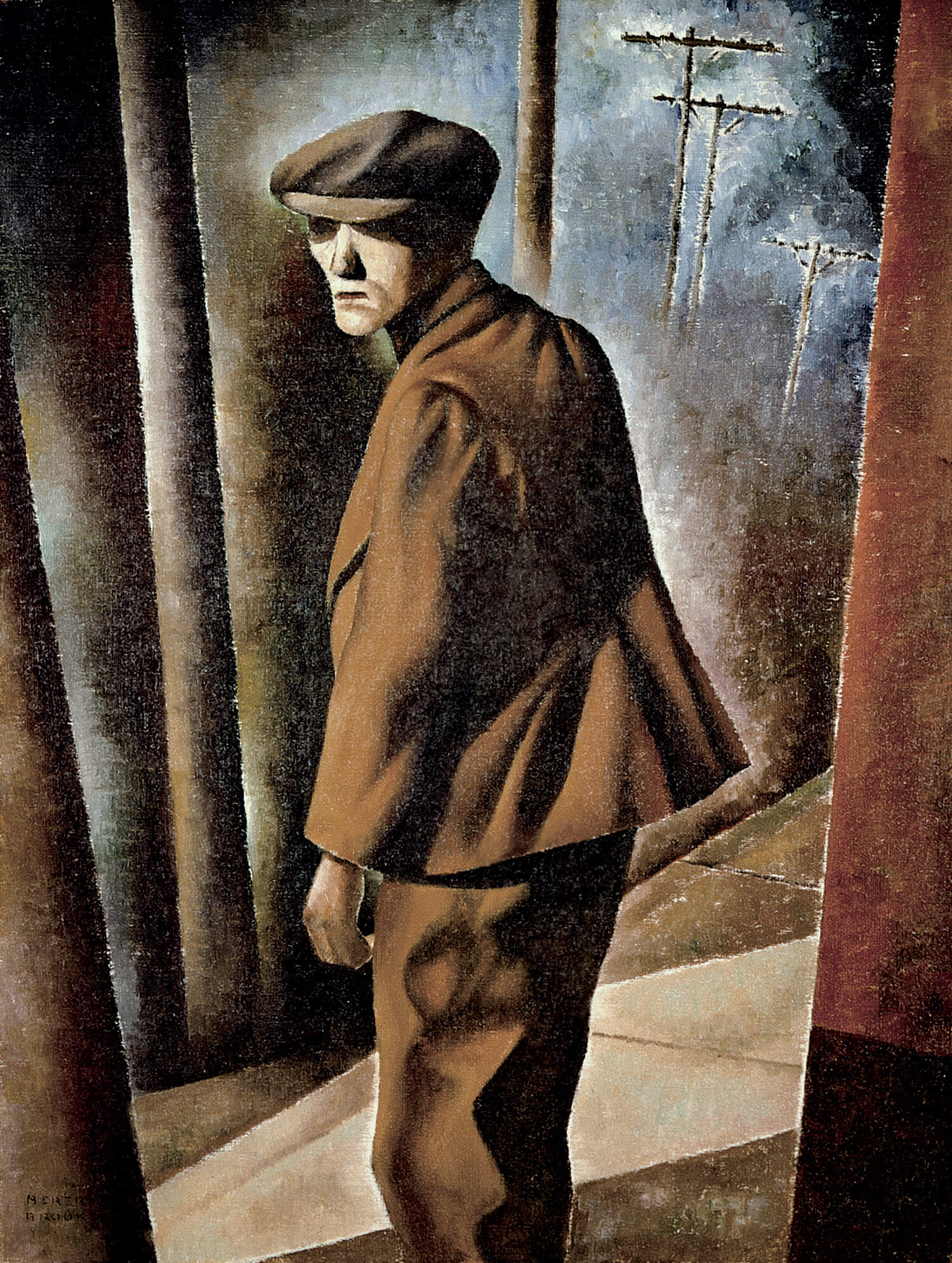

The Recluse 1939

Bertram Brooker, The Recluse, 1939

Oil on canvas, 61 x 45.7 cm

Private collection

This is a painting that evokes Brooker’s social concerns, specifically his compassion for individuals who have been marginalized: the subject is a solitary, unwelcome member of society. As is now customary for Brooker, the representational elements are combined with abstraction. The deeply haunted face of the man turning to stare at the viewer is in sharp contrast to the quasi-geometrical shapes behind him. In addition, as Anna Hudson notes, the three telephone poles recede into space: “Their function is to signal the absence of beauty in urban life, and, by implication, of harmonious social order.”

Brooker’s first surviving oil painting—The Miners, 1922—shows workers on the way to the pit, and suggests that Brooker possessed a strong sense of empathy for the underclass. The Insulted and Injured, 1934–35 (with a title taken from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel of 1861), supports this claim: it is a harrowing indictment of the ghastly settings in which members of the underclass exist. The Recluse also underscores an important principle for Brooker concerning the relationship between social action and artistic practice:

No sensitive man—whether artist or not—can remain unstirred by suffering on so gigantic scale as grips the world at present. As a man—as a citizen—as a member of the human fraternity—the artist should be prepared to do something about it. But, as artist, he should not preach about it. The moment he becomes a missionary he ceases to be an artist.

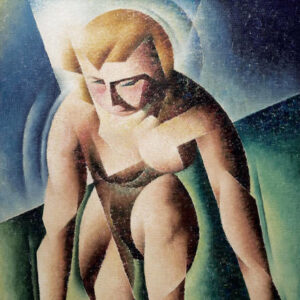

It is not known on whom Brooker based the figure in The Recluse. In some of his abstract works from 1927 to 1931, he had introduced human-like figures. And he became a superb portraitist. In Phyllis (Piano! Piano!), 1934, he poses his daughter seated sideways to the piano. A curious tension exists between the girl with her anxiety-ridden face and careworn hands and the piano behind her. Phyllis stares into space, almost as if pondering the power of the music she has just played—or is about to play. Her cheeks are flushed, but her eyes suggest that she has been in touch with some strong, outward force. In Brooker’s 1932 portrait of the novelist Morley Callaghan, the subject seems about to move forward in space; the suggestion is that Callaghan is a dynamic person, uncomfortable simply sitting still. Brooker’s portraits were not commissioned, and they are few in number; many were done as favours for friends.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements