As an abstract painter, Bertram Brooker aligned in his own compositions his belief in his philosophy of Ultimatism and spiritualism, knowledge of contemporary cutting-edge art, and interest in music. Through his involvement with artist groups and as a journalist and editor, he forwarded modernist principles in Canadian art. Brooker’s relentless exploration of new ways of seeing and painting situates him among this country’s most accomplished early modernist painters.

Philosophy and Spirituality

Intrigued by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), Brooker includes in his early drawings (c.1912–13) a rendition of a character he called “Ultrahomo the Prophet.” Ultrahomo was his name for Nietzsche’s heroic Superman, or overman (the Übermensch).

Brooker may have admired the Superman but as a Christian, he was skeptical of Nietzsche’s atheism and promotion of violence to achieve a new spiritual order. Around 1912, Brooker developed his doctrine of Ultimatism, which can be linked to the German philosopher’s thinking but also significantly differs from it. According to Brooker, an Ultimatist was one of a very select group of people with the power to unshackle humanity’s reliance on materialism and, thus, liberate humankind’s essentially spiritual nature. The Ultimatists—through the power of art—could show humanity the way forward. Like Nietzsche’s Superman, the Ultimatists searched for that which was “mystical, holistic, and quite self-consciously anti-utilitarian and anti-rationalist.” But in contradistinction to Nietzsche’s idealized human, they believed in a spiritual existence beyond the material.

According to Brooker, there were only three Ultimatists—himself and two celebrities he had never met nor seems to have been in contact with: experimental English stage designer Gordon Craig (1872–1966) and South African writer Olive Schreiner (1855–1920). Ultimatism was never a movement; it was the creation of Brooker’s imagination. He believed that he, Craig, and Schreiner had the power to develop a workable synthesis between materialism and spirituality. His continuing belief in Ultimatism underlies much of his later work, as in Resolution, c.1929, a painting about the quest to become united with the divine.

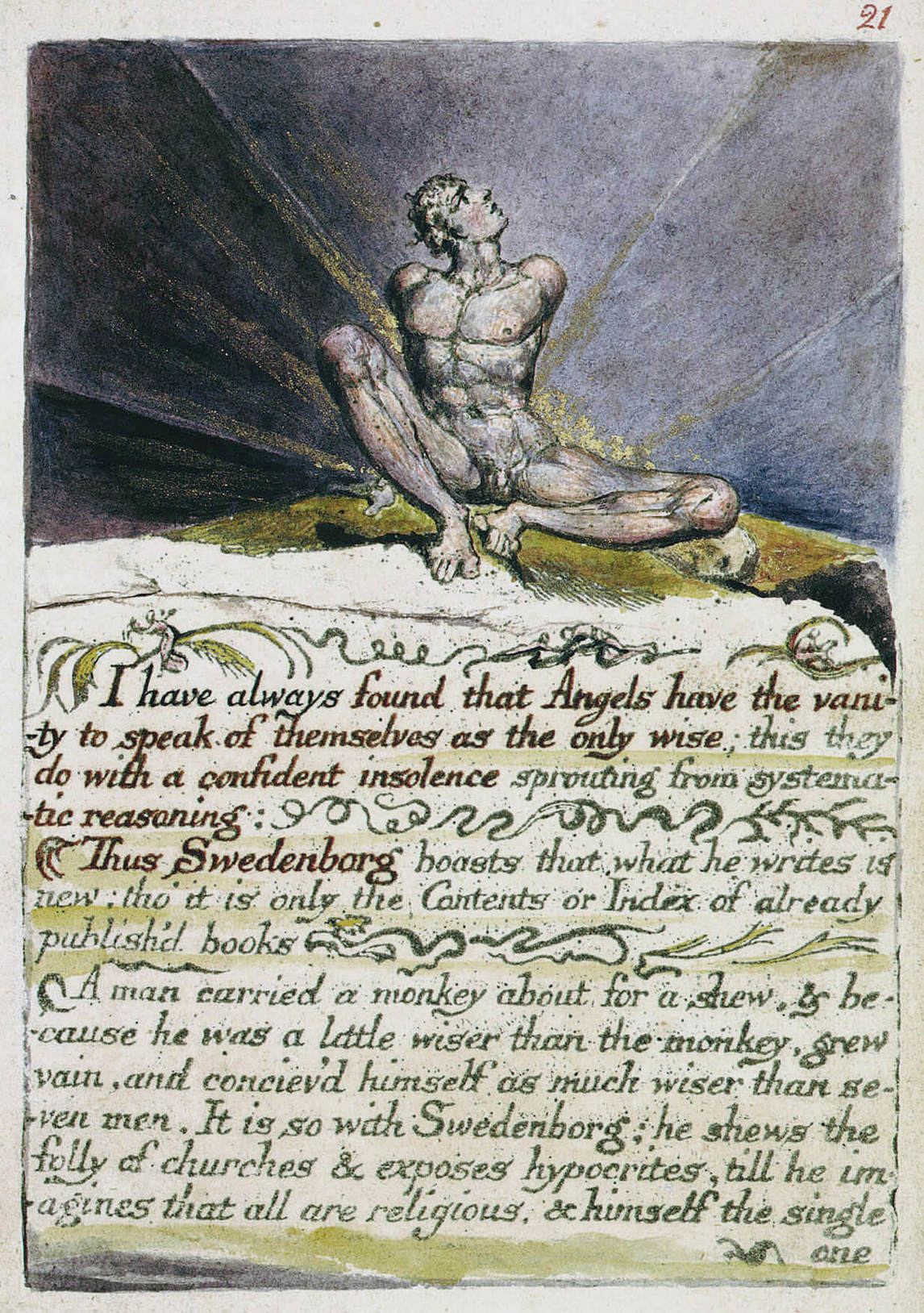

Brooker was intrigued by the spiritual world, which he believed to be hovering on the edge of the material one. As an artist he sought to convey something beyond the tangible. Adam Lauder argues that too much attention has been directed at Brooker’s spiritualism: His “awareness of contemporary developments in the biological sciences contradicts characterizations of [Brooker] as a ‘mystic.’” Lauder proposes that Brooker’s knowledge of and interest in science negates his spiritualism, as might be seen in such works as Ovalescence, c.1954. However, Brooker regarded the two as separate but not mutually exclusive—though the foundation of his beliefs was his adherence to spiritual values. Another way of understanding Brooker is as an artist with visionary and mystical inclinations, very much in the tradition of William Blake (1757–1827). Joyce Zemans has observed that like Blake, Brooker “saw artistic endeavours in all media as evidence of the artist/prophet’s responsibility to offer leadership and to seek truth through creative art.”

However, as David Arnason has suggested, Brooker’s spiritual values were very much of the nineteenth century, when traditional religious values were being challenged by scientific data collected by the likes of Charles Darwin. Brooker’s spiritualism arose, in part, because of his abhorrence of pure materialism. Brooker displays a strong conservative side by adhering to traditional Christian values and well-established transcendent doctrines. However, he sought to meld the old with the new. For instance, he was fascinated by electricity and other new technologies, as can be seen in Crucifixion, 1927–28.

Brooker’s spiritualism coexisted with conventional Christian beliefs. Nevertheless, he does not resort to Christian theology or terminology in his writings and there is almost no Christian iconography in his paintings. In a diary entry of August 25, 1925, two years after a life-changing epiphany at a Presbyterian church, he wrote about “unitude,” or cosmic consciousness, expressing the bedrock of his religious belief:

Stronger today than anytime has come the feeling of all being One. What I mean is that although I have felt as full of divine energy before, and experienced a sort of Oneness, I have never felt kinship with every dead and living thing. . . . The sense, in short of the whole being of God working out his destiny, and I a part, not less nor more than the rest.

While Brooker’s mystical leanings may be characterized as old-fashioned, he used twentieth-century means to realize his vision. In his critical writings he espoused many traditional values, but he always judged the works of other artists on their ability to encapsulate their ideas in modernist ways. For him, a modernist sought to find new formalist techniques to encompass contemporary ideas. Just as Blake’s mystical leanings were inspired by a host of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sources, Brooker’s spiritually charged illuminated books about the transcendent, such as Elijah, 1929, were experimental and trail-blazing. From about 1929 Brooker’s work evolved from abstraction toward representation. His hybrid style, however, does not mean that he abandoned his spiritualist ideas; it merely indicates that he found other modernist ways of expressing them, as can be seen in Entombment, 1937, and Quebec Impression, 1942.

Promoting Canadian Art

From 1923 Brooker was actively involved in helping to build the Canadian art scene, although he did so according to his beliefs, which did not always concur with those of his contemporaries. He forged alliances within the Group of Seven. In 1933 he became a founding member of the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP) and took part in planning its exhibition schedule and in judging submissions. He also published art criticism, and in his nationally syndicated “Seven Arts” columns and in two editions of the book Yearbook of the Arts in Canada 1928–1929 and 1936 he promoted many kinds of artists in Canada.

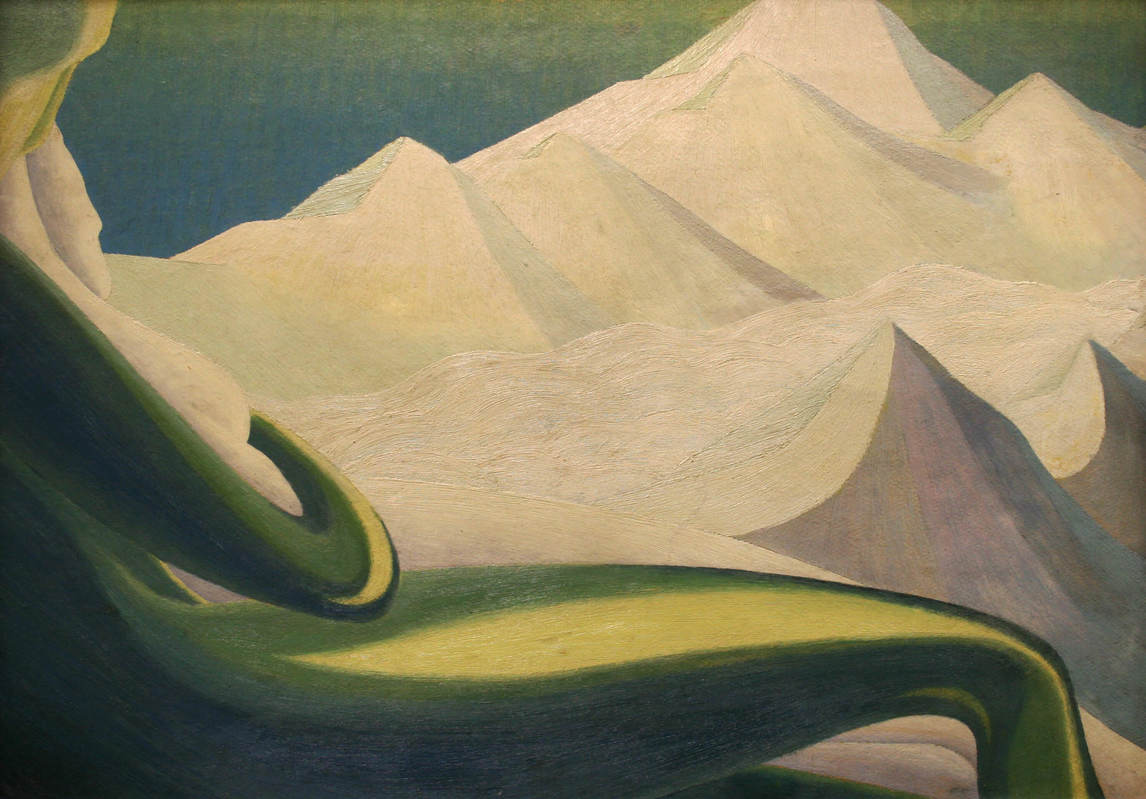

Brooker’s relationship with the Group of Seven was complicated and conflicted. He was drawn to Lawren Harris (1885–1970), in particular, for his belief in the spiritual in art, but did not fully ascribe to the Group’s goals. In October 1929 Brooker publicly questioned the Group’s political agenda. He wrote that: they “are modern only in the sense of being contemporary: they are not ‘modern’ in the generally accepted sense of belonging to the special tendency in painting that stems from Cézanne.” Brooker almost certainly saw himself as part of this “special tendency.” For him, the modernist elements in the works of members of the Group were not truly avant-garde. They may have been superb colourists, but they were not what he considered cutting-edge, as perhaps can be seen in comparing Endless Dawn, 1927, by Brooker, with Mountain Form IV (Rocky Mountain Painting XIV), 1927, by Harris.

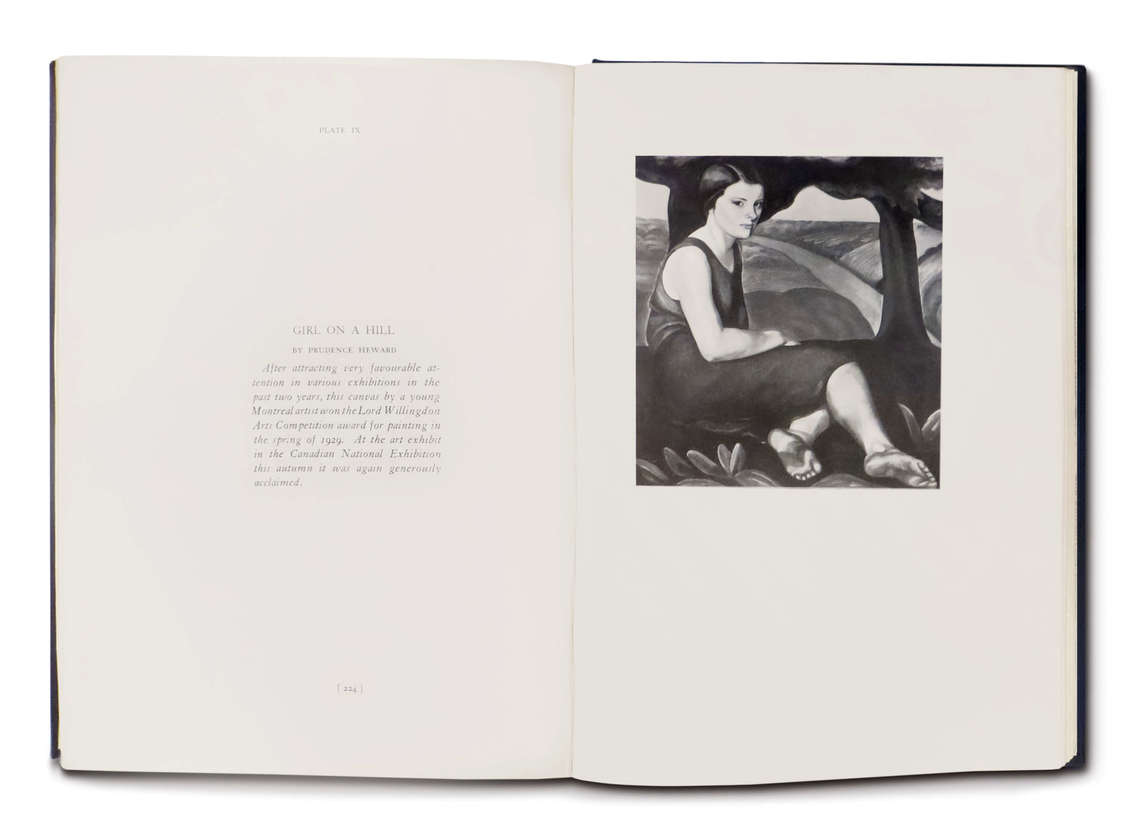

Brooker’s differences with the Group are made evident by the work he selected to reproduce in the 1928–29 Yearbook of the Arts in Canada (for example, Prudence Heward’s Girl on a Hill, 1928, and Kathleen Munn’s Composition [Horses], c.1927) where, as Anna Hudson argues, he shifts “expression of the Canadian landscape . . . from a highly personal engagement with the wilderness to a fascination with the imprint of human settlement.” This new concept of national culture “would redress, so Brooker believed, the linguistic, racial, and economic divisions that fragmented a widely dispersed Canadian population.” From its outset, the CGP had advocated the notion of a national consciousness that found its expression in community, and Brooker placed great emphasis on this idea. The CGP comprised Canadian nationalists but they worked in a much wider variety of genres than the Group of Seven, whose wilderness landscapes remain its greatest accomplishment.

Beyond Brooker’s involvement with the CGP was the outstanding job he did in promoting the works of many of his fellow artists in the two editions of Yearbook of the Arts in Canada. As Anna Hudson states,

It was Brooker’s idea to publish a 1928–1929 Yearbook of the Arts in Canada. The yearbook served as a compendium of a closely knit, younger generation of Toronto painters [and others across Canada]. Although originally intended to be an annual publication, the next and last yearbook did not appear until 1936. By this point, the Toronto community of painters had evolved into a stable artistic community.

Brooker’s efforts as an essayist, notably in his “Seven Arts” columns, and as an editor were crucial in promoting the work of Canadian artists and in establishing a critical foundation for their appreciation.

The American critic and scholar Walter Abell (1897–1956), during his sixteen years in Canada (from 1928 to 1944), argued that art should serve democracy and that, in order to do so, “art” had to be thought of in wider terms than just fine arts; it had to embrace architecture, town planning, and the industrial arts. Brooker’s rigid separation of art and politics was at odds with Abell. More in keeping with Brooker’s point of view are essays by Northrop Frye (1912–1991), such as “David Milne: An Appreciation” (1948) and his introduction to the book Lawren Harris (1969), in which Frye applied an archetypal criticism to visual art. Brooker, Abell, and Frye turned their attention to Canadian art as a topic worthy of serious attention and, in so doing, helped to form a cultural climate in which it could be more fully understood and appreciated and studied.

Colour and Music

Well before Brooker, art critic Walter Pater (1839–1894) had proclaimed that “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music,” and Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) had written, “A painter who finds no satisfaction in mere representation, however artistic, in his longing to express his internal life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the least materialistic of the arts today, achieves this end.” Also influenced by Kandinsky, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) began “painting music” in 1918 (for example, in Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918). At about the same time, Paul Klee (1879–1940), a trained musician, experimented with conjoining music and painting. Brooker was well aware of Kandinsky’s sentiments—and undoubtedly was inspired by them.

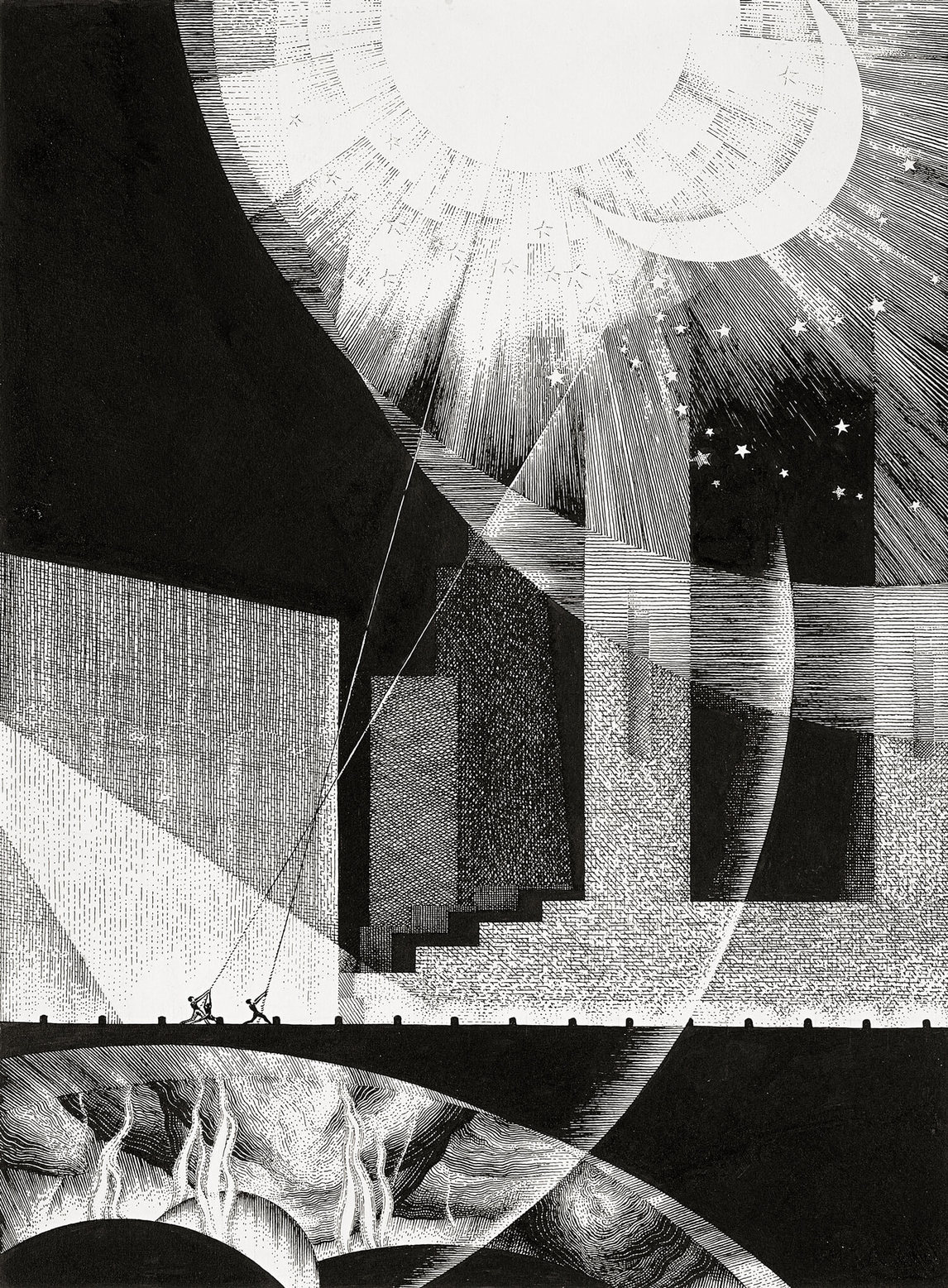

For Brooker the intense enjoyment of music was in direct proportion to the ability of the hearer to divorce himself from physical reality. Music became a means that transported him from the world of everyday to the world of aesthetic exaltation, as in Abstraction, Music, 1927, and “Chorale” (Bach), c.1927. In addition, music provided the central means of creative expression that would allow the visual artist to enter the fourth dimension, a spiritual realm from which contemporary man had excluded himself.

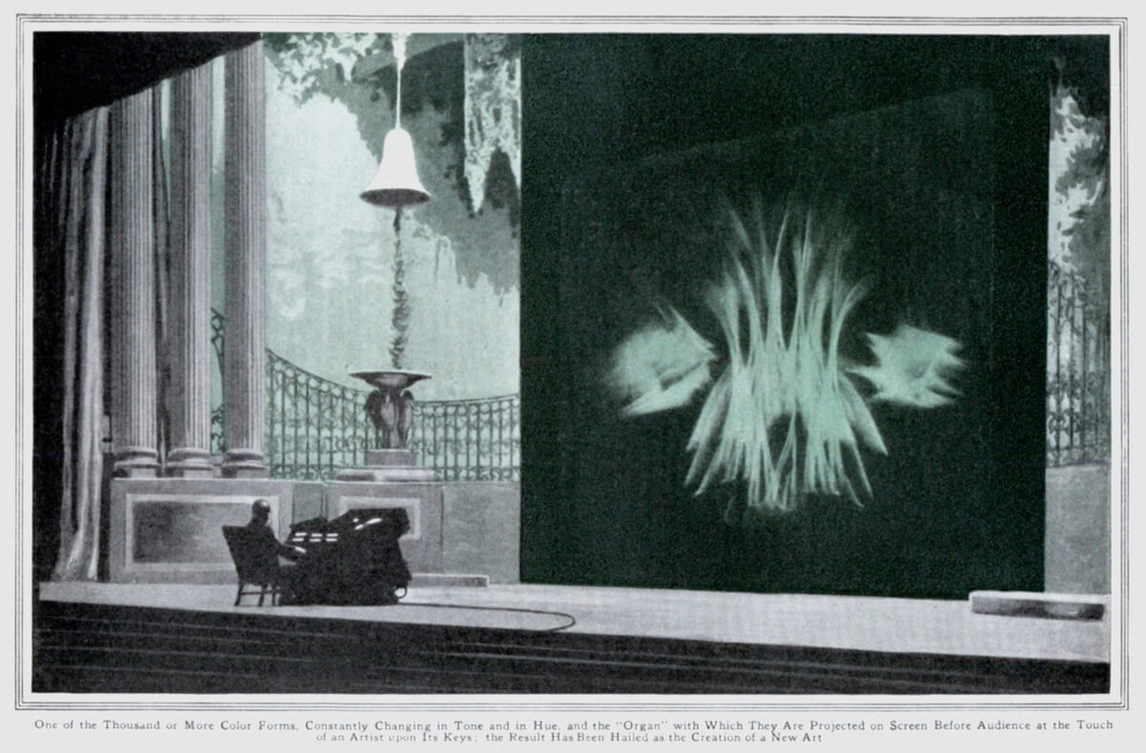

On February 25, 1929, Brooker experienced a very specific instance of how music and nonfigurative visual art could be melded. On a trip to New York, he and his wife “had dinner with Thomas Wilfred, the inventor of the Clavilux [light played by key] known as the ‘colour organ’ which projects moving forms and colours on a lighted screen.” It is clear Brooker attended a performance during the trip, but it is likely that he had read about Wilfred four or five years earlier.

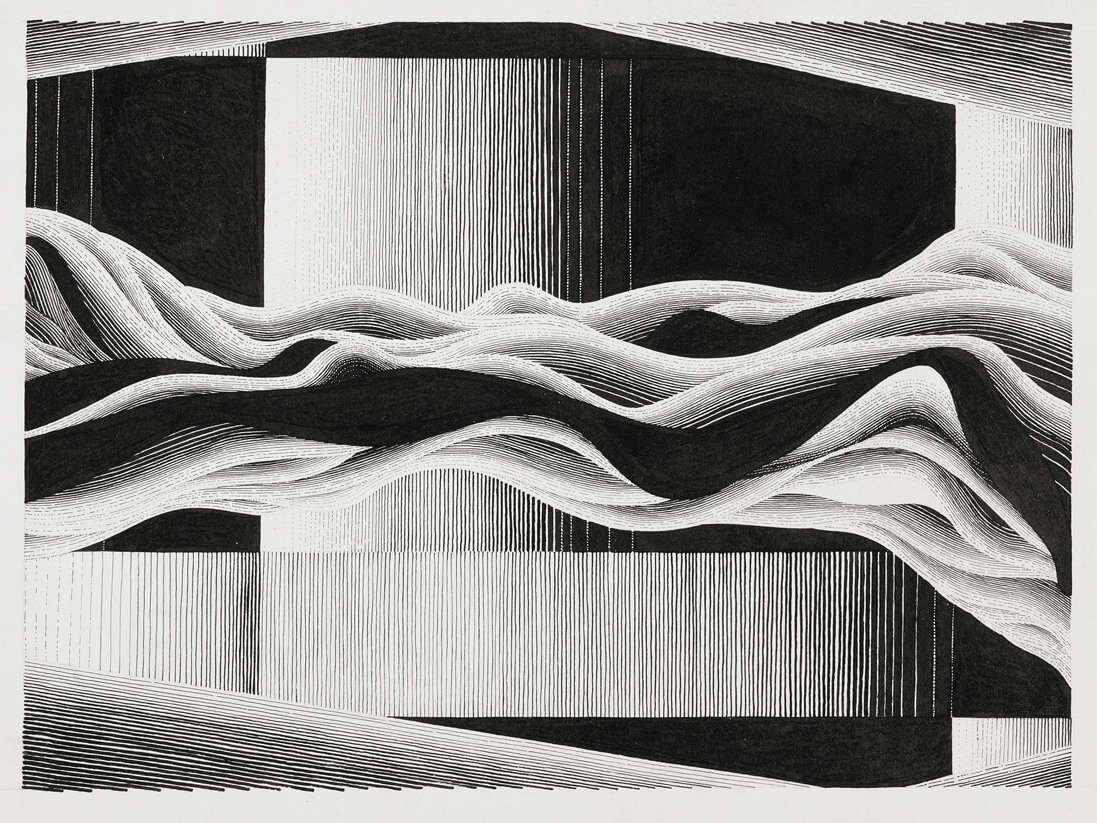

In a canvas such as Evolution, 1929, Brooker creates a stolid pedestal-like foundation at the bottom, but most of the picture area is dominated by a wide variety of shapes: on the extreme right, some tubular forms mount upwards; in the centre is a quiet-looking ovoid shape, while various shards move downwards from the left, intersecting with several triangles. Each of these forms is coloured somberly but differently. The composition of this picture, and of other musically inspired abstracts, such as the pen-and-ink drawings Fugue and Symphonic Movement No. 1, both c.1928–29, might be Brooker’s attempt to find a way to capture one of Wilfred’s performances.

Throughout his life as an artist, Brooker remained remarkably consistent in his attempts to align visual forms with musical ones. In Wilfred, he saw a methodology that he could adapt for his own purposes.

Dimensionality and Time

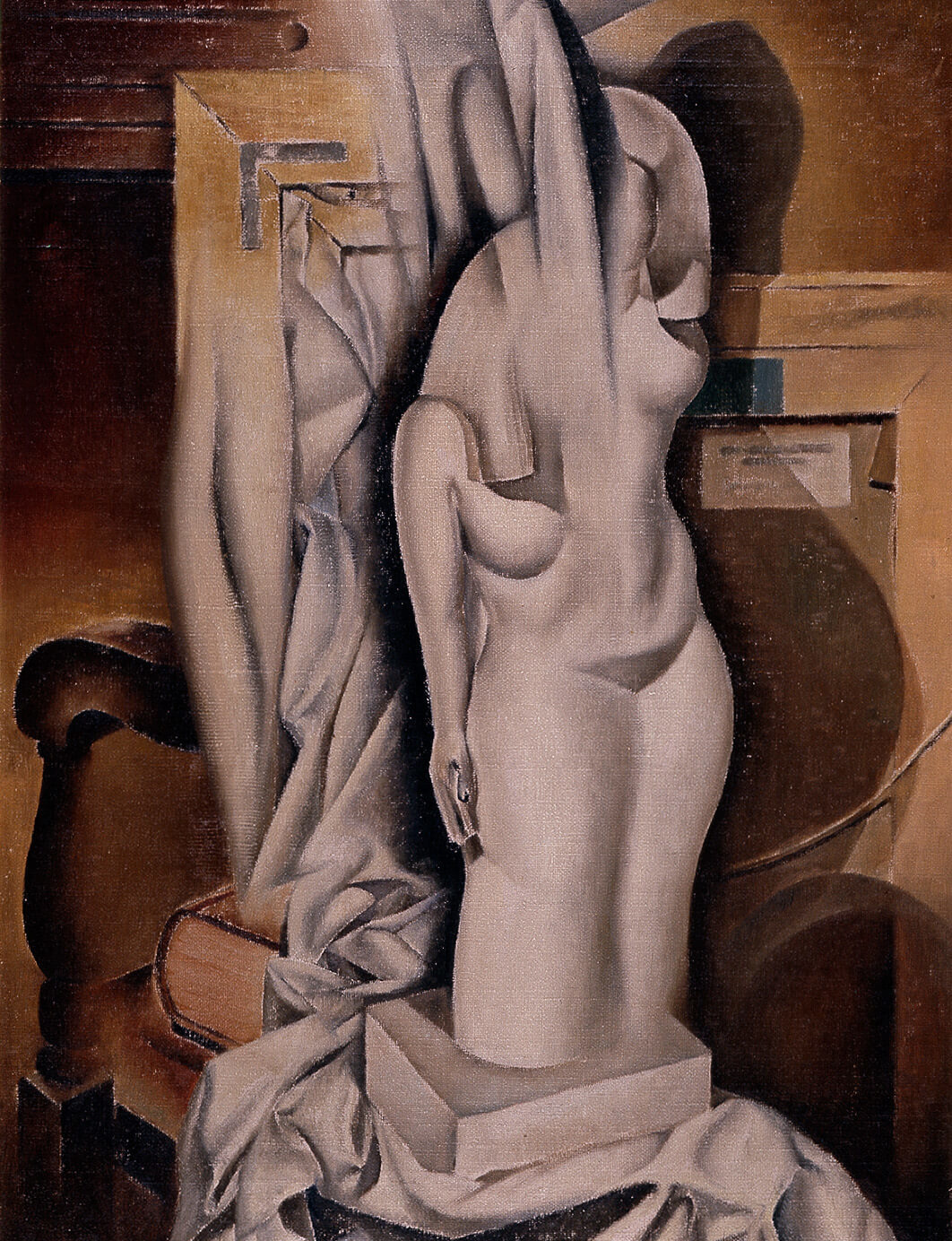

Brooker wanted to create works of art in which duration, or time, could be “seen.” All Brooker’s abstracts from 1927 to 1931—for example, Alleluiah, 1929, and Resolution, c.1929—were likely influenced by the theory of time conceived by Henri Bergson (1859–1941). They depict abstract landscapes meant to inhabit the fourth dimension (where the laws of “duration” are suspended) and provide glimpses of a terrain not seen by most human beings. He also approached the concept of time in representational works, such as his nude Pygmalion’s Miracle, c.1941, in which a sculpted figure resides. The figure represents the past but she exists in a terrain beyond ordinary time, and her metamorphosis into flesh may represent Bergsonian duration.

Bertram Brooker, Creation, 1925, oil on board,

61 x 43.2 cm, private collection.

Bertram Brooker, Machine World, 1950, oil on canvas, 45 x 36 cm, private collection.

Brooker’s children remembered that he often encouraged them to “imagine perceiving three-dimensional objects in a two-dimensional world to stress the validity of the fourth dimension.” Brooker’s early and later abstracts, such as Creation, 1925, and Machine World, 1950, emphasize “dimensionality,” which he also referred to the fourth dimension, and which he defined as creating “instead of the usual space perspective that makes a painting three-dimensional, a new and puzzling illusion of space that is foreign to normal visual experience.” Joyce Zemans observes that for Brooker and other abstract artists, “the concept of higher dimensions of space seemed also to offer the visual artist the opportunity to capture a truer reality than that offered by representation or even symbolism.”

Brooker uses “fourth dimension” loosely. In mathematical theory, the term refers to adding another spatial dimension to one-, two-, and three-dimensional space (length, area, and volume). Brooker believed that the fourth dimension was best captured in “the mathematical and the musical.” He asserted that in the fourth dimension it is possible to come into contact with “the intellectual re-arrangement of facts and concepts in new patterns.“ Brooker means that the existence of the fourth dimension points to a level of reality from which most—except those who have obtained cosmic consciousness—are excluded.

By entering the fourth dimension, the artist takes himself out of time in any conventional understanding of the term. In this regard, Bergson’s concept of “duration” became central to Brooker’s thinking and can be seen in paintings such as Abstraction, Music, 1927. The French philosopher had rejected a materialist interpretation of time and substituted one that allowed entry into a different realm of existence.

Abstract Art

Although there are instances of abstract art well before the twentieth century, compositions that depart from the various modes of representation in Western art came to the fore in the early twentieth century. Artists began to feel that the “modern” world needed a truly modernist modality to capture its essence. Such pursuits led in various directions, but one important strand was influenced by, among others, Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891), George Gurdjieff (1866–1949), and P.D. Ouspensky (1878–1947), who wrote about the connection between the material and spiritual worlds. Such writings especially influenced Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), and Wassily Kandinsky.

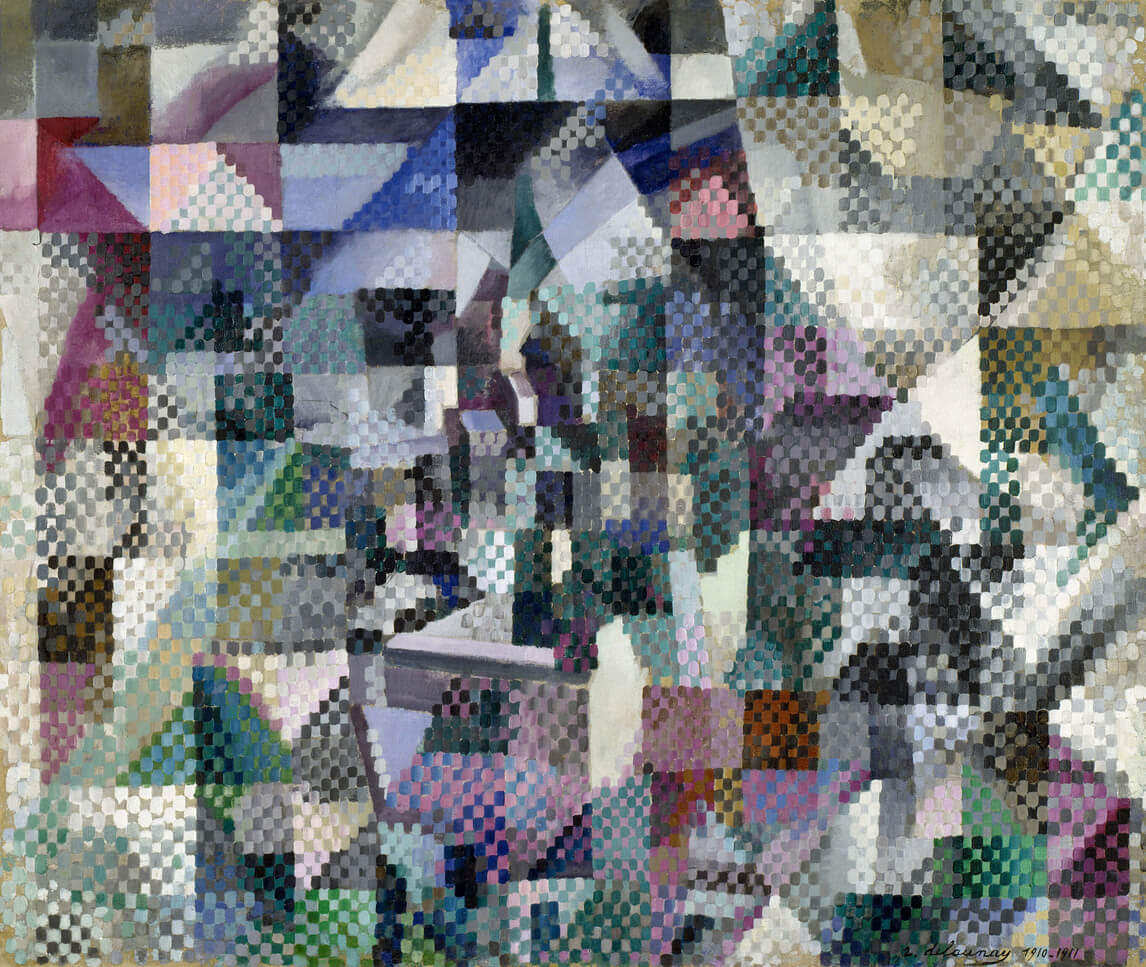

A forerunner of abstract art in Canada, Brooker was well aware of the work shown in 1913 at the Armory Show, and his early drawings are mainly copies of works that were exhibited there, which he likely saw in reproduction. Many new ways of making art were on display, including major pieces of Cubism, but there were some bold attempts at abstraction, including Window on the City, No. 3 (La fenêtre sur la ville no 3), 1911–12, by Robert Delaunay (1885–1941); The Procession, Seville, 1912, by Francis Picabia (1879–1953); and Improvisation 27 (Garden of Love II), 1912, by Kandinsky. Each of these abstract canvases bears only a superficial resemblance to one another. In the same way, some of Brooker’s abstracts have similarities to the work of the Italian Futurist Giacomo Balla (1871–1958), as can be seen in comparing Brooker’s Sounds Assembling, 1928, with Balla’s Abstract Speed + Sound, 1913–14.

What links Brooker to af Klint and Kandinsky is that all three share a commitment to displaying the spiritual world that is closed off from the material one. Their works differ because each has a distinct take on the spiritual world. For example, af Klint employs a colour scheme not unlike Brooker’s, but her Altarpiece, No. 1, Group X, Altarpieces, 1907, is much more static—and diagrammatic—than Brooker’s comparable excursions into the spiritual world, as seen in The Three Powers, 1929. In contrast, Brooker’s abstracts lack the strong lyrical feelings expressed by Kandinsky.

For Brooker, pure abstraction, as he conceived it, was the gateway to depicting the spiritual world, and from about 1922 to 1931, he sought ways in which he could capture that elusive reality. In so doing, he became the first Canadian artist to employ pure abstraction.

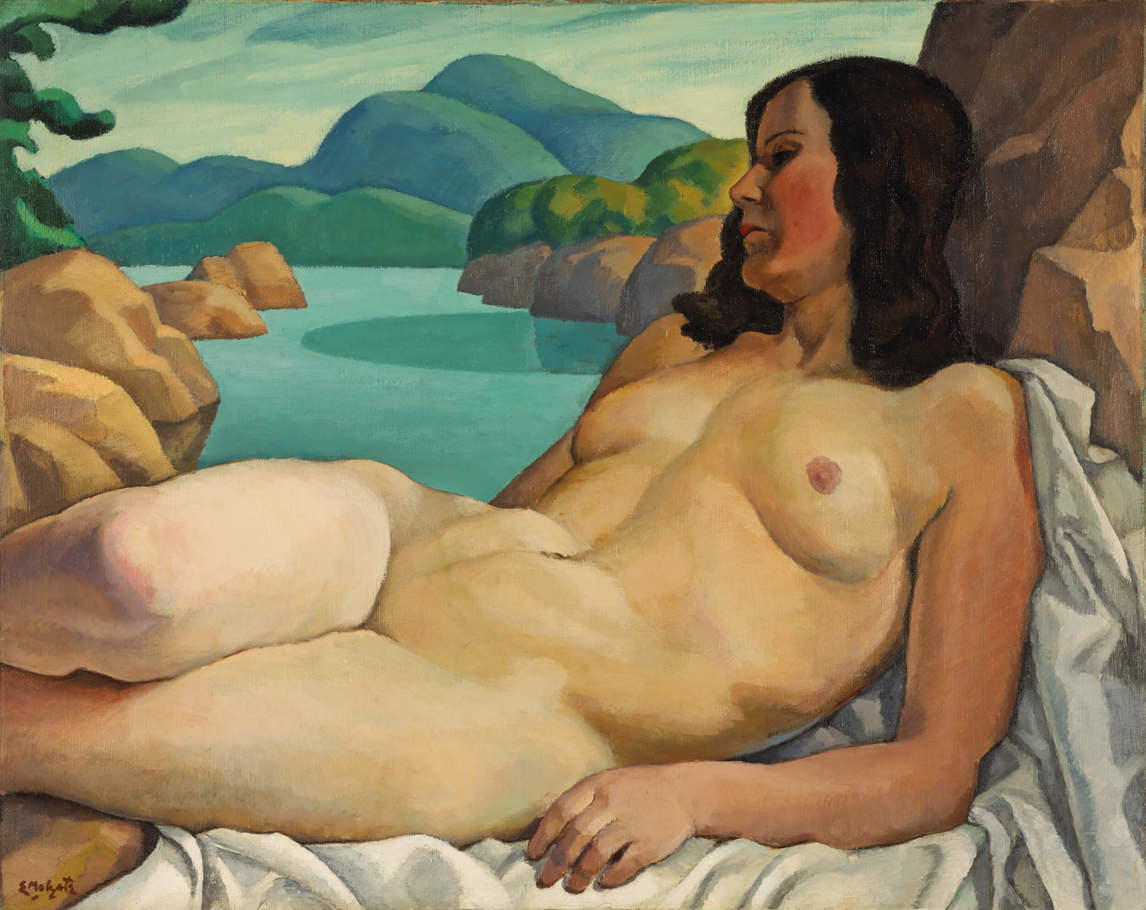

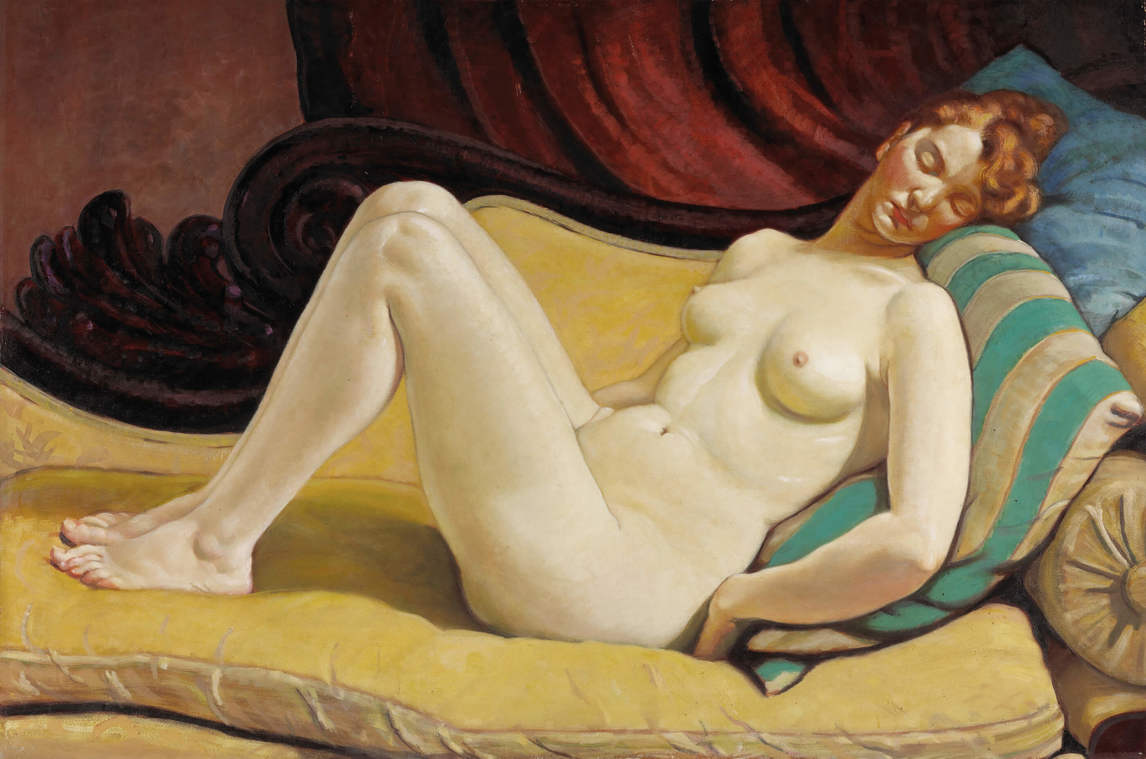

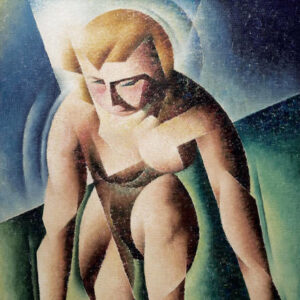

The Nude and Prudery

Despite the fact that the nude is a major, legitimate genre dating back to antiquity, a distinction is sometimes made between representing a nude body and displaying a naked one, a differentiation Brooker found puritanical. Although his Figures in a Landscape, 1931, was accepted for a 1931 exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), it was not hung because it was felt it might negatively affect the sensibilities of children. Brooker did not expect to be censored when he submitted the work. A year before, Edwin Holgate (1892–1977) had shown his Nude in a Landscape, c.1930, in the annual exhibition of Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada without consequence.

Figures in a Landscape had been accepted by the OSA’s exhibition jury and listed in the catalogue. Before the exhibition opened, the local board of education expressed concern that the painting might offend; under the board’s auspices, hundreds of children visited the gallery each week. The president of the OSA and the head curator of the gallery asked the jury to withdraw the canvas. When reporters asked why the painting had not been hung, the response was that the gallery was overcrowded. This obvious mendacity led to intense media scrutiny and stories on the front pages of some newspapers.

An indignant Brooker responded with the essay “Nudes and Prudes,” in a collection of essays called Open Door published in 1931 in Ottawa. He argued that the prudery in response to images of the nude arose in large part because elders in society presumed that the young would be corrupted by public displays of nakedness. He hit out against his opponents vigorously: “Nobody pretends . . . that nude paintings or books which deal frankly with sex are dangerous to the morals of grown men and women . . . . In any case . . . the questions of nudity and [lewdness] become ‘questions’ only because of the young.” And the young, he proclaims, become the victims of educators whose eyes are firmly shut to the realms of the imagination. The result is catastrophic because children are made to feel guilt whereas “art is one method of acquainting children with the organs and functions of the body in an atmosphere of candour and beauty.”

This issue sometimes had a nationalist bias. When Sleeping Woman, c.1929, by Randolph Hewton (1888–1960) was shown in 1930, as Michèle Grandbois points out, “A.Y. Jackson confessed at the time to being troubled by the disparity between this work and what was expected of a true Canadian form of expression, best embodied in the landscape genre. So, even as Canadian art was asserting its modernity, it refused to identify with the nude.” Nude, 1933, by Lilias Torrance Newton (1896–1980) was removed from the 1933 Canadian Group of Painters exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto in part, as the critic Donald Buchanan put it, because the model was “a naked lady, not a nude, for she wore green slippers.”

For Brooker, the nude was a genre that fully liberated his imagination. He could allow his models to block a view, as in Figures in a Landscape, render them in precise, clinical ways, as in Torso, 1937, or place them in a classical context with a playful edge, as in Pygmalion’s Miracle, c.1941. As Anna Hudson has pointed out, he could in Seated Figure, 1935, create a monumental studio nude “whose humanity is profoundly felt in the fleshiness of the model’s abdomen. . . . This ordinary woman is the object of extraordinary intimacy, which in life is fleeting and in art enduring.”

A Multidisciplinary Artist

In whatever genre he worked—in both visual art and writing—Brooker advanced the same ideas: the material must bow to the spiritual; human life should be a process of embracing the otherworldly; Canada must produce its own distinctive art. In addition to his paintings in oil and watercolour and his pen-and-ink drawings, Brooker was adventurous in other forms of visual art—sculpture and stage design. Only two pieces of sculpture by him are known to exist. The best is Triptych, c.1935; the other is Egyptian Lady, c.1939. Cast in bronze, Triptych is difficult to locate in the history of sculpture, but its antecedent is clearly Brooker’s own Evolution, 1929. In both the painting and sculpture, jagged horizontal linear forms on the left ascend steeply in a strong vertical thrust to the right. The movement in both pieces dramatizes the concept of evolution in spiritual terms: the soul of man, as it awakens, moves upwards in a transcendental gesture. As can be seen in Green Movement, c.1927, and Egyptian Woman, 1940, Brooker liked to depict sculptures or sculpture-like forms in his paintings.

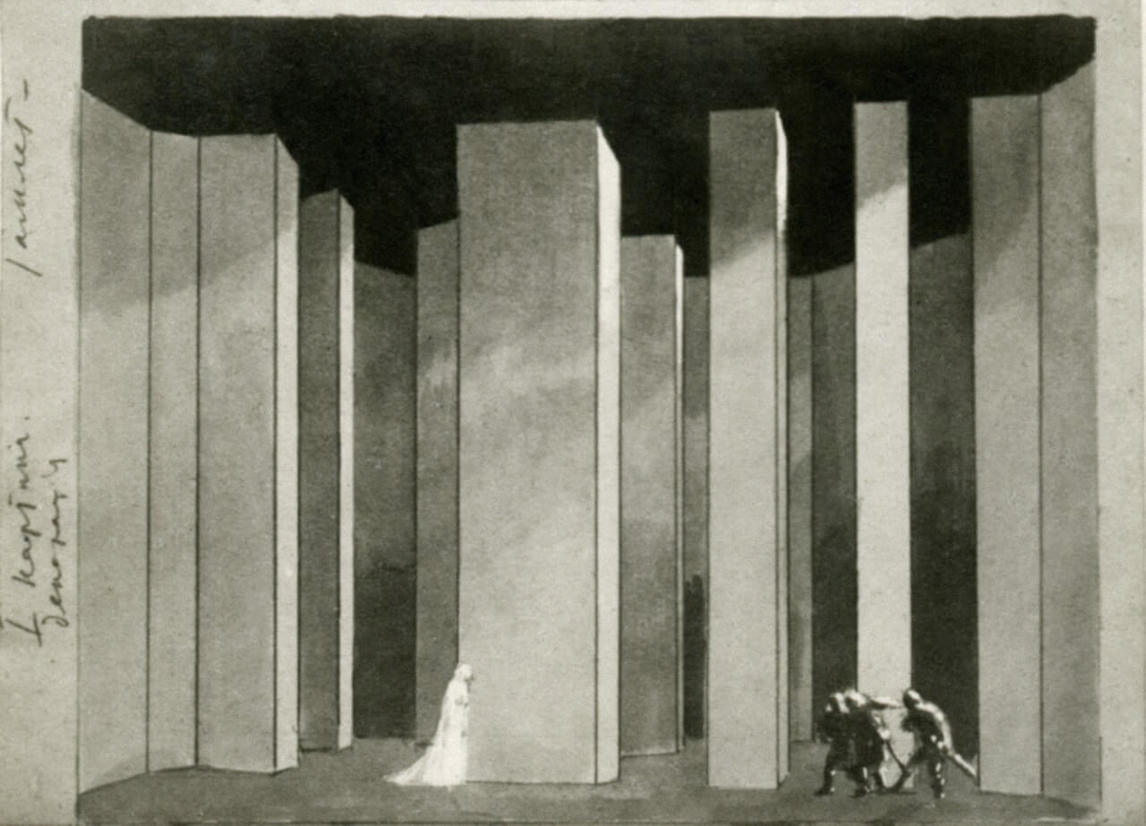

As a young man, Brooker had written film scripts as well as acted and performed in plays. In Toronto he found a kindred spirit in Herman Voaden (1903–1991), who in 1932 called for a Canadian “Art of the Theatre” that would be “an expression of the atmosphere and character of our land as definite as our native-born painting and sculpture.” Drawings such as All the World’s a Stage, 1929, already reflected Brooker’s interest in the theatre. At Voaden’s Workshop at Central High School of Commerce he produced two of Brooker’s plays, Within: A Drama of the Mind in Revolt (1935) and The Dragon (1936). These are expressionistic works in which many of Brooker’s key tenets are advanced. The former is a one-act play set within the interior of an individual’s brain, and the stage design (of which there are two extant) is by Brooker. In the latter, against a series of giant discs, human figures are shown striving between instinct and reason. This drawing, in placing the actors against a stark backdrop, indicates that Brooker relied on revolutionary methodology in stage design of the modernist theatre practitioner Gordon Craig (1872–1966)

Very little is known about the actual production of Within, but Lawrence Mason in the Globe applauded “the choral speaking, masked groups, sculptural poses, shadow effects, contrasting voice-timbres” that left the audience “quite spellbound.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements