grid of exterior glass windows through this opening and into the interior of the gallery. She deployed steel corridor structures leading through the space, painting the walls a deep red ochre.

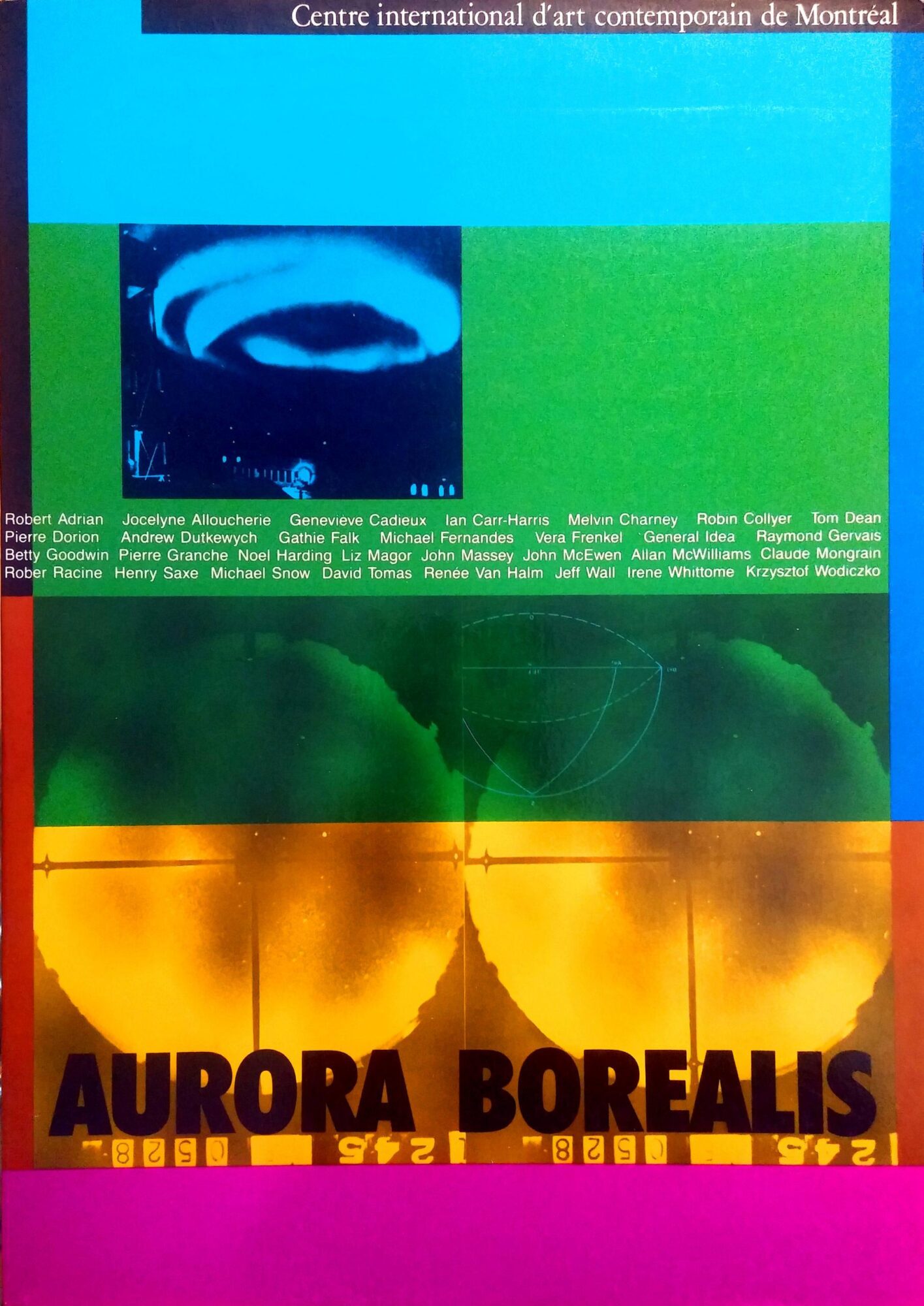

In 1982, invited to participate in another landmark exhibition, O Kanada, in Berlin, she worked again with the theme of passage to create In Berlin: A Triptych, The Beginning of the Fourth Part, 1982–83. As Goodwin completed the components of this work, she was also making drawings of swimmers, introducing the idea of the body in a struggle between sinking and surfacing. She paired the earliest of these large drawings with the Berlin sculptural installation. Then, in 1985, Goodwin introduced the figure directly into an installation, drawing on the walls in the independent exhibition Aurora Borealis, which was held in an empty underground shopping complex on Montreal’s Park Avenue.

Goodwin’s work was gathering momentum and receiving critical affirmation, and through a period during which Montreal’s burgeoning gallery scene was changing. In 1979, Roger Bellemare closed his Galerie B, and Goodwin worked without representation for a year until France Morin opened her eponymous gallery in 1981. Two years later, Morin became director of 49th Parallel in New York City, and Goodwin found herself once again without a representing gallery, just as attention to her work began to grow exponentially. In 1984, Jared Sable, who had been watching Goodwin’s work with admiration, invited her to join his Sable-Castelli Gallery in Toronto, where she showed regularly until it closed in 2005.

In 1986, Goodwin joined the gallery opened in Montreal by René Blouin, co-curator for the Aurora Borealis exhibition. Blouin became her confidant and faithful support as she worked through new phases in her mature art. Hers was the inaugural exhibition at his Saint-Catherine Street space, which became the mainstay of a vital hub of galleries that followed him into the Belgo Building. Over the next thirty years, Galerie René Blouin remained the most respected gallery of contemporary art in Montreal, recognized across the country for mounting exhibitions with international figures such as Kiki Smith (b.1954), Mona Hatoum (b.1952), and Daniel Buren (b.1938), as well as many of Canada’s most significant artists, including Jana Sterbak (b.1955), Tom Dean (b.1947), Geneviève Cadieux (b.1955), Pierre Dorion (b.1959), and Barbara Steinman (b.1950).

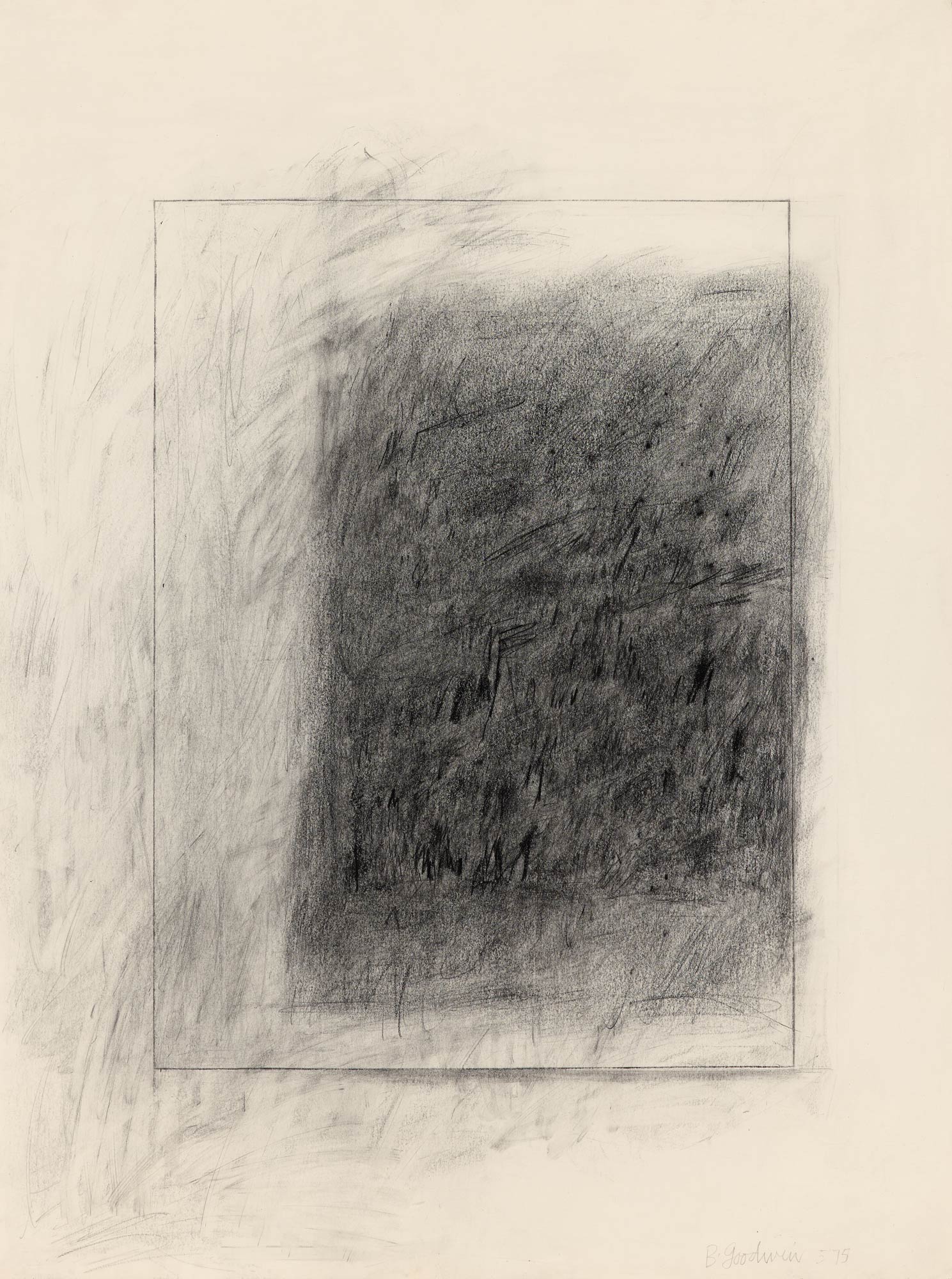

Drawing the Figure

In 1986, Goodwin became the first anglophone and the second woman to receive the Prix Paul-Émile-Borduas, Quebec’s highest honour accorded to visual artists. “It was a great joy,” she said later. “I was happy to realize that people were not concerned with the fact that I was Jewish or a woman, but that I was being rewarded for my work.” The same year, she presented Carbon, a large suite of charred black figure drawings that occupied an entire wall of Blouin’s gallery. These were an ominous precursor to the solemnity of later works, including Without Cease the Earth Faintly Trembles, 1988, as she became increasingly preoccupied with troubling worldwide events: the famine in Ethiopia, and the genocide of the Kurds in Iraq. Goodwin followed televised news assiduously at a moment when arresting images of such events began to circulate in the media with unprecedented intensity. She often acknowledged her sense of duty to know about these atrocities even if there was nothing she could do. Her “doing” was in her work, in her compulsion to address suffering and injustice through her expressive treatment of the human body.

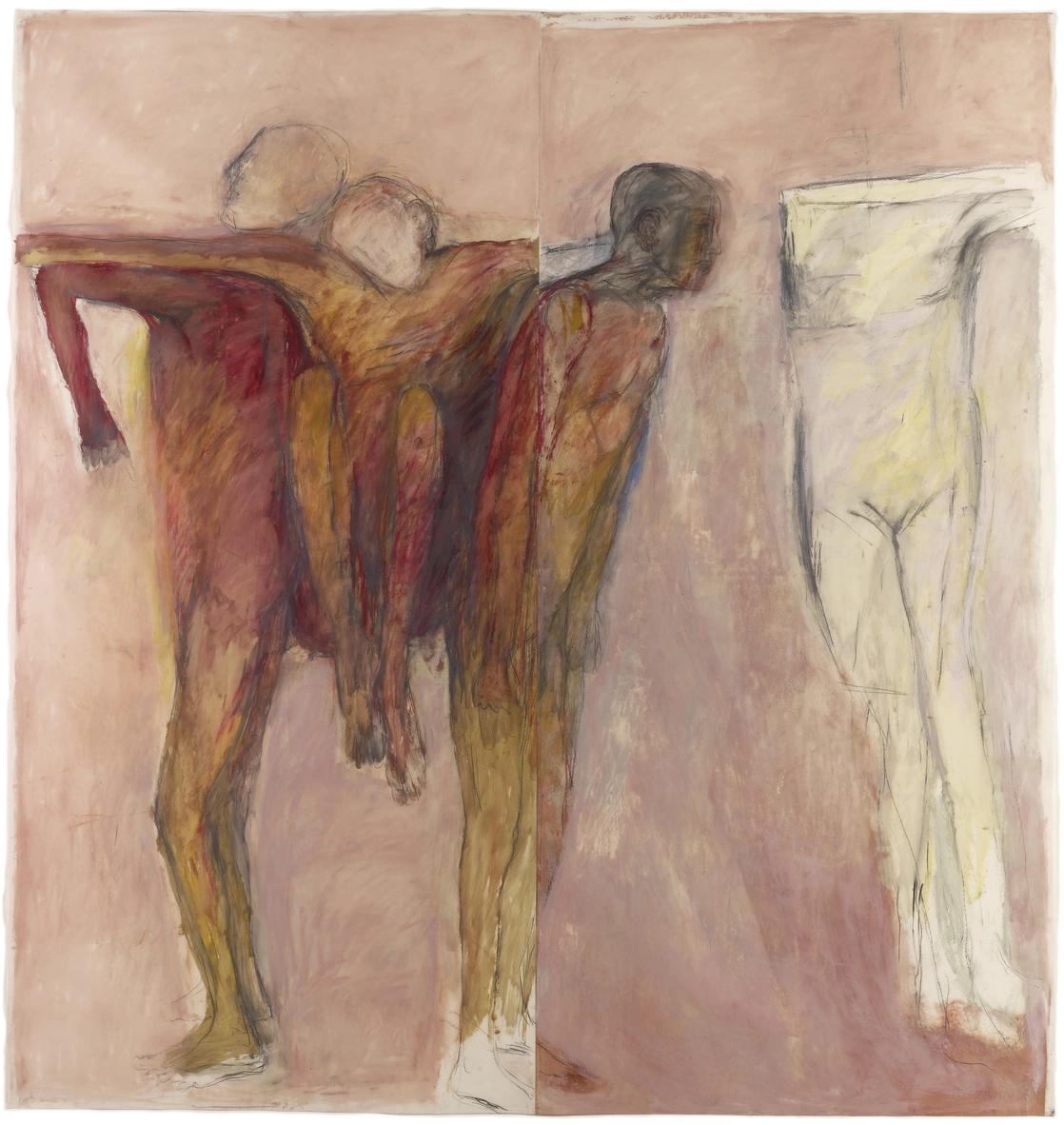

Goodwin by now had solid grounding in two reputed galleries and a new purpose-built studio and residence, completed in 1987, in a former soft-drink factory building on Avenue Coloniale in the Plateau Mont-Royal neighbourhood, where she lived. She was poised to start another prolific phase of work. The following year, her first major museum retrospective, Betty Goodwin: Works from 1971 to 1987, was presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Her preoccupation with terrorist events worldwide and human suffering had led to several series of arresting drawings linked by themes of torture and interrogation. Critic Robert Enright aptly summed up Goodwin’s absorption of current affairs in her work, describing her sensitivity as that of a “sort of human seismograph, registering the slightest change in the anxious atmosphere of the late 20th century.” In such works as Two Hooded Figures with Chair, No. 2, 1988, her subjects operate as charged, androgynous bodies—human symbols rather than actors in specific events. Goodwin’s expansive and luminous new studio space allowed her to leave large drawings, such as Figure/Animal Series #1, 1990–91, pinned to the walls and return to them over time as she worked on multiple series simultaneously and began to integrate sculptural elements with her drawings.

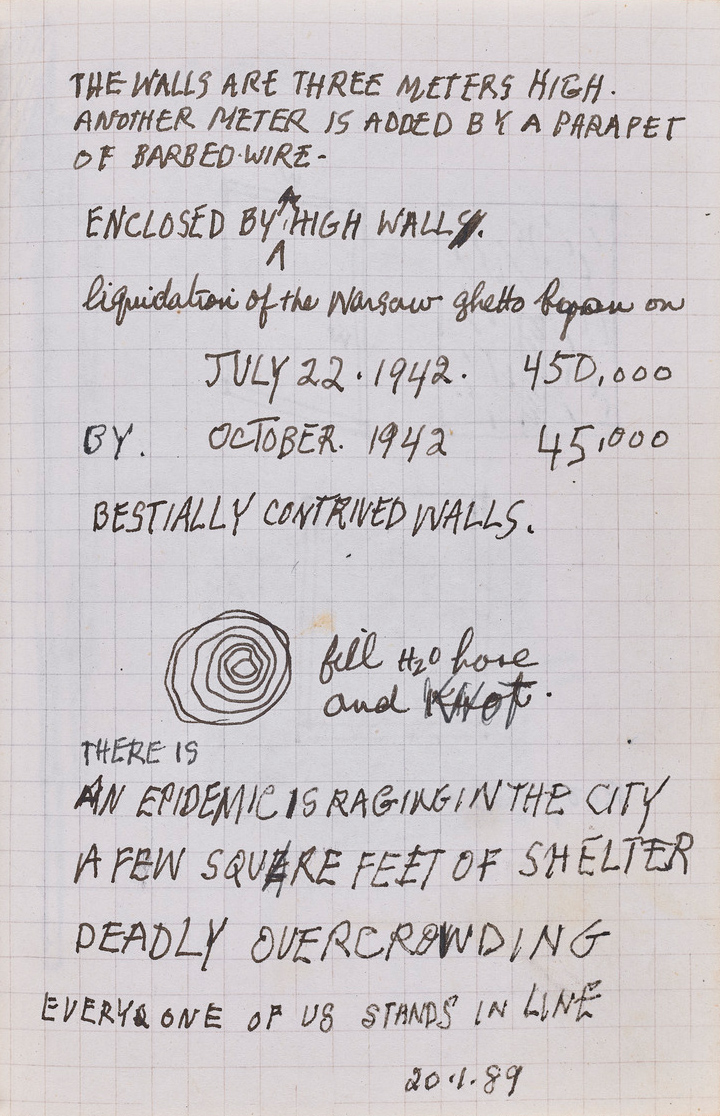

In 1989, Goodwin became Canada’s representing artist in the 20a Bienal de São Paulo in Brazil, where, along with several drawings, she showed a new series of steel tablets with texts, magnets, and iron filings entitled Steel Notes, 1988–89. Two years later, she experienced another deep personal loss with the death of her beloved assistant Marcel Lemyre due to AIDS-related illness. Large figure drawings she made in this period reflect this loss. She also began work on two extended and elegiac series embodying the fragility of life, La Mémoire du corps (The Memory of the Body), 1990–95, and Nerves, 1993–95. Her notebooks from this period reveal her readings on the Holocaust, as do her collections of newspaper clippings, pointing to a more explicit reflection on loss and her Jewish heritage.

Continued Recognition & Legacy

As Goodwin’s reputation grew, her assistants (for two decades and most intimately, Marcel Lemyre, and after his death in 1991, Scott McMorran) worked with her daily and managed the studio. Along with gallerists René Blouin and Roger Bellemare, her husband Martin, and his friend Gaétan Charbonneau, they formed a close-knit family that supported her work and her fragile emotions as the rising demands on her to travel abroad to exhibition openings expanded.

Blouin and Goodwin often travelled together and, on those occasions, her notebooks reveal that she continued to look intently at the work of her international contemporaries, such as Joseph Beuys, Bruce Nauman (b.1941), and Nancy Spero (1926–2009). Her practice, meanwhile, was drawing more attention as Blouin worked with his contacts in New York. He and Pierre Théberge (1942–2018), by then director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, also solicited interest from curators in Europe. Goodwin received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1988. The following year, her art was featured in a solo exhibition at the Kunstmuseum in Bern, Switzerland, and an exhibition in France followed, organized by the Ferme du Buisson, Noisiel, in 1994. The next year, Goodwin was invited to participate in the 46th Biennale di Venezia, in the central exhibition Identity and Alterity. Back home in Canada, the Art Gallery of Windsor (now Art Windsor-Essex) and the National Gallery of Canada collaborated to mount Betty Goodwin: Signs of Life, an exhibition representing the preceding fifteen years of her work. Goodwin received the Gershon Iskowitz Prize in 1995, and in 1998 she was presented with the first Harold Town Prize for Drawing.

In 1996, the Art Gallery of Ontario announced Betty and Martin Goodwin’s gift of 150 of her works as well as the purchase of 18 more, thereby establishing the largest holdings of her art in a public institution. Subsequently, in 1999, the Art Gallery of Ontario presented The Art of Betty Goodwin, a major exhibition with a multi-authored publication. For the next decade, Goodwin showed regularly at her galleries in Montreal, Toronto, and New York, and in 2002 her printmaking was celebrated by the National Gallery of Canada with a comprehensive exhibition and catalogue raisonné. The following year she received both a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts and was made an Officer of the Order of Canada. While she continued to work in her studio, by the end of this more than five-year period of celebration of her achievements, her pace was slowing. Goodwin was beginning to fatigue and withdraw. In her Beyond Chaos series, 1998–99, figures are caught in spirals of time and float in drawings generated from photographs of clouds.

The final five years of Goodwin’s life were spent quietly in her Montreal home and studio. She died on December 1, 2008. In 2009, her work was celebrated by the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal with an exhibition and publication featuring the museum’s collection of her oeuvre. Goodwin’s contribution to Canadian art continued to be honoured in museums and galleries across the country.

Goodwin’s medium of choice evolved over four decades, but her commitment to the figure never wavered. She plumbed the paradoxes of human existence in a prodigious range of work using the body—through its presence or absence—as a metaphor for memory, mourning, and the fragility of life. With expansive scale and remarkable intensity in works such as the Swimmers series, 1982–88, she claimed drawing as a primary rather than preliminary medium. By the time of her death, Goodwin’s unmistakable material language of figuration was celebrated nationally and recognized internationally.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements