Annie Pootoogook worked in a unique style of art that remained unmistakable throughout her short career. She actively pursued drawing for about ten years, though she also created works during her later life. She remained committed to a drawing practice that employed felt tip pen, pencil, and coloured pencil to create narrative, direct, and often understated compositions. Although she did experiment with large-scale papers, she preferred to work with smaller sheets of 51 x 66 cm. Yet regardless of what size Annie chose to make her compositions, they always had a tremendous impact.

Critical Materials and Early Influences

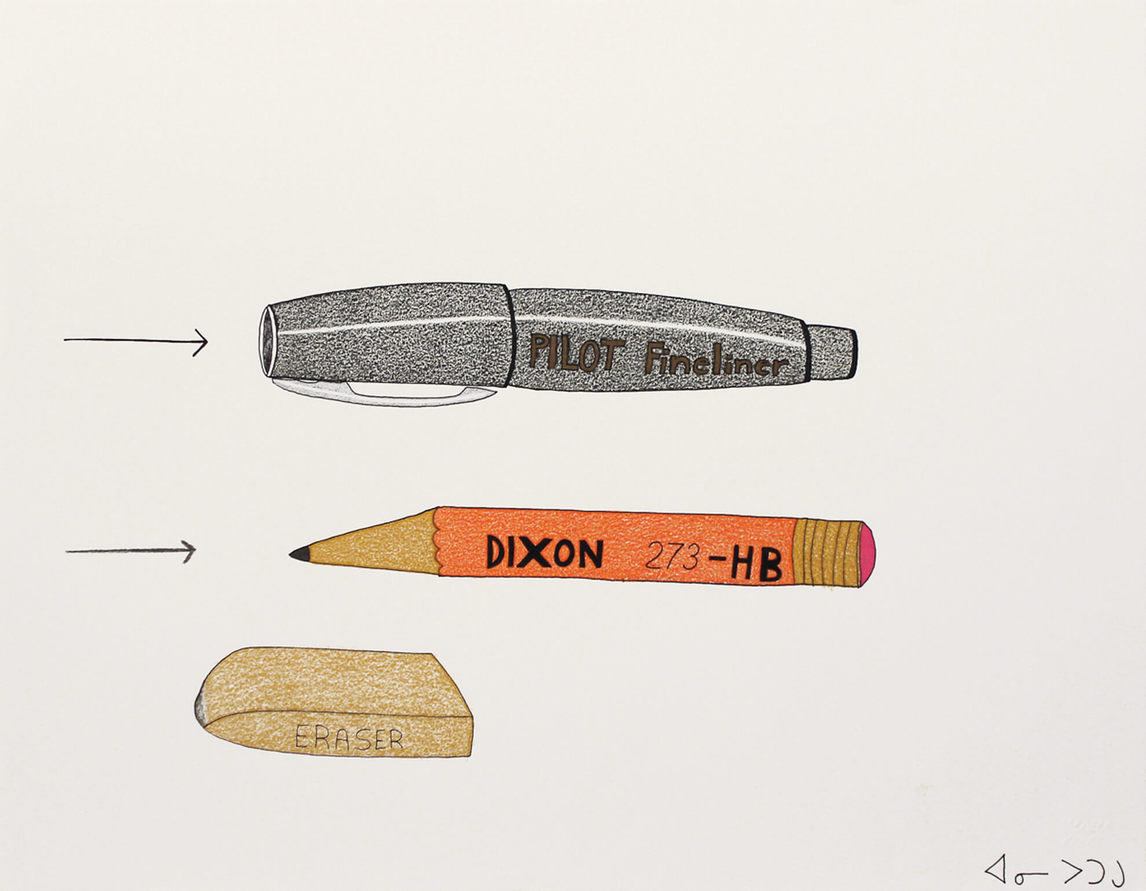

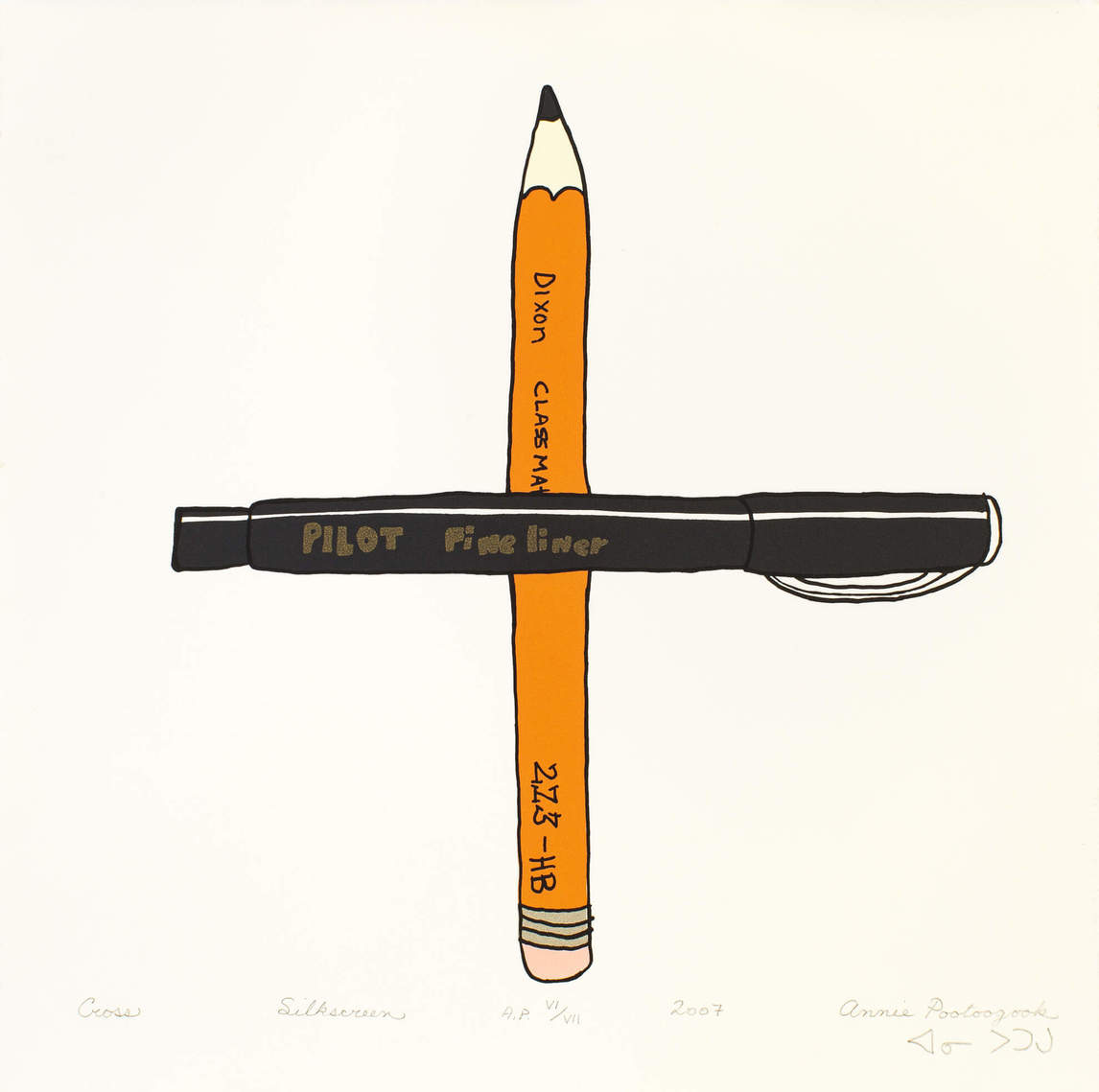

In her practice, Annie Pootoogook made use of felt tip pens, graphite, pencil crayons, and paper. The varied styles and techniques of her early works, such as Eating Seal at Home, 2001, and Composition (Family Playing Cards), 2000–2001, demonstrate her willingness to experiment and learn. Annie quickly developed a technical command of the drawing medium. Drawing on paper is a long-held tradition in the North, begun in the 1950s and originally practised by what is known as the first generation, which includes notable artists such as Annie’s grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona (c.1904–1983) and Pudlo Pudlat (1916–1992).

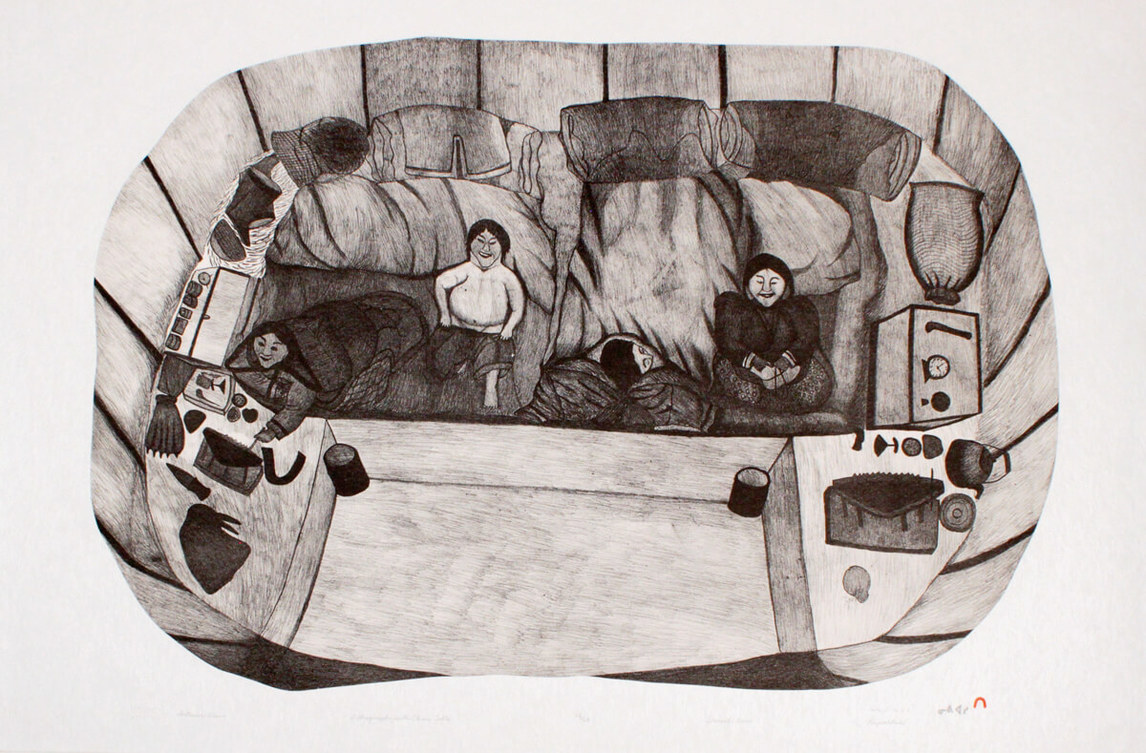

Although her use of line is similar to that of many of her predecessors, including her grandmother and her mother, Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), Annie’s mature compositions are very different from those of earlier Inuit artists. In the works of artists such as Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013) and Mayoreak Ashoona (b.1946), images of mythic animals dominate the paper. Annie is known for her interior spaces, which she defines by walls and floors, and sometimes a door and windows. She typically fills the room with a clutter of furnishings and mundane objects. The people in her interiors take up the space as people tend to do—they arrange themselves comfortably and naturally. When she shows an isolated object, such as a pair of glasses or a bra, it shows up boldly, like an icon against the expanse of paper. Although Annie’s predecessors did not typically compose interiors or isolate objects in the same way that Annie did, certain works, specifically works by Napachie, are recognized as important precedents.

Napachie’s influence on Annie’s work can be seen in works like Interior View, 2000. No doubt Annie had watched her mother create drawings during her younger years; traces of Napachie’s descriptive compositions, which include the minutiae of daily life, are visible in Annie’s later creations. Direct correlations between the two artists’ works can also be found. For example, Napachie’s Trading Women for Supplies, 1997–98, is a drawing that portrays the darker subject matter of gender-based exploitation. Annie too created works, such as A True Story, 2006, that depict disturbing real-life occurrences drawn from her community. Napachie’s struggles with mental health and abuse influenced Annie’s art as well. After watching her mother make drawings about these difficult experiences, Annie went on to create her own, including Man Abusing His Partner, 2002, and Memory of My Life: Breaking Bottles, 2001–2. More broadly, both Annie and her mother were inspired by memories of their childhoods.

Annie spent time as a young girl watching her bedridden grandmother, Pitseolak, draw. We see Pitseolak’s influence in Annie’s strong lines and also, in subtle ways, in some of Annie’s subject matter. For example, Pitseolak’s signature black-framed glasses appear in numerous drawings, revealing the bond between the two. Annie also drew her grandmother’s portrait.

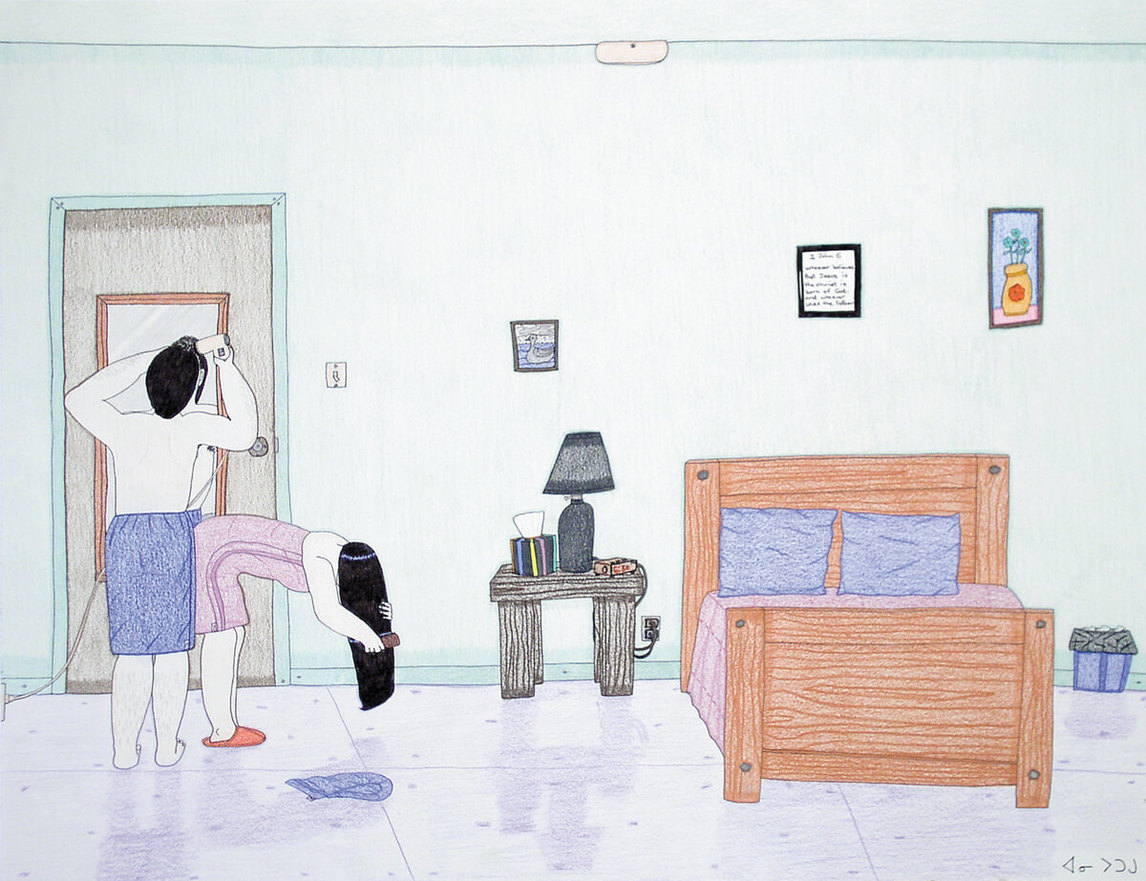

Annie produced art prolifically during her time at Kinngait Studios, developing her original take on contemporary life in the North with the support of the studio’s staff, especially William (Bill) Ritchie, who encouraged her to push herself. Annie chose to draw the realities of her North: domestic interiors, consumer products, and fragments of her own life as a young woman, experiences that are referenced in works such as Morning Routine, 2003. Art dealer and curator Patricia Feheley writes that “Annie’s narrative tendencies, meticulous draftsmanship and contemporary subject matter stand out against a half-century of graphics preoccupied primarily with issues of design and colour.”

Line, Perspective, and Colour Experiments

Annie approached each one of her drawings systematically, beginning with outlines in graphite before working up details in Fineliner and finishing with increasingly bold areas of coloured pencil. Her earlier works reveal a more tentative use of pencil crayon with less saturated hues and a lighter touch. Later works show confidence in her colour sense, with strokes that are deliberate, bright, and hard. Similarly, her earlier works were rendered in two dimensions with pencil and Fineliner, but increasingly she experimented with colour, shading, and shadows, and with the presentation of a more three-dimensional view.

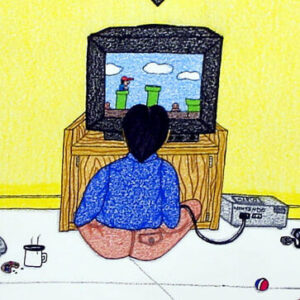

It is common for artists to begin working in black and white, a practice through which they start to establish their particular styles. In Annie’s case she began incorporating colour early on, demonstrating a strong sense of its possibilities. She made limited use of three-point perspective, although her handling of this technique improved as she gained experience. Her progress can be seen by comparing an early work such as Eating Seal at Home, 2001, with Composition: Watching Porn on Television, 2005, with its development of a foreground, middle ground, and background. Annie is best known for her interiors that depict daily life and routine activities, including getting ready for a date, eating country food (the traditional Inuit diet of things either caught or collected from the land), watching television, or playing cards. Her interiors show much experimentation. Some, like Dr. Phil, 2006, are densely coloured, while others use techniques suggesting perspective and depth to show a room beyond a door.

Throughout her short career Annie carried on the practice of drawing with pencil crayon, as her grandmother and mother had done. Her early drawings, such as Untitled (Women Sewing), 2004, are executed in graphite and felt tip pen. A number of drawings show a restrained use of coloured pencil; in Composition (Family Portrait), 2005–6, she cleverly inserts a thin red hairband and three pairs of delicate pink lips into a composition dominated by flat black forms and strong, thin black lines on a white surface. In some earlier works, her pencil work appears more cautious. This approach may have been intentional, but most likely as her confidence in image-making improved she began to feel more comfortable using colour. As she progressed, it became evident that her colour sense was exceptional; her mastery is shown in the bold strokes of colour that saturate the paper of her mature work. In Holding Boots, 2004, a work that plays with flat surfaces and implied perspective, she uses the complements of green in the woman’s socks to ground the drawing between the crouching red knees.

In some later works, Annie used marker, paint, and oil stick to achieve new, experimental effects. In 2007, while she was living in Montreal, she was introduced to oil stick by Paul Machnik at Studio PM. This new medium remained an experiment for Annie and she did not prioritize it in the same way she did coloured pencil, graphite, and ink. However, she did produce a number of works with oil stick, most significantly (Composition) Drawing of My Grandmother’s Glasses, 2007, a large, vibrantly coloured drawing of her grandmother’s immediately recognizable black-framed glasses. It was awarded a purchase prize by the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, at Art Toronto, an international art fair, in 2007.

Composition in the Sulijuk Tradition

Compositionally, Annie’s work is within the sulijuk tradition (translated as “true” or “real”). This practice is a mode of working seen in the North and the approach encouraged at Kinngait Studios. Much has changed, though, since Annie’s predecessors began drawing their experiences of living on the land; in composing images of a far different North, Annie too was drawing her own lived and true reality. She depicted life as she saw it, revealing a reality that, to outsiders with little knowledge of the North, appeared to be at odds with the traditional outdoor scenes that people in Southern Canada had come to expect in Inuit artists’ works on paper. This honesty is the source of Annie’s originality.

The timing of Annie’s arrival on the scene is also important. Kinngait artists were starting to produce drawings that were being recognized as finished artworks. The drawing medium gave Annie the freedom to develop the subjects of her own lived reality—she did not have to yield to the expectation that her drawings were preparatory works for the production of prints, a medium that still held traditional associations. Although Annie’s work was included in some Cape Dorset Annual Print Collections, it was her drawings that were sought after in the market.

At the beginning of her career, Annie drew many small interior and camp scenes, but as she developed her skills as an artist she alternated freely among different compositional schemes. These include interiors of homes, objects taken from those interiors and displayed in isolation, vignettes of life on the land, and images centred on the page and encompassed by sinuous lines. Her process was meticulous, requiring great concentration to execute her finished works.

The simple graphic style that came to characterize Annie’s art was at first controversial among curators and collectors alike, yet it proved to be immensely popular, especially among supporters of contemporary art. Some people condescendingly commented that a child could accomplish similar work or that it appeared naive. This type of criticism is nothing new; it has been a consistent reaction to modern and contemporary art for over a century. However, with respect to Annie it held little credence. She was talented and hard-working; she honed her drawing skills by working diligently, employing the lessons of Elders while seeking to set herself apart from her peers. The originality of her work speaks to her commitment, vision, and skill.

Narrative Realism

Annie’s most recognized and documented drawings are in the tradition of narrative realism. They tell stories or document her life. Her drawings depict life as she experienced it in Kinngait, from eating meals and watching television to playing games or having sex. Her domestic interiors, for which she is best known, are often a compilation of many real homes and in these scenes we see familiar motifs, such as the same coffee mug, clock, or artwork repeated in different interiors. For example, a distinct coffee mug with a flower on it can be seen in both Tea Time, Cape Dorset, 2003, and Ritz Crackers, 2004. These motifs taken from everyday life set the stage in the present, not in a distant past.

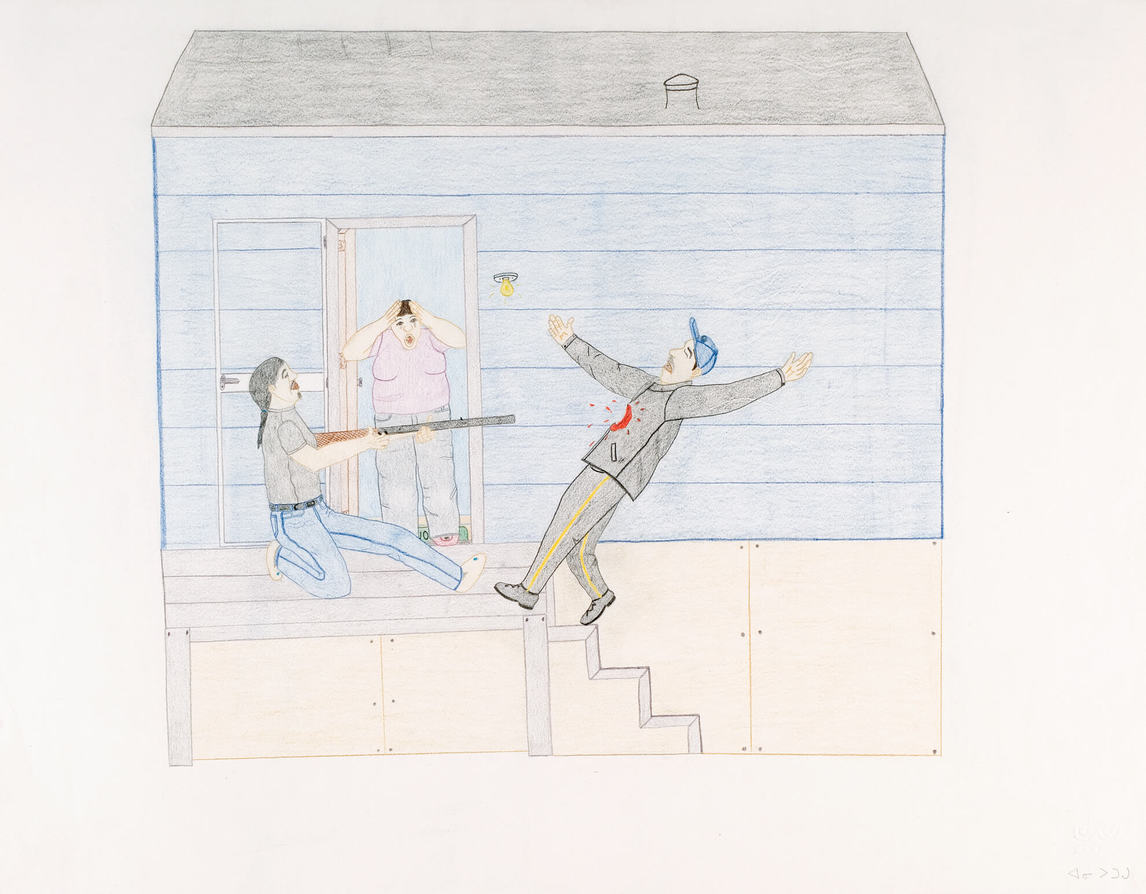

Through the techniques of narrative realism Annie was determined to reveal some of the difficult social, economic, and physical realities of today’s North. She delves into her personal struggles with domestic violence in Man Abusing His Partner, 2002, and the problem of addiction in Memory of My Life: Breaking Bottles, 2001–2. Shooting a Mountie, 2001, documents the tragic murder of RCMP Constable Jurgen Seewald in Kinngait in 2001. Similarly, in A True Story, 2006, Annie recalls from memory an accident at sea in 1979 when Special Constable Ningoseak Etidloi drowned on patrol with Constable Gordon Brooks when their twenty-four-foot-long freighter canoe capsized in rough conditions on the Arctic Ocean. It is said that the officers were setting off to find Kuiga (Kiugak) Ashoona (1933–2014), Annie’s uncle, who was at their outpost camp, and they planned to do some walrus hunting on the way. Here the different stories are conflated in a single image that shows the drowning, complete with flailing bodies and a broken canoe, the walrus hunt, and the search for her uncle all collapsed into one scene.

The acknowledgment of difficult issues recalls the later work of Annie’s mother, Napachie Pootoogook, who depicted the hardships of her community and her own life in some of her work. Many of these works document the transition period of the 1960s and the Inuit moving into and living in government-built settlements. Napachie began to draw upon episodes from her personal life, and sometimes scenes of abuse, in 1996, and continued to do so until her death six years later. Some of these works were shown in Three Women, Three Generations: Drawings by Pitseolak Ashoona, Napatchie [sic] Pootoogook and Shuvinai Ashoona, an exhibition held at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario, and the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1999. Only a few years later, Annie’s own similar drawings became her most iconic pictures.

Elder Jimmy Manning said in an interview in 2005 that “Annie’s work is, like, today and yesterday… daily happenings, shopping, music, the feast.” But Manning has also said: “Sometimes she will draw hurting feelings from her heart which she’s not afraid to say on paper.”

Psychological Drawings

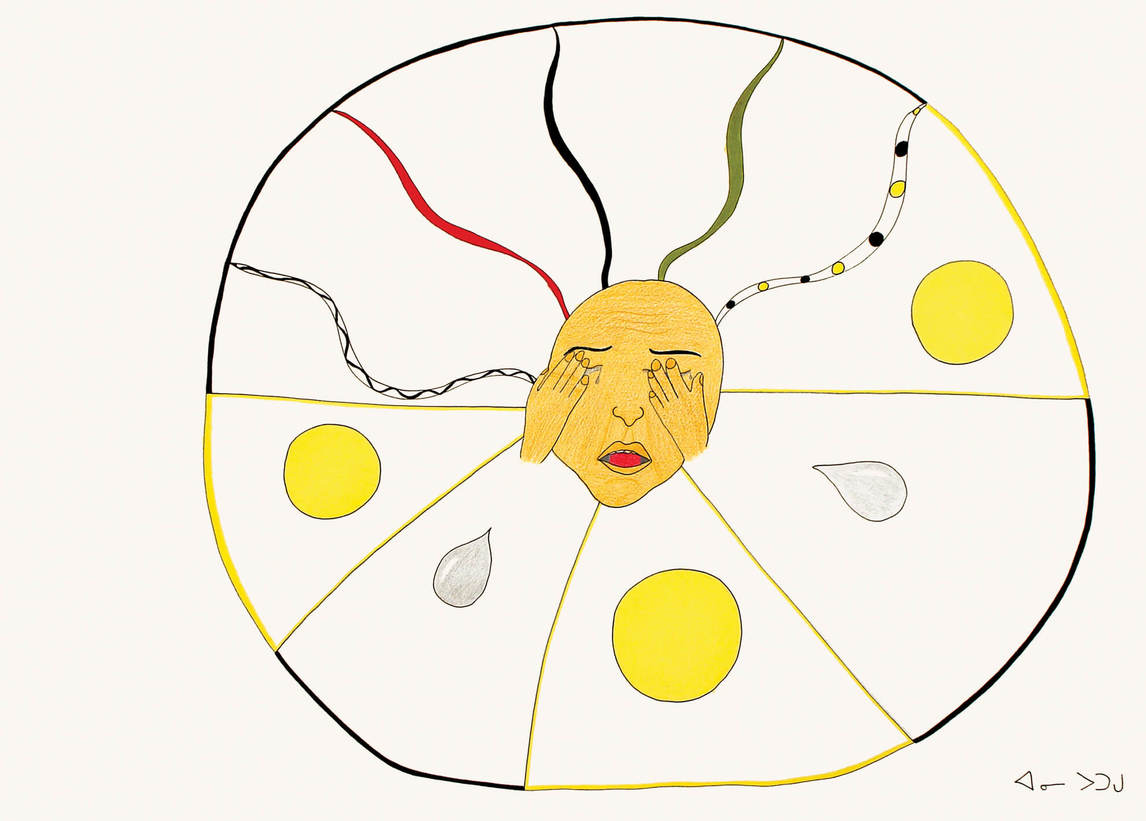

Caoimhe Morgan-Feir writes that while Annie’s interior and exterior scenes function like stages, with rectangular regions where actions take place, the drawings that are interior to herself—her “psychological drawings”—are notable for their sinuous lines encircling a central image that often seems to float on the page. One such image is Composition (Evil Spirit), 2003–4, where, writes Morgan-Feir, “an umbilical cord-like line connects the figure’s mouth to the genitals of the spirit, encircling them both.” In many of these drawings, Morgan-Feir observes, “the central figures sit in the middle of the page, with elements reaching in and looping out. There are some formal similarities with her other scenes—namely, her strong, clear lines, which she marked in pencil before rendering in ink.”

An illustration of this style is Composition (Sadness and Relief for My Brother), 2006. Annie began this work in Scotland, where she spent two months participating in the Glenfiddich Artists in Residence program. Patricia Feheley interviewed Annie extensively about her work, and they discussed this drawing. Feheley recalls, “She had started a drawing and there were all of these black lines and things…. And she said, ‘I’m drawing this because I’m upset about my brother, because he was arrested, and I think this time they’re going to put him in jail.’ But the next day, she talked to her family again and he hadn’t been jailed, he had been let go, and she completed the drawing in happy mode.”

This exchange helps explain the complexities of Annie’s technique: the curving lines, red dots, yellow dots, and stars she included in some of these works are a guide to her psychological state during the act of creating. She developed these motifs as a way to code her emotions onto the page. Some of the psychological drawings are the result of complicated entanglements with realities of the North, the influence of Kinngait Studios, Annie’s own interior battles, and her struggles to find her place in the world.

Large-Scale Works

Annie produced works in a larger format than was customary at Kinngait Studios. Although larger papers had been used in the studios in the past, there was never a market for this format before Annie tried her hand at it. Inuit art before the early 2000s was primarily marketed for private collectors rather than public museums and galleries, and smaller sizes were common. Annie’s 2006 exhibition at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto, offered a new opportunity to exhibit large-scale drawings. Typically, contemporary art museums demand larger works to create an impact in their enormous rooms, a requirement which has prompted many artists to push the boundaries of scale. Cape Dorset Freezer, 2005, was the first major large-scale piece Annie produced. For this drawing she was given a large sheet of paper, which she began to work on in the studio but eventually finished at home. Annie chose for her subject a new wall-length freezer that had been recently installed at a store in Kinngait. In the sulijuk tradition, Annie meticulously rendered the contents of the freezer and the shoppers in the store. This drawing was a tour de force and was immediately purchased by the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Cape Dorset Freezer marked a significant change in scale for drawings from artists in Kinngait. This precedent (not strictly an innovation—it had been tried before in the North) spread throughout the studios. Artists followed Annie’s example with enthusiasm, as these larger works commanded higher prices. Annie, however, remained comfortable with the smaller scale—Freezer was the largest drawing she ever created. She preferred the freedom to work quickly and move easily from one image to another. Other artists, though, such as Annie’s cousin Shuvinai Ashoona (b.1961), have taken up large-scale works in exciting new ways.

Printmaking

Although Annie is most renowned for her drawings, from 2003 to 2008 her drawings served as source material for the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection, which featured eight of her prints. Because Annie’s career as an artist was brief, so too were her print production runs for the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative.

Since 1959 Kinngait Studios has been respected internationally for its release of the Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection. It maintains its commitment to high-quality print production, exquisite stonecut prints, etchings, lithographs, and collagraphs, and to nurturing a secure and committed collector base. The studios actively foster local talent, and artists from Kinngait have continued to dominate the Inuit art market. The strategic planning at the senior management level of the Co-op has made an important contribution to its success. In addition to its first manager, James Houston, another manager, Terrence Ryan, was critical to the Co-op’s stability. Ryan, who had a solid background in the arts, served for forty years as the general manager of the Co-op and did much to support the development of the community’s arts sector while maintaining a strong and vibrant Co-op. Under Ryan’s leadership, the arts flourished in Kinngait and the Co-op concentrated on developing and expanding artists’ techniques and visual vocabularies. Following Ryan, William (Bill) Ritchie became the studio manager, and he has nurtured and supported the artists and encouraged emerging artists to spend time in the studios and experiment.

Just as Annie was viewed by some of her peers at the Co-op as something of a dissident for her drawings (although the Co-op staff encouraged her), so her contributions to the print release were also notably experimental. The studio adapted works representing her unique vision of the new North. Briefcase, 2005, and 35/36, 2006, images of men’s briefs and a bra, were definitely outside the box of customary prints. Other prints, such as The Homecoming, 2006, and Interior and Exterior, 2003, are more sentimental—they focus on Annie’s love of community. Although Annie’s prints are successful in sales and distribution, her drawings hold the art world’s attention with the sheer scope of her vision, her prolific output, and the startling directness of her imagery and composition.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements