Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) was one of Canada’s first abstract painters. A self-taught polymath, in addition to being a visual artist, Brooker was a Governor General’s Award–winning novelist, as well as a poet, screenwriter, playwright, essayist, copywriter, graphic designer, and advertising executive. Despite Brooker’s lack of formal art training, he painted in a wide variety of styles, creating cutting-edge modernist pictures.

Early Life

Bertram Brooker was born in 1888 in the London, England, suburb of Croydon to working-class parents. His father, Richard, was a railway ticket collector; his mother, Mary Ann (née Skinner), was a homemaker. Bertram had three older siblings, Harry (who died in infancy), Ellen Edith (called Nell), and Ann (who died in infancy); his brother George Cecil (called Cecil) was a year younger. Brooker left school at the age of twelve to work as a domestic servant and then at Fuller’s Dairy in nearby Upper Ashridge to support his family. Despite the brevity of his schooling, he was a self-starter, with an inner drive to teach himself. For example, as a youth, he was an ardent reader (even saving his lunch money to purchase books) and so he remained for the rest of his life.

As a youngster, Brooker was deeply troubled by his brother’s severe asthma. He witnessed the domestic gloom in which his family existed as a result of Cecil’s illness and he began to speculate on issues such as injustice and the existence of God. He undertook a “soul-search” for “reality, truth, God, Christ, proof of the existence of an immortal soul.” For a time, he became intrigued by the cause of gravity and, in general, tried to “square religion with science.”

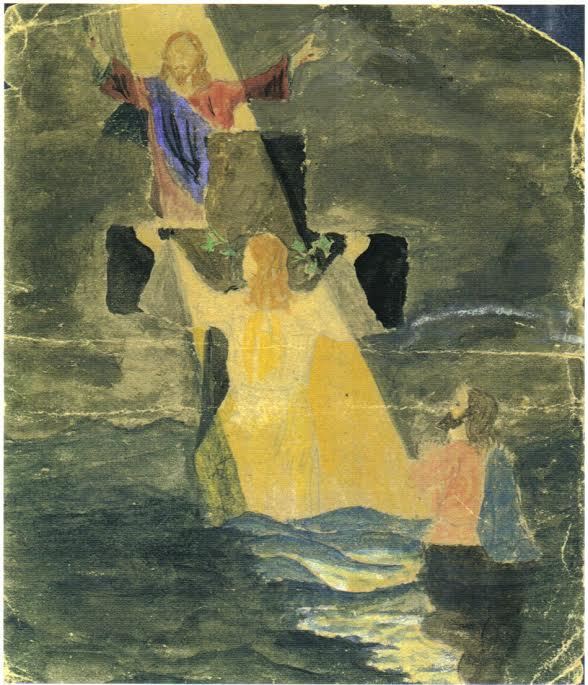

In “The Unknown Caller,” an early, unpublished autobiographical novel (it is not known when Brooker wrote this), Brooker’s protagonist, Bernard, takes such pleasure in colouring that his mother predicts he will become an artist; this character writes stories and believes angels are telling him what to inscribe. A watercolour done in 1899 is Brooker’s first surviving work of art. Painted when he was ten or eleven years old, it features an exultant Christ figure and illustrates the line “Simply to Thy cross I cling” from the celebrated “Rock of Ages” hymn published in 1763.

Young Brooker was drawn to music: at the age of twelve he was a choirboy at St. James Anglican Church in Croydon. He most likely read music, but he did not play an instrument or compose—singing was his main outlet for expressing himself in this sphere.

In early 1905, when Brooker was seventeen, the family immigrated to Portage la Prairie, Manitoba. They picked an exciting time to arrive in the Canadian West. There was a booming economy and a huge influx of immigrants from England and elsewhere in Europe wanting to better their lives. In Portage la Prairie, Brooker worked with his father at the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in a menial capacity. He attended night school and was, as a result, given clerical work at the railway.

Search for a Vision

At some point between 1910 and 1912, when he was in his early twenties, Brooker briefly travelled back to England and then to New York City. The purpose of the trip was to “catch up with drama and literature and art happening.” Unfortunately, no details survive about what art he saw or music he heard. During these trips, he probably encountered modern theatre and likely became instilled with a passion for contemporary art. In London the landmark first Post-Impressionist exhibition, organized by Roger Fry (1866–1934), was on display in 1910, the second in 1912. Works by Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Édouard Manet (1832–1883), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) were featured in both. Had Brooker seen the work of the Ashcan School in New York, it would have been decidedly old-fashioned in comparison. At the same time, 291, the New York gallery of Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), was showing progressive work by the Dadaists, Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), and Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957).

Brooker derived much of his knowledge of the plastic arts and music from books and periodicals. He was intrigued by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), who scorned materialist values and promoted spiritual ones, and around the time that Brooker was travelling (circa 1912), he developed his own theories, in response to his reading of Nietzsche.

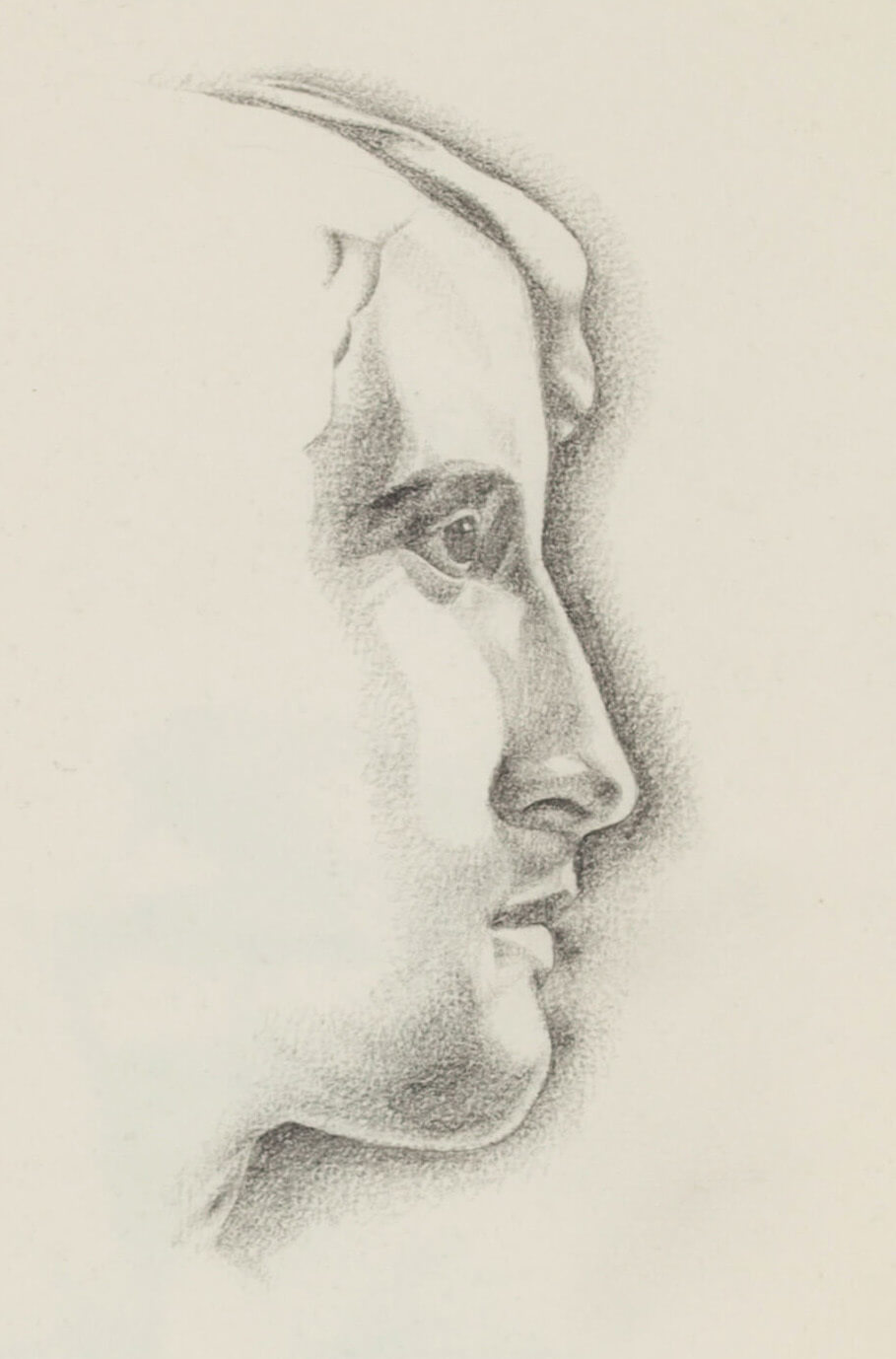

Around 1912–13, soon after his return to Portage la Prairie, Brooker made the first drawings and watercolours of his that survive (apart from the childhood watercolour of 1899). Ultrahomo, c.1912–13, is one such pencil drawing that depicts a version of Nietzsche’s Superman (a heroic figure signalling a new spiritual order). Its sinuous lines show indebtedness to Art Nouveau.

A Love for Theatre

No evidence remains of Brooker’s involvement with drawing or painting following the making of Ultrahomo, c.1912–13, until 1920. But he had found other means of artistic expression. In 1912 he and his brother, Cecil, moved to Neepawa, a small town northeast of Brandon, Manitoba. According to one source, the brothers were “persuaded that motion pictures were the coming thing” and therefore opened a cinema in the building called the Neepawa Opera House. When Brooker complained to the Vitagraph Company of America, a Brooklyn-based studio and the largest film producer of that time, that they were sending him unworthy films to screen, they invited him to write his own scripts. Rising to the challenge, Brooker wrote and sold several detective scenarios about a Sherlock Holmes–like character, Lambert Chace. A number of his films were made and three survive.

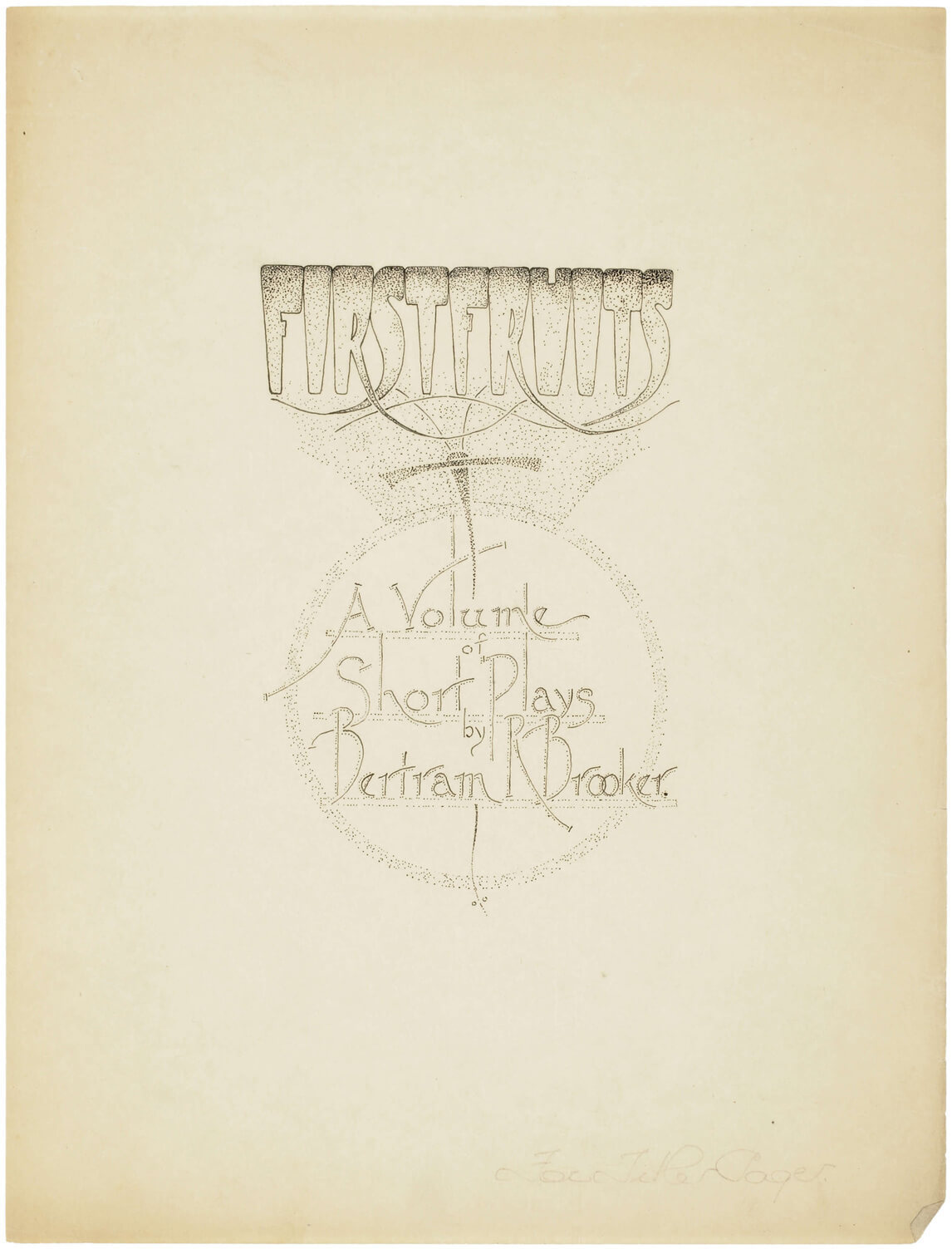

From 1911 to 1914, Brooker was active in local theatre productions in Portage and Neepawa. He directed a play called Much Ado About Something at the Portage Opera House, and he seems to have acted in a number of local productions. A newspaper notice read: “Mr. Brooker is an amateur actor of considerable ability. The characters he has sustained in several amateur productions in Portage have always been a feature of the play. As a play rite [sic] he has also some claim to distinction, his plays being eagerly sought by several moving picture producers.”

Later, in the mid-1930s, Brooker would collaborate with the avant-garde playwright and director Herman Voaden (1903–1991), who staged plays by Brooker. In theatre and cinema, Brooker saw how ideas and concepts could be brought to life.

A Newspaper Man

Brooker’s success at writing for films and local theatre inspired him to pursue journalism and newspaper layout design in Neepawa and then back in Portage la Prairie, where he returned in 1914. He became editor of the Portage Review, a local newspaper funded by the Conservative Party.

In 1913 he married Mary Aurilla (“Rill”) Porter, whom he had met when both were members of the St. Mary’s Anglican choir in Portage. Rill would later come to develop an extremely good knowledge and appreciation of her husband’s paintings and drawings. In 1915, with the First World War raging, the Brookers settled in Winnipeg, where he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Engineers, although he never went overseas. His son, Victor, was born there in 1917, and his daughter Doreen two years later. (Their youngest child, Phyllis, was born in Toronto in 1924, after the Brookers had moved there.)

Between 1919 and 1921, Brooker worked for several newspapers, first in Winnipeg (the Tribune), then in Regina (the Leader-Post), then back in Winnipeg (the Free Press). Winnipeg was one of the most prosperous cities in Canada at that time and thus an excellent place to test his growing skills in writing and design. At the Free Press he was employed in a variety of roles: promotion director, music editor, drama editor, and automobile editor. In addition, he submitted illustrations and drawings to magazines such as Collier’s.

In 1919 during the Winnipeg General Strike, one of the most confrontational events in Canadian labour history, Brooker served with the Special Constables, or “Specials”—citizens who were given the right to “disrupt” (rough up) the strikers. No evidence survives explaining why Brooker joined this group. His employer at the time, the Free Press, was firmly antagonistic to the strike, and it is possible that he was pressured at work to become a “Special.” Regardless—and contrary to the intent of the influential bankers, politicians, and the top city newspapers who had organized the Special Constables—Brooker saw his role as that of a peacemaker and he was sympathetic to those on the picket lines. His first surviving oil painting—The Miners, 1922—shows workers on the way to the pit, and suggests that Brooker possessed a strong sense of empathy for the underclass.

Advertising and a Return to Art

In 1921 Brooker and his family moved to Toronto in order for him to work at the Globe newspaper and at Marketing, the trade journal of the Canadian advertising industry. In 1924 he purchased Marketing magazine and became the periodical’s publisher and editor. In 1927 he sold Marketing back to its original owner and accepted a position at A. McKim & Co., beginning a long career in the advertising business. Two years later, he joined J.J. Gibbons advertising agency as head of the first media research and development unit in Canada. He held this post until 1936, when he moved to MacLaren Advertising, where he remained until 1955, when he retired as vice-president.

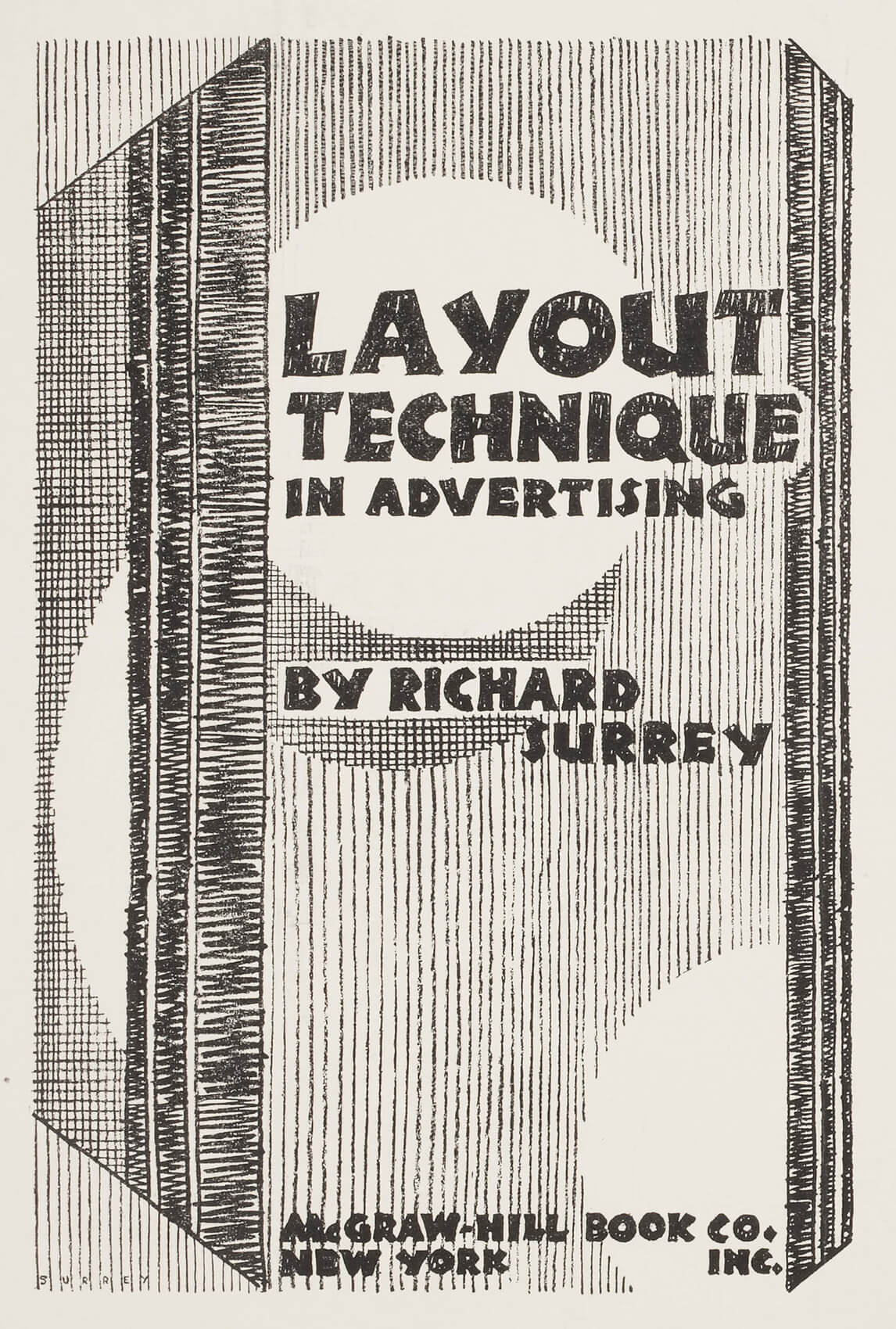

At all three firms, he spent much of his time writing advertising copy, attending management meetings, and supervising subordinates. He also began research on the psychology of advertising, investigating how a successful advertising campaign persuades consumers to buy a certain product, and he published three manuals concerned with his profession: Subconscious Selling (1923), Layout Technique in Advertising (1929) under the name Richard Surrey, and Copy Technique in Advertising (1930). During the 1920s he wrote, under fourteen different pseudonyms, seventy-seven articles on various aspects of advertising.

All the while, art also remained central. In his social life he sought out like-minded persons with a passion for art and music. The Brookers’ modest Glenview Avenue house in the middle-class neighbourhood of Lawrence Park became a meeting place for creative individuals, including the conductor Ernest MacMillan and the artists Charles Comfort (1900–1994), Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986), and Kathleen Munn (1887–1974). The University of Toronto’s Hart House String Quartet played at his home on at least one occasion.

Around 1922 to 1924 Brooker began working on a series of non-objective paintings, including various versions of Oozles. His return to visual art after what appears to be a decade of inactivity in this genre arose because of a profound mystical experience. Since the childhood soul searching that led him to paint a scene depicting the hymn “Rock of Ages,” Brooker had been intrigued by such mystical events. In 1923, during a visit to the Presbyterian church in Dwight at the Lake of Bays in Ontario, the thirty-five-year-old Brooker experienced a much more profound moment of awakening. His attention fixated on a grove near a brook and, not completely aware of what he was doing, he abandoned the church and made his way to the water. There, as he writes in his unpublished autobiographical novel, “everything became one; everything in the universe, in the world was one.” Following the experience, he coined the term “unitude” to describe this state of stillness (quietude) conjoined to a strong sense of purpose (unity). Brooker believed that the artist in society was obligated to instruct others on how to get in touch with their inner spiritual values. This mystical experience reinforced his spiritualism and motivated him to attempt to render the mystical in art.

Infused with this new sense of “cosmic consciousness,” Brooker began Oozles and Noise of a Fish, both c.1922–24, and other nonfigurative paintings in tempera that were indebted to the Vorticists, a group of English artists—inspired by Italian Futurists such as Giacomo Balla (1871–1958), David Bomberg (1890–1957), and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944)—who used abstract shapes to suggest violence and movement (see, for example, Bomberg’s The Mud Bath, 1914). Brooker adapted the style because he felt that it allowed him to express visually the mystical speculations with which he was grappling. These small works of his are extremely colourful and vivid but crudely rendered. Brooker was obviously teaching himself how to paint.

Lawren Harris and the Group of Seven

In 1923 Brooker became a member of the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir and he was admitted to the Arts and Letters Club of Toronto, where he met Lawren Harris (1885–1970) and other members of the Group of Seven. The Group had come into being in 1920 in response to what its members considered the stultifying academic painting practices of the time. Harris, Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), Frederick Varley (1881–1969), Frank Johnston (1888–1949), Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945), and A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) sought ways of capturing the distinctiveness of the Canadian landscape. They travelled to various spots in northern Ontario, as Varley put it, “to knock out of us all the preconceived ideas, emptying ourselves of everything except that nature is here in all its greatness.” Brooker was sympathetic to the Group’s nationalist agenda, but he felt that their emphasis on the wilderness was too limited and that there were many other ways of creating distinctively Canadian art.

Brooker most closely associated with Lawren Harris. The two artists had not only an interest in spiritual values but also a willingness to experiment with infusing those principles into painting. Although Brooker never joined the Theosophical Society, like Harris he shared some of the doctrine’s ideas. In a key passage in A Canadian Art Movement, Frederick Housser states, “Harris paints the Lake Superior landscape out of a devotion to the life and soul and makes it feel like the country of the soul.” Although Brooker did not object fundamentally to such a claim, he felt that as long as the influence of the Group of Seven released young Canadian painters from the stuffy ties of Victorianism, its purpose was fulfilled. However, he did not consider their paintings genuinely modern. They did not incorporate contemporary trends in European art such as can be seen in the work of Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and other avant-garde artists.

Abstract Epiphanies

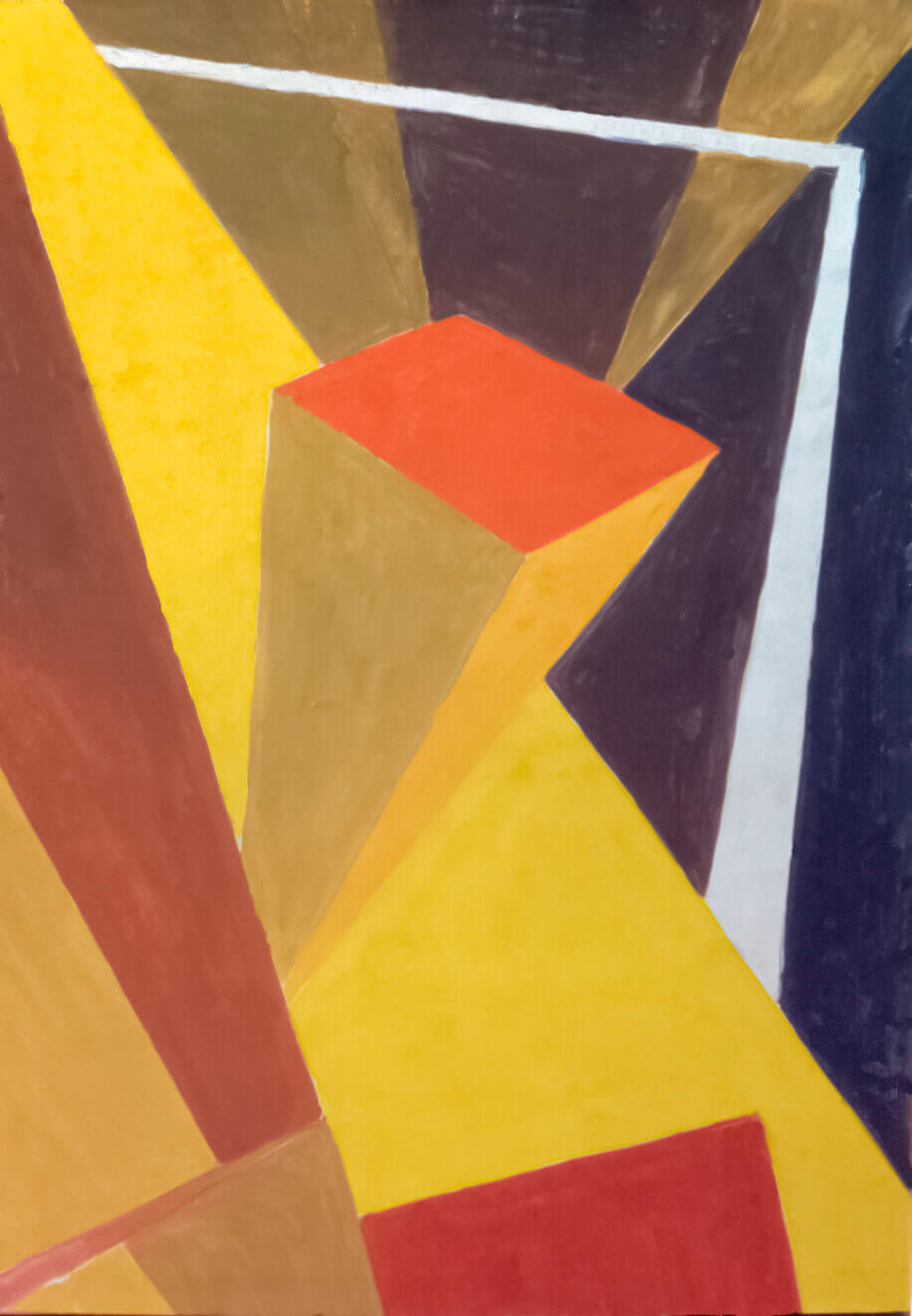

By the beginning of 1927, Brooker had moved far beyond the early abstracts of 1923 into an artistic realm that would surprise and puzzle his contemporaries. Without fanfare he had been working on a remarkable series of canvases, unlike anything previously produced by a Canadian artist—such as Sounds Assembling, 1928, with its movement and penetrating energy enhanced by geometric exactness. In large, bold, majestic abstract compositions Brooker forced his viewers to confront the possibility of a spiritual reality.

Some of these works, such as Abstraction, Music and The Way, both of 1927, demonstrate clearly how Brooker’s imagination fed off music. At this time, Brooker’s images aspired to the condition of music as manifested by some of the great composers. His taste was all-encompassing, but he favoured choral works, such as by Handel, and composers such as Beethoven and Wagner, who in large-scale compositions sought to explore humanity’s relationship with the spiritual world.

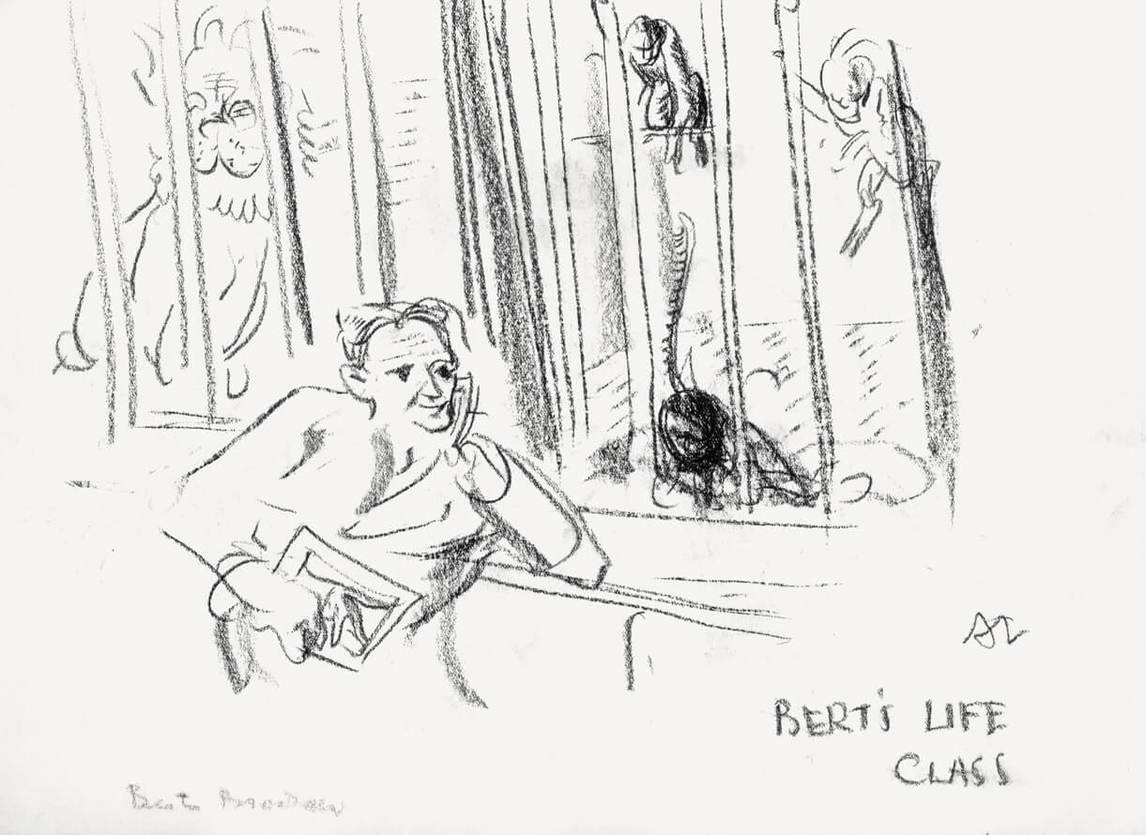

In January 1927 a selection of Brooker’s most recent abstracts were given a modest show at the Arts and Letters Club, sponsored by Lawren Harris and Arthur Lismer and widely hailed as the first solo exhibit of non-objective work in Canada. Nothing Harris had painted by then approached the level of abstraction these canvases displayed. In fact, it can be argued that Harris’s subsequent move into greater abstraction was influenced by Brooker, who told the Toronto Star that these paintings “were expressions of musical feeling.”

Gloomily, Brooker described the reaction of those who attended the show: “There was a curious silence about the place, relieved only by the whisperings of groups who would not come up and discuss [the work] with me openly.” Clearly, these radical canvases did not resonate. Worse, his work was severely criticized by J.E.H. MacDonald, who later offered a backhanded apology: “I cannot understand your process of working.” A very hurt Brooker resented the fact that his friends did not defend him: “I could not help feeling let down and rather deserted by Lismer and Lawren running away without any kind of announcement, or even notice as to whose pictures they were and what they intended to convey.”

Despite his disappointment, Brooker continued to paint. In 1928, 1930, and 1931 he participated in Group of Seven exhibitions, because the Group obviously recognized his compatibility of conviction with their aims. However, he showed only one abstract, Sounds Assembling, in 1928 and none in 1930 or 1931. The St. Lawrence, 1931, was shown in the 1931 Group of Seven exhibition. In March 1931, when eight of his abstract canvases, including Sounds Assembling and Alleluiah, 1929, were shown in a solo exhibit at Hart House in Toronto, Brooker finally felt vindicated, stating the show was “the first time I have ever seen seven or eight of my abstract paintings on a well-lighted wall together, and I got quite a thrill from it. They looked better there than I have ever seen them.”

His nonfigurative paintings from 1927 to 1931 each contain a portion of the artist’s vision. As such, they can be seen as programmatic, emphasizing an aspect of the artist’s view of life’s possibilities. Like the symphonies of Beethoven, these works, including Resolution and Ascending Forms, both c.1929, offer the artist’s philosophy of life: they are images of hope and redemption; they are also about questing for truth and about the transition between material and spiritual spheres of existence. As a unit, they remain a daring, monumental achievement.

A Turn Toward Representation

Despite his artistic accomplishments, painting remained an avocation for Brooker. He tended to think of himself—and was better known—as a writer rather than as an artist: the printed heading on his personal stationery from 1930 reads “Bertram R. Brooker * Writer * 107 Glenview Avenue, Toronto, Canada.” He earned a comfortable living in the advertising world and he never depended upon selling his art as a means of support. His wife, Rill, who devoted herself to child rearing and managing the household, protected her husband’s time in his studio on the top floor of their home.

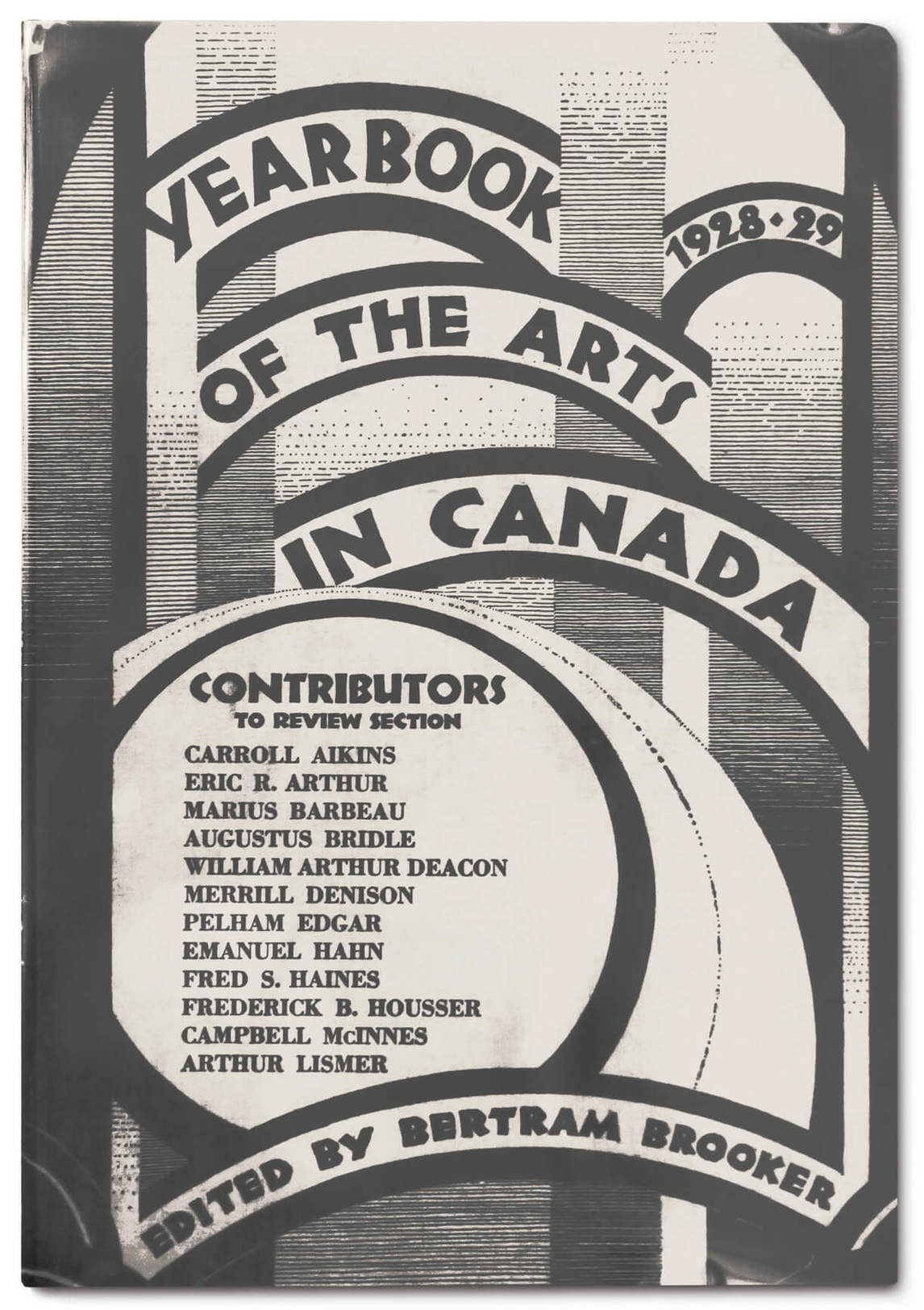

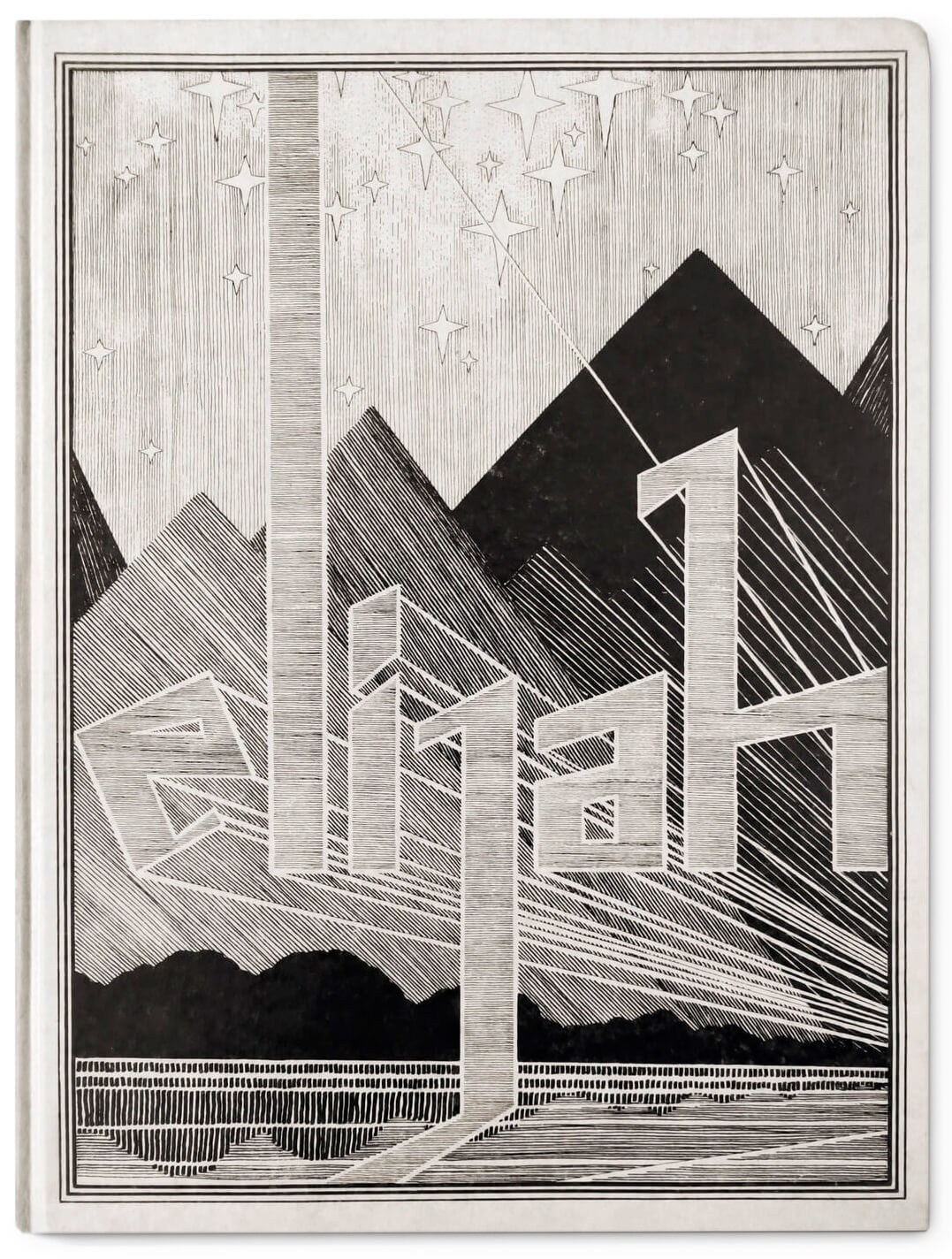

Supplementing his advertising income with work as a freelance writer, from 1928 to 1930 Brooker wrote “The Seven Arts,” a syndicated column that appeared in newspapers, including the Calgary Herald and the Ottawa Citizen, in the powerful Southam newspaper chain. In 1929 he edited an anthology devoted to artistic developments across Canada: Yearbook of the Arts in Canada (there was only one further volume, in 1936, because of economic restraints caused by the Great Depression). In the 1929 volume he proclaimed, “There is a spirit here [in Canada], a response to the new, the natural, the open, the massive—as contrasted with the old, artificial, enclosed littleness of Europe—that should eventually, when we rely on it less timidly, become actively creative.” Moreover, from 1929 Brooker investigated the possibility of publishing his ink drawings illustrating the Bible and other literary texts, but he quickly discovered that the market for such work had disappeared. Only his illustrations for Elijah (1929), made their way into print.

In both yearbooks and especially his “Seven Arts” columns, Brooker wrote about a wide variety of literary and artistic figures. Among the canonical writers were Keats, Goethe, Shakespeare, and Yeats; contemporary ones included Ernest Hemingway and Aldous Huxley. The artists, among many others, included Marcel Duchamp, Constantin Brancusi, and Henri Matisse. Writing, especially writing a syndicated newspaper column, allowed him to reach a wide audience.

But Brooker continued to paint, and in the summer of 1929, he experienced a new epiphany when he met Winnipeg artist Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956), who worked in a representational mode. His response to FitzGerald’s work was immediate and profound. For the first time in his career, he embraced a new way of painting. He continued to produce his great abstract canvases, and would do so for two more years, but various forms of representation now became his primary mode. This change in direction may have been motivated in part by the hostile reactions that had greeted his nonfigurative paintings, but the alteration is more fundamental than that. By the summer of 1929, he had taken what he wanted from the various nonfigurative European and American modernisms and was ready for something new.

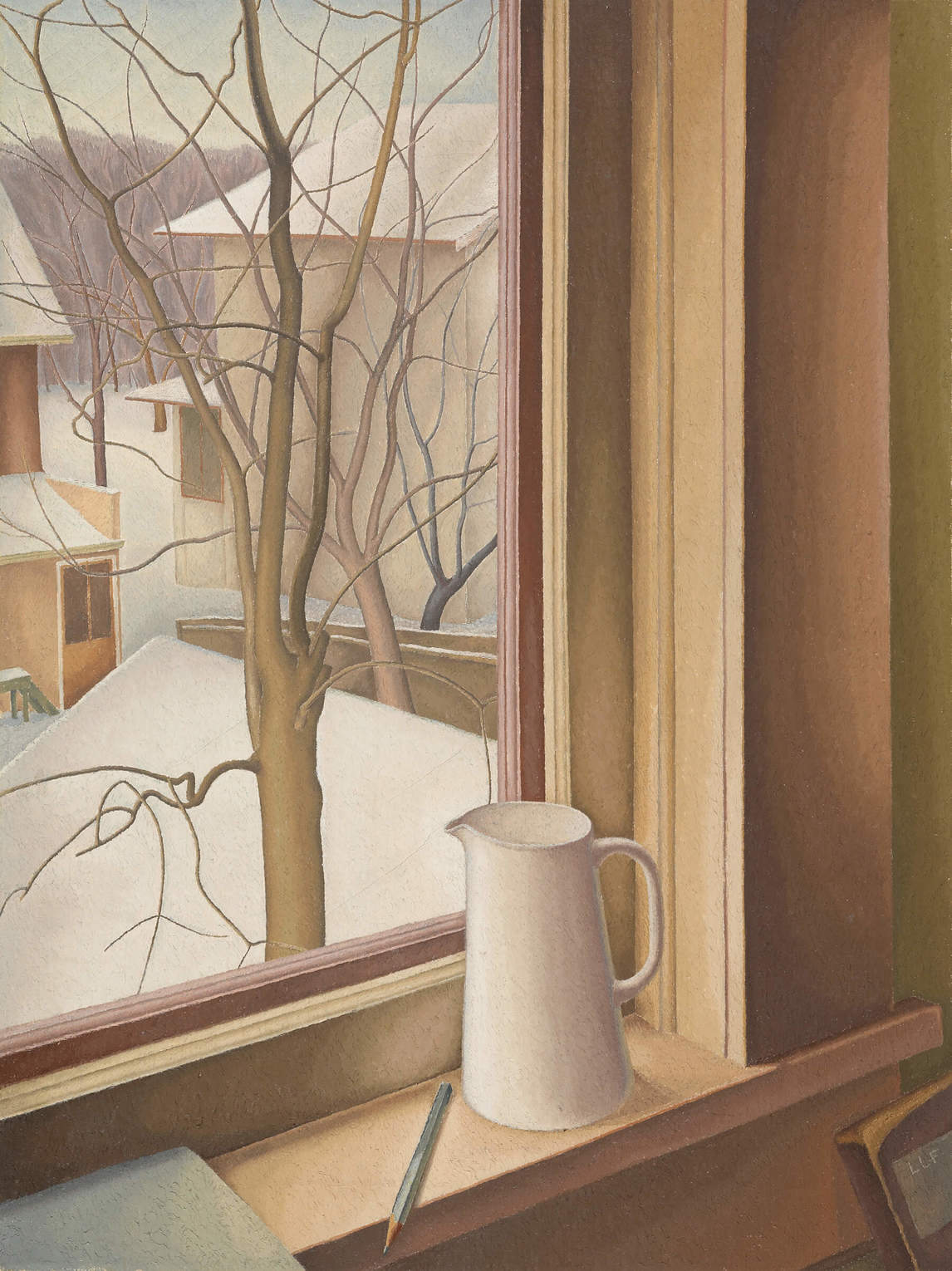

Unlike Brooker’s relationship with Lawren Harris, his friendship with FitzGerald was straightforward. FitzGerald’s landscapes and still lifes, as in Doc Snyder’s House, 1931, and From an Upstairs Window, Winter, c.1950–51, were drawn from his immediate surroundings. FitzGerald was always careful to depict the essence of what he saw in nature. He used close observation to extract what could be labelled the kernel of the subject. He wanted to capture the living form of an object, the truth lying beneath an object’s outward form—he pared down his landscapes to essentials and in this way introduced elements of abstraction into his work.

This synthesis of abstract and representational elements is what Brooker immediately recognized in FitzGerald, and a deep empathy developed between them. Brooker saw FitzGerald’s approach as a way of expanding his own previous stylistic repertoire without betraying his bedrock artistic principles. On December 28, 1929, soon after meeting FitzGerald, Brooker wrote to him to say that, under his influence, his art had moved in a dramatically new direction. This change can be readily seen in Manitoba Willows, c.1929–31, and Snow Fugue, 1930. For the remainder of his artistic career, Brooker experimented with various approaches: some abstract work, some representational but most combining the two modes. The loosening of his ties to abstract art must have motivated him to try his hand in a number of traditional genres, such as the nude and, later, still lifes and portraits—and even sculpture.

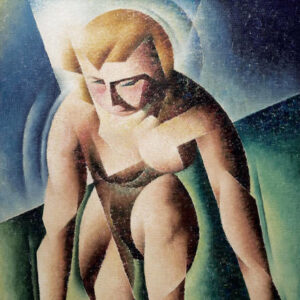

In March 1931, the Ontario Society of Artists accepted Brooker’s Figures in a Landscape, 1931, for its annual exhibition. The painting shows back views of two female nudes in an outdoor setting. Officials from the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario), where the exhibition was held, removed it from the show and from the catalogue. The stated reason: impropriety. An indignant Brooker responded with the essay “Nudes and Prudes.” In it, he argued that the prudery in response to images of the nude arose in large part because elders in society did not wish the young to be corrupted by public displays of nakedness.

In November 1931, Brooker attended the 30th International Exhibition of Paintings at the Carnegie Institute (now Carnegie Museums) in Pittsburgh. There he was amazed by “the tremendous preponderance of figure painting in all of the countries represented.” Doubtless, he came to the conclusion that his recent move toward representation was one that followed contemporary trends.

In addition to FitzGerald, Brooker’s friend Kathleen Munn supported his art during the 1930s. This fellow Toronto artist also experimented with mixing modes of expression, in her case combining Cubism and figuration. As early as 1916, Munn had incorporated abstract elements into her representational compositions. Brooker exhibited such paintings before she did, although it is possible that her practice enhanced his rather than the other way around. Brooker especially liked the musicality he discerned in her work and purchased Composition (Horses), c.1927, and Composition (Reclining Nude), c.1926–28.

A Man of Many Parts

By the early 1930s, Brooker was well connected with other members of the Canadian art scene, most notably as one of the founding members of the Canadian Group of Painters (CGP). The CGP was formed in 1933 and in many ways extended and refined the nationalist agenda of the Group of Seven, which had disbanded the same year the CGP was formed. The CGP believed that Canadian artists had the potential to show how disparate individuals could join together to make a strong, cohesive whole. Brooker embraced this notion of community and became the apologist for this initiative by publicizing it in his writings. Four years before the formation of the CGP, Brooker had written about this topic in his essay “When We Awake!” in the Yearbook of the Arts in Canada 1928–1929. There, he tried to define what Canadian art had established and what work remained to be done:

But we are not really awake, we are not sensible of national unity and we are not sensible of universal unity. Yet there are signs that both may perhaps blossom into being. These signs, so far, are deducible only from the occasional work of isolated individuals. But the opportunities to build an art here and an audience that may be stirred by it are as great as have ever existed in any nation, if not greater.

Despite his prominence in art circles, Brooker never actively promoted his own work to museums, dealers, and collectors, nor was he represented by a dealer, and during his lifetime much of his work remained unsold. The few paintings he did sell included Dentonia Park, 1931, to Harry and Ruth Tovell, and a 1932 portrait of Morley Callaghan to the sitter. From the 1930s to the end of his life, Brooker continued his painterly experiments of combining abstract and representational elements, as in Pharaoh’s Daughter, 1950. In this painting, the countenance of the woman is discernible, but she is awash in a sea of abstract shapes.

Brooker, in middle age, dedicated considerable creative energy to literature as well as to visual art and advertising. In 1936 he published the novel Think of the Earth, which won the first Lord Tweedsmuir Award (renamed the Governor General’s Award in 1957) for fiction. Under the pseudonym of Huxley Herne he published another novel, The Tangled Miracle, a Mystery, in 1936, and a third, The Robber, under his own name, in 1949. The manuscripts of other, unpublished novels exist; there are more than sixty extant short stories, complete or in various states of completion; he also wrote many poems unpublished in his lifetime.

Sometime in 1954, Brooker’s health declined. A few months before he passed away, Brooker retired from his job in advertising. He died on March 22, 1955. He was a prodigiously talented man of indomitable energy who worked on his art and on his writing almost to the very end of his life. His creativity took him in many directions—those of playwright, screenwriter, actor, copywriter, artist, short story writer, novelist, essayist—as he strove to communicate his spiritual vision.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements