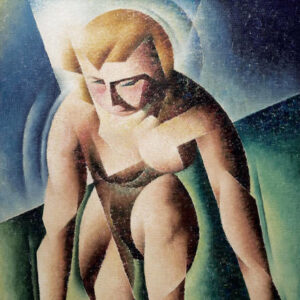

Alleluiah 1929

Bertram Brooker, Alleluiah, 1929

Oil on canvas, 122.2 x 121.9 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Here, against green, purple, and grey mountains and a medium-blue sky, a confrontation takes place between what looks like scaffolding—the sharply defined silver-grey, metal-looking poles—and the deliberately less-distinct white ectoplasm-like substance accompanied by three moon-like circular objects. The interaction between these two kinds of forms—and the fact they find a common meeting ground—originates from Brooker’s attempt to “recreate the intricate polyphony of the Hallelujah Chorus in Handel’s Messiah.” Created in response to a specific musical source, this is the most programmatic of Brooker’s large abstracts. It is also the work in which his reliance on a specific musical analogy is most clearly stated.

Alleluiah is not as overtly dramatic as Sounds Assembling, 1928; its gentle terrain allows the viewer to enter into and experience a quieter realm. Brooker has replaced the dramatic music of the Hallelujah Chorus with a quiet praising of God. The painting seeks to take its viewer into the landscape of intuition and imagination, a sphere that exists beyond the material world and that transcends ordinary space and time.

Here Brooker visually represents his theory of Ultimatism, which posited a realm beyond ordinary human comprehension, and a response to the concept of duration by French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941). According to Bergson, there are two kinds of time: actual physical time as measured scientifically and objectively (for example, by Greenwich Mean Time) and time as experienced subjectively, which speeds up or slows down depending on an individual’s experience. Bergson, in his work, proposes time as duration in a non-quantitative way. As the painting pulls the viewer’s gaze from its jutting, industrial cylinders in the foreground to the ethereal, organic shapes that appear to almost float behind them, Alleluiah inspires viewers to perceive a time and place beyond the mundane.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements