Annie Pootoogook came of age at a time when the North and its people were being flooded by the products and media of a consumer society, and she chose to reflect this reality in her art. Her drawings depict her life as part of a world in transition, a world that respects its past while negotiating an uncertain future. By confronting prevailing expectations regarding Inuit art and refusing to cling to accepted regional and ethnic subjects and styles, Annie challenged the definition of contemporary art and changed the way Inuit art is received. Only a few artists have profoundly affected the way art is understood in Canada: Annie is one of them.

A New Vision for Inuit Art

Early in her career, Annie Pootoogook was supported by fellow artists at the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative (whose artistic division is now known as Kinngait Studios), but they also warned that her drawings might never sell. Her experimentation with subject matter expanded upon the work of her mother, Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), whose art was similarly wide ranging and included several works that confronted difficult social issues. For Annie, it was a gamble to depict contemporary subject matter based on her own experiences and to make works that might not sell and provide the income she needed. Inuit art historian Heather Igloliorte writes of the predicament facing Inuit artists: “While all around them their culture was being debased, devalued, and actively oppressed by the dual forces of colonialism and Christianity, these same values were revered, celebrated, and voraciously collected in their arts.” Annie leapt past this predicament when she created a body of work that curators recognized as unusually contemporary, and collectors and museums bought her drawings eagerly.

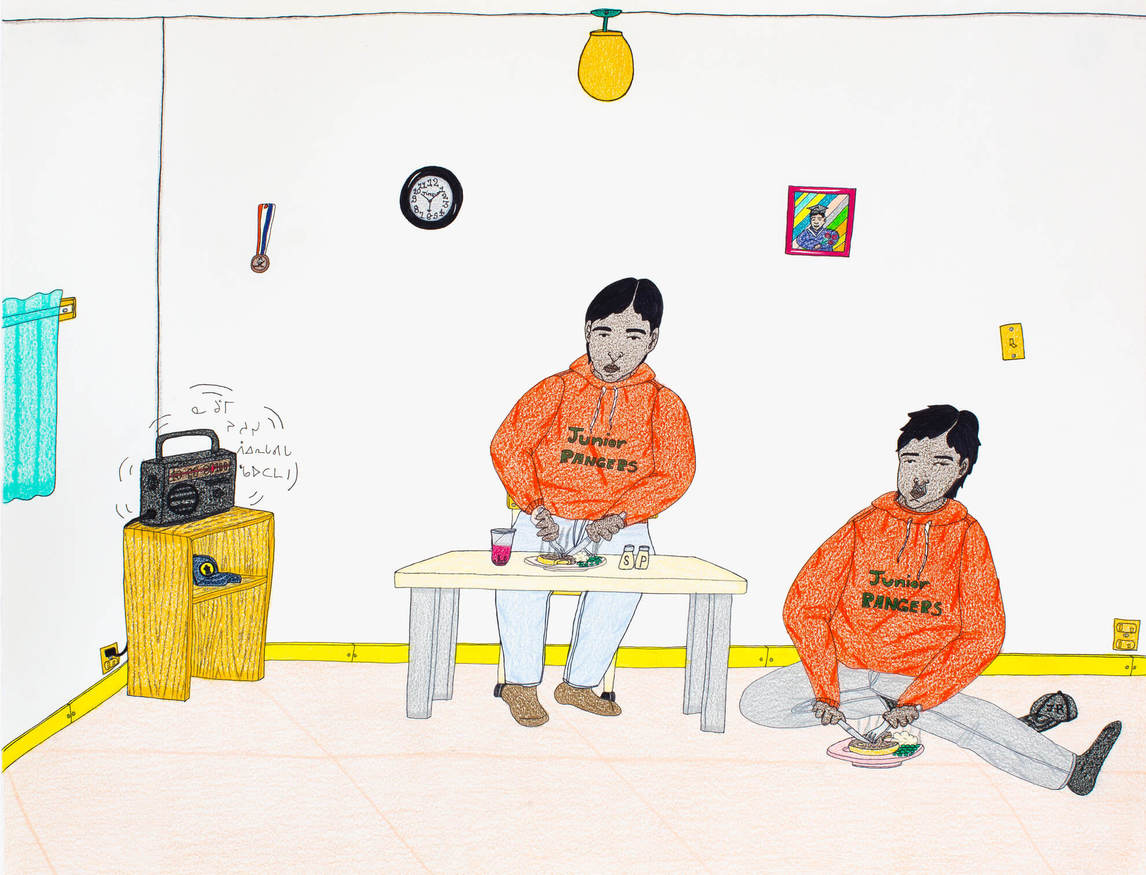

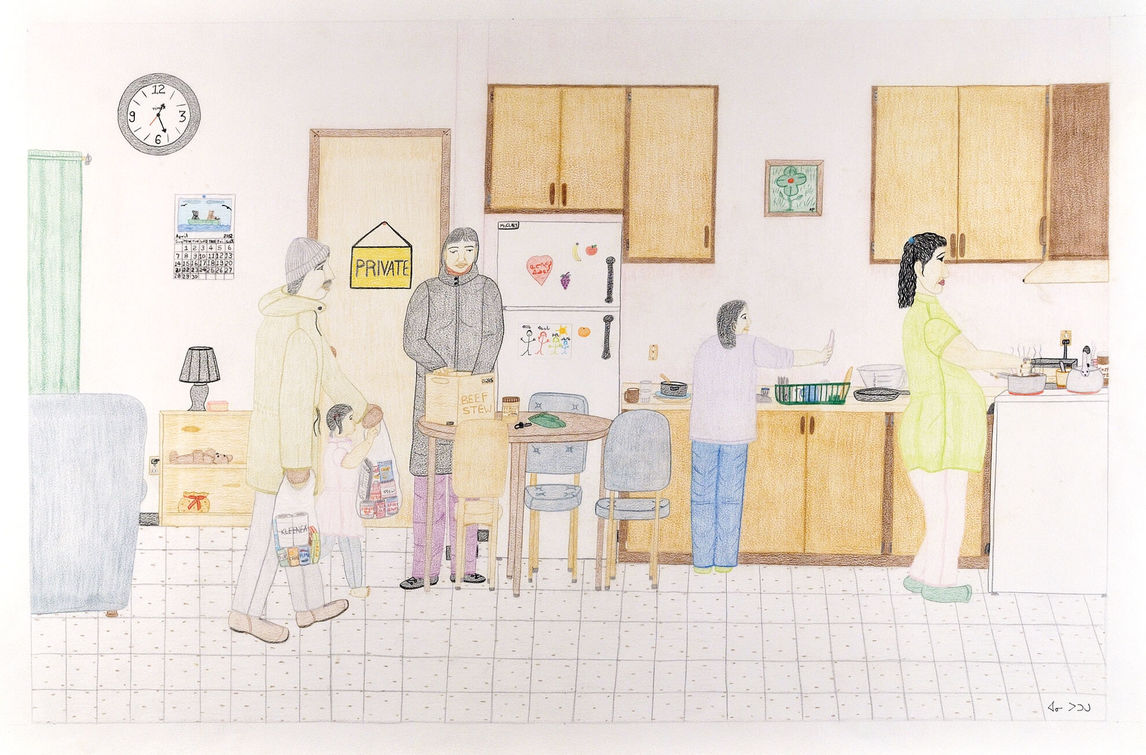

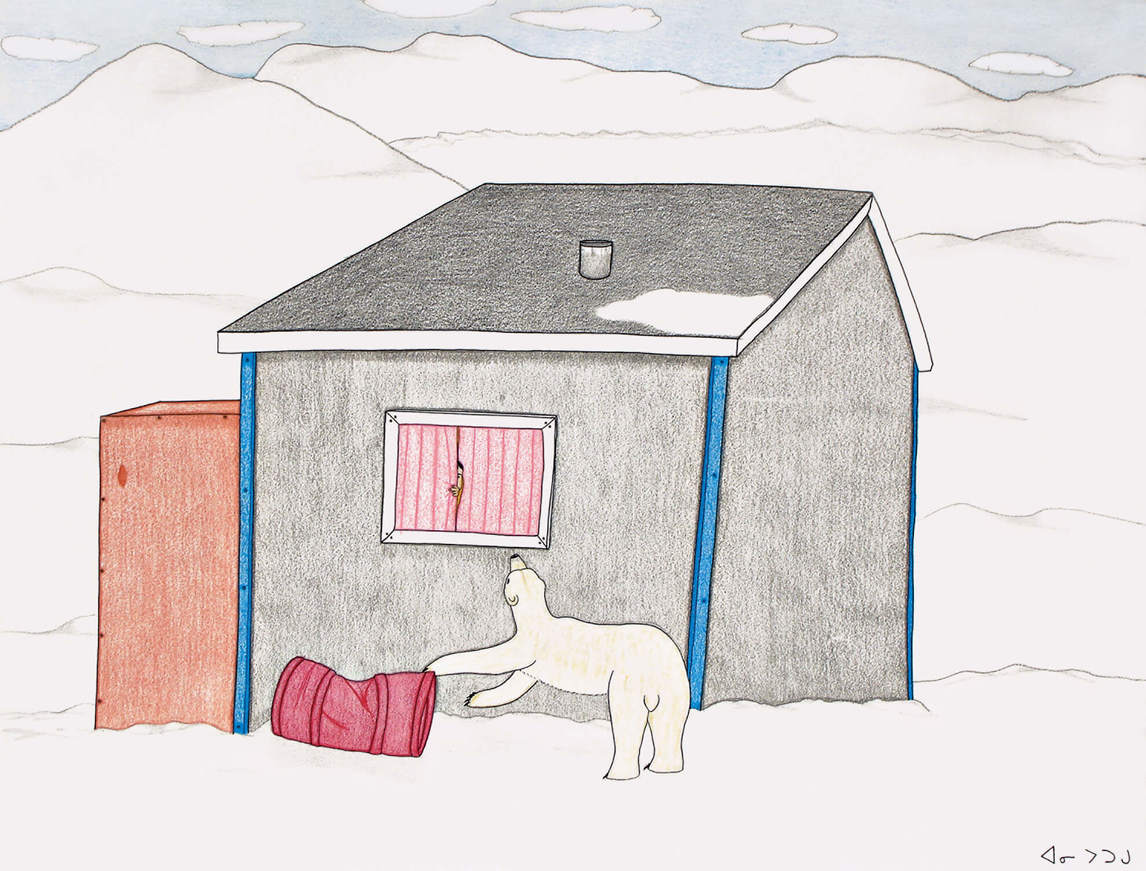

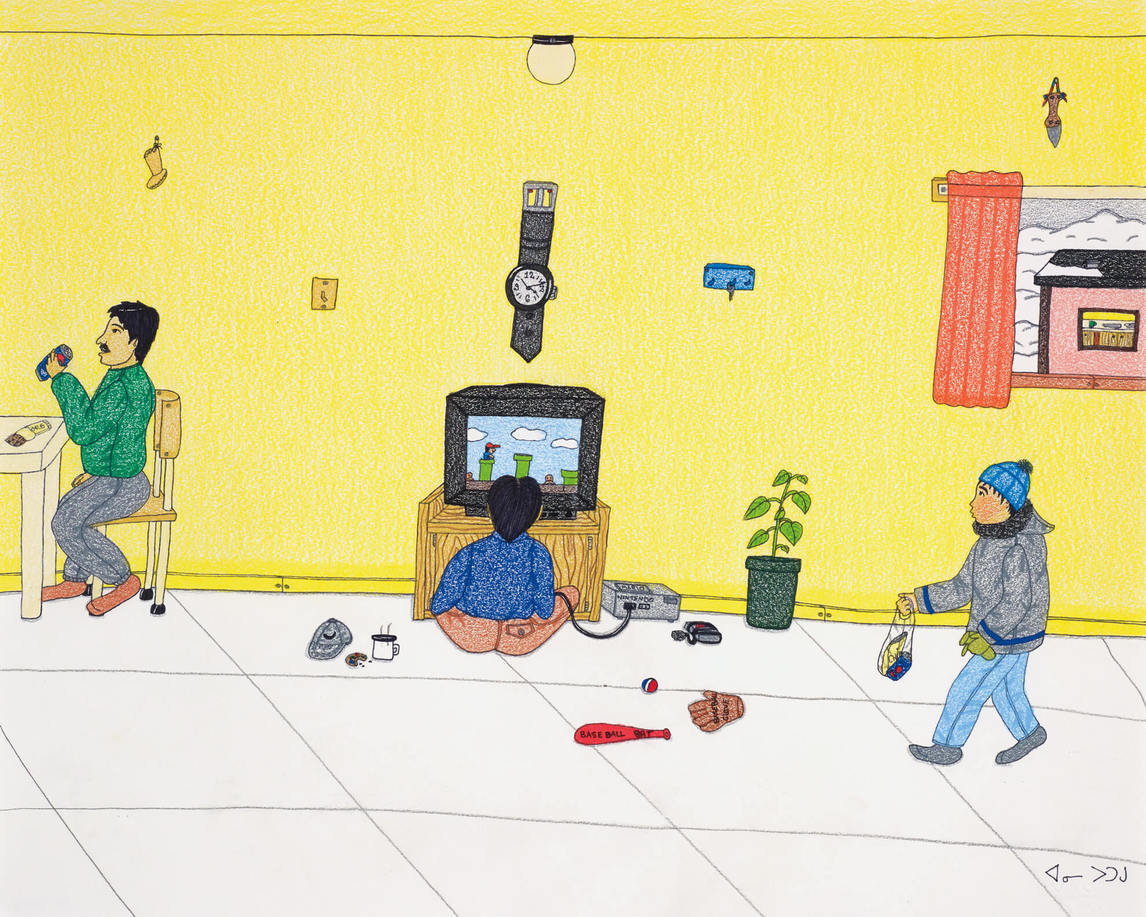

Annie holds a unique place in the history of Inuit art and within Canadian art history. Her work represents a fresh perspective on and distinct vision within her community. By the time she came of age, the community of Kinngait and the lives of its people were rapidly being transformed through the availability of Southern consumer goods and the penetration of mass communications. Annie observed the circumstances of her modern life and surroundings objectively, without nostalgia and with no false romanticism. “I didn’t see any igloos in my life,” she said in a 2006 documentary. “Only Ski-Doo, Honda, the house, things inside the house.” She documented these things in her drawings just as honestly as her predecessors had documented their own lived experiences in earlier and far different times. Composition (Family Cooking in Kitchen), 2002, exemplifies her interest in “things inside the house.”

Many Kinngait artists had already pushed at the boundaries of expectations regarding what should or could be consumed by the Southern art market, which was still accustomed to picturesque “ethnic” pieces supposedly emerging from a world of shamans and myths. Annie’s mother, Napachie, is one such artist. Her later works, such as Untitled (Alcohol), 1993–94, or Trading Women for Supplies, 1997–98, included dark personal recollections and troubling scenes from her community. Yet at the time Annie’s drawings were first shown in the South, Inuit art was still being compartmentalized by historians of Canadian art. The prevailing expectation was that what is Inuit is not contemporary.

It is worth considering the meaning of “contemporary”—a word that is both a simple description and an elite standard used to exclude certain artists and groups. It has been used for, among other things, art made in the past twenty years, with an awareness of current trends in art history; critical social consciousness in art; and experimentation for its own sake as a value in the arts. Informed by Eurocentric values, this definition often excludes culturally marginalized and remote populations. “Contemporary” can also describe subject matter: the furnishings of a modern house interior; the daily activities of the people represented in a narrative image and the ordinary ways they stand, move, or sit; in short, the contemporary scene.

An honest look at daily life in the Arctic in the twenty-first century through the eyes of a self-aware and often irreverent artist like Annie was a shock for audiences in the South. A select group of dealers and curators were willing to accept that what they were seeing in Annie’s works was important and maybe even unprecedented. Annie came to the attention of the public quietly in a 2001 group exhibition titled The Unexpected at Feheley Fine Arts, a small commercial gallery in Toronto. For most artists, the road to reach a broader public takes years to travel. But through the determination and support of these dealers and curators, Annie’s drawings quickly became celebrated for capturing the spirit of a time when Canada was looking at Indigenous cultures in new ways, not only in the arts, but also culturally, politically, and ethically.

Acceptance in Canada and Abroad

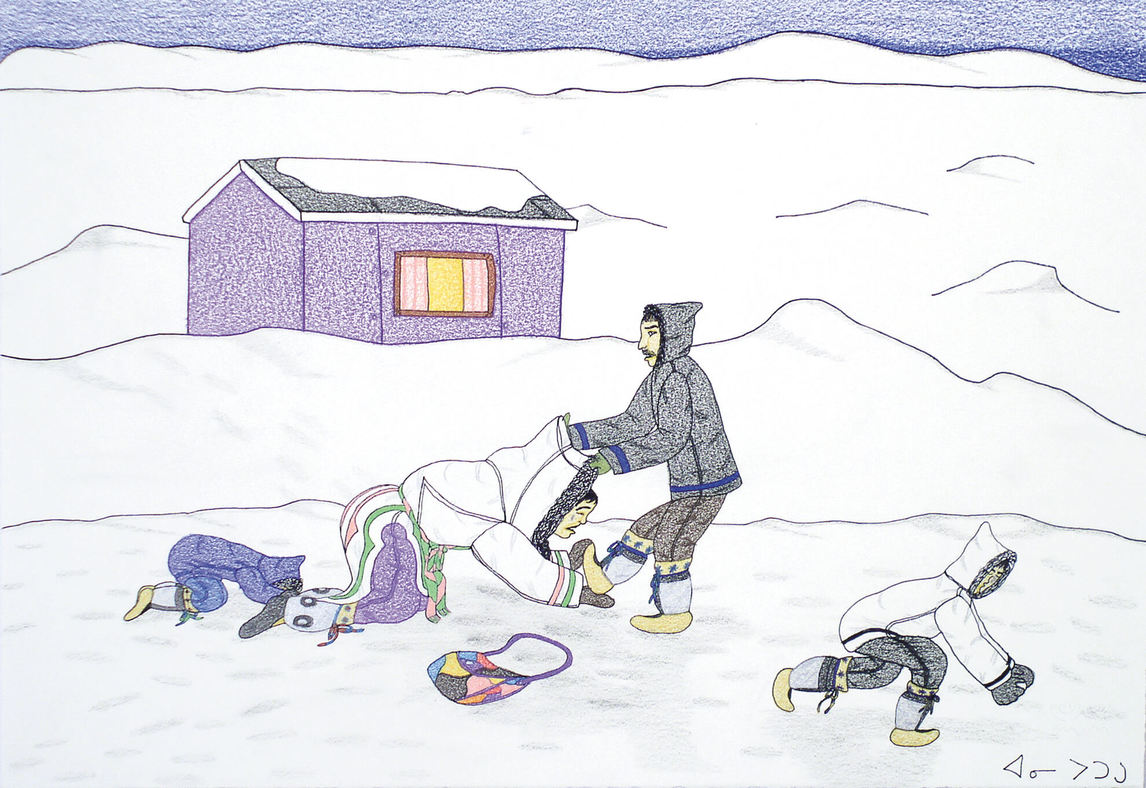

A major shift in Canadian art history occurred in 2006. Annie’s drawings began to be included in numerous exhibitions, including her solo show at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto, a contemporary gallery known around the world for exhibiting cutting-edge Canadian and international art. This exhibition, which included works such as Holding Boots, 2004, and Family Taking Supplies Home, 2006, proclaimed that Annie’s drawings belonged alongside the works of other leading contemporary artists.

Sarah Milroy of the Globe and Mail reviewed the show enthusiastically:

What stops you and makes you look… is the honesty of her reporting. Given the extremity of her personal history—alcoholic parents, domestic abuse, poverty—Pootoogook could be forgiven for seeing what she wants to see, and profiting by peddling to the white world’s expectations: quaint scenes of traditional Inuit life, the redeeming beauty of the natural world and the animals that inhabit it, the fantasy world of myth.

Instead, Milroy continues, Annie shows “beating, drug addiction, despair, all presented with a remarkable lack of histrionics or self-pity.” Nonetheless, in the end Milroy finds that “the tone of the show is one of jubilation.”

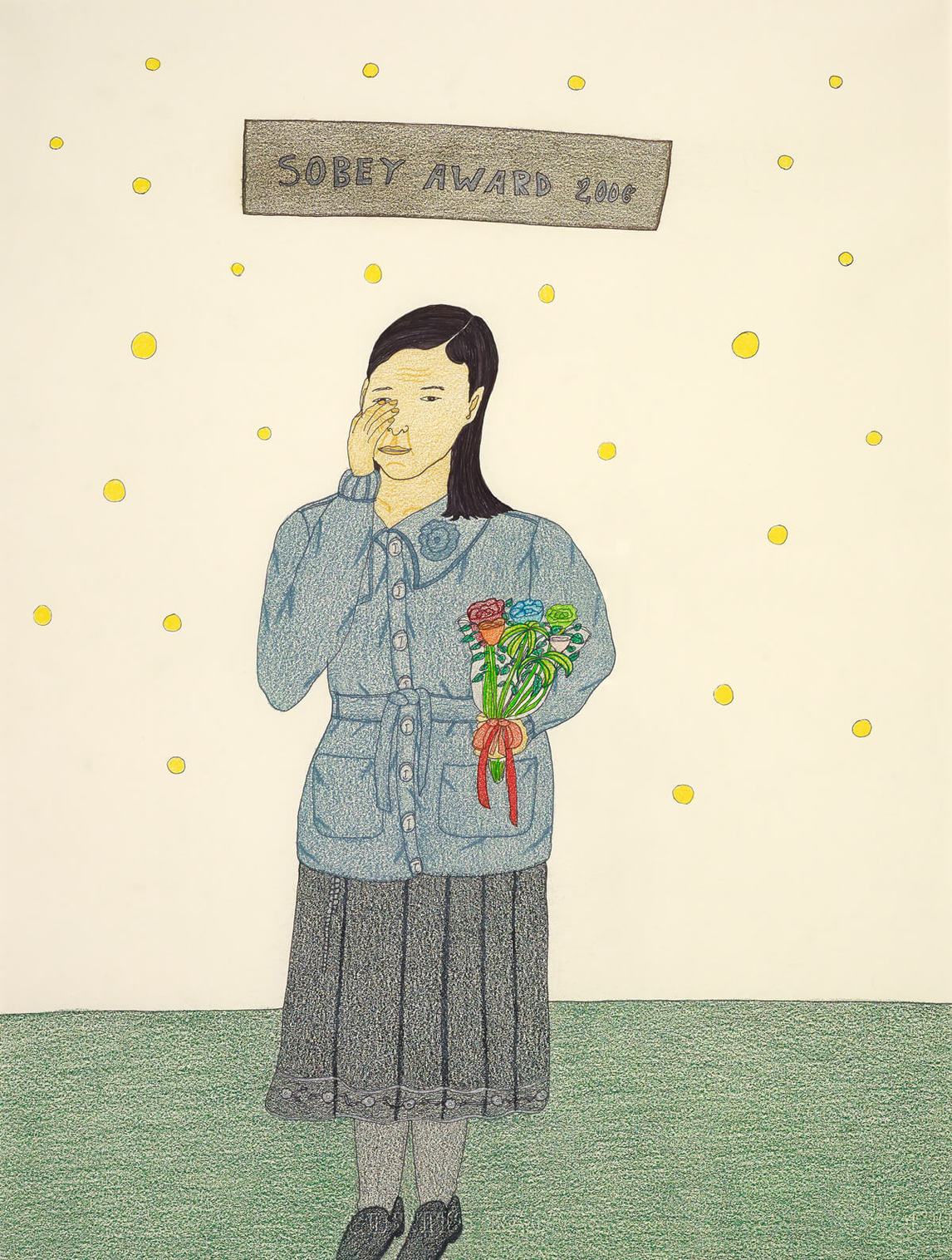

In 2006 Annie’s selection for the Glenfiddich Artists in Residence program in Dufftown, Scotland, was a personal distinction and an opportunity for her to try her hand at unfamiliar landscapes, colours, and light effects. But it was her nomination for the Sobey Art Award, also in 2006, that truly transformed her career. The Sobey Art Foundation formally recognized for the first time that Annie and her generation of Inuit artists were creating relevant works of contemporary art. The foundation, which selects as its nominees contemporary artists from geographic regions across Canada, lacked a classification for artists from Nunavut and the North. Quickly, the curatorial team created a new regional category, “Prairies & the North,” to allow for Annie’s inclusion as a nominee.

No one on the awards committee had imagined that a submission from Nunavut would be considered for this prestigious prize in Canadian contemporary art. The simple fact of Annie’s inclusion in the list of nominees broke through the barriers that had long kept works created by Inuit artists outside the contemporary gallery. However, the choice of Annie as the prizewinner at the award exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in November 2006 was not without controversy, a controversy that revealed discriminatory bias.

Wayne Baerwaldt, former director and curator of the Illingworth Kerr Gallery at the Alberta College of Art and Design (now Alberta University of the Arts) in Calgary and a member of the award jury, explains:

There were so many people on the jury at that time who were resistant to Annie winning…. They said because she was from the North that she wasn’t “informed” enough, hadn’t been exposed to modernism and hadn’t had formal training at art college like other artists did. For me, that was like listening to some 19th century discourse…. I think there was also this long-standing perception that, because of its history, that “Inuit art” is a commercial form of cultural production and therefore “artificial” while contemporary art from the south comes purely from the spirit of the artist and is therefore “authentic.” But who can say what motivates any individual artist, no matter where they come from?

Annie simply expressed her delight that her drawings were “liked.” Her modest words understate by a long shot the monumental shift in art history that took place when the Sobey Art Award panel first considered an Inuit artist for the award and then chose her to be the prizewinner.

The drawings selected for inclusion at the Montreal exhibition, many of them taken from The Power Plant solo show, highlight Annie’s interpretations of contemporary life in the North and a version of her own life in Kinngait. Among them were interiors, exterior community scenes, and portrayals of emotion. Alongside these she presented works such as Man Pulling Woman, 2003–4, that spoke out loudly in a woman’s voice at a time when feminist perspectives were transforming the artistic mainstream.

In 2007 Annie’s works were shown in documenta 12, in Kassel, Germany. The organizers of this prestigious exhibition wrote that they were seeking traces of the postmodern in artwork that crosses “temporal and cultural boundaries.” Annie’s drawings easily fit the criteria; Dr. Phil, 2006, and Ritz Crackers, 2004, were among the works shown. Personally, Annie felt out of place in the high-powered world of global contemporary art. Did she also sense that documenta 12 may have valued her work (consciously or not) on account of its perceived exoticism? A similar question arises when we look at the ways in which Annie was marginalized both as a person and as an artist in Montreal and Ottawa, when she lived in those cities.

Marginalization in the South

Annie chose to stay in the South after her Sobey Art Award win in 2006. She enjoyed the freedom she found in Montreal and aspired to make art outside the system she had grown up in at Kinngait Studios. Yet, like many aspiring artists, she lacked the skills to negotiate the commercial art market on her own and soon found herself in difficult circumstances. She still created drawings, although her production became less regular in the years leading to her death in 2016. The reasons for her decrease in production are complex; they include a lack of guidance and structure, as well as mental health issues, particularly addictions. Equally important, perhaps, was a wider struggle that was being waged, one beyond Annie’s control: how her artwork was to be understood in its new Southern milieu. Annie’s move from North to South exposed a critical flaw in how she was perceived in the context of Canadian art. Seen as an interpreter of the North, she was not accepted in the same way for the work she created in the South.

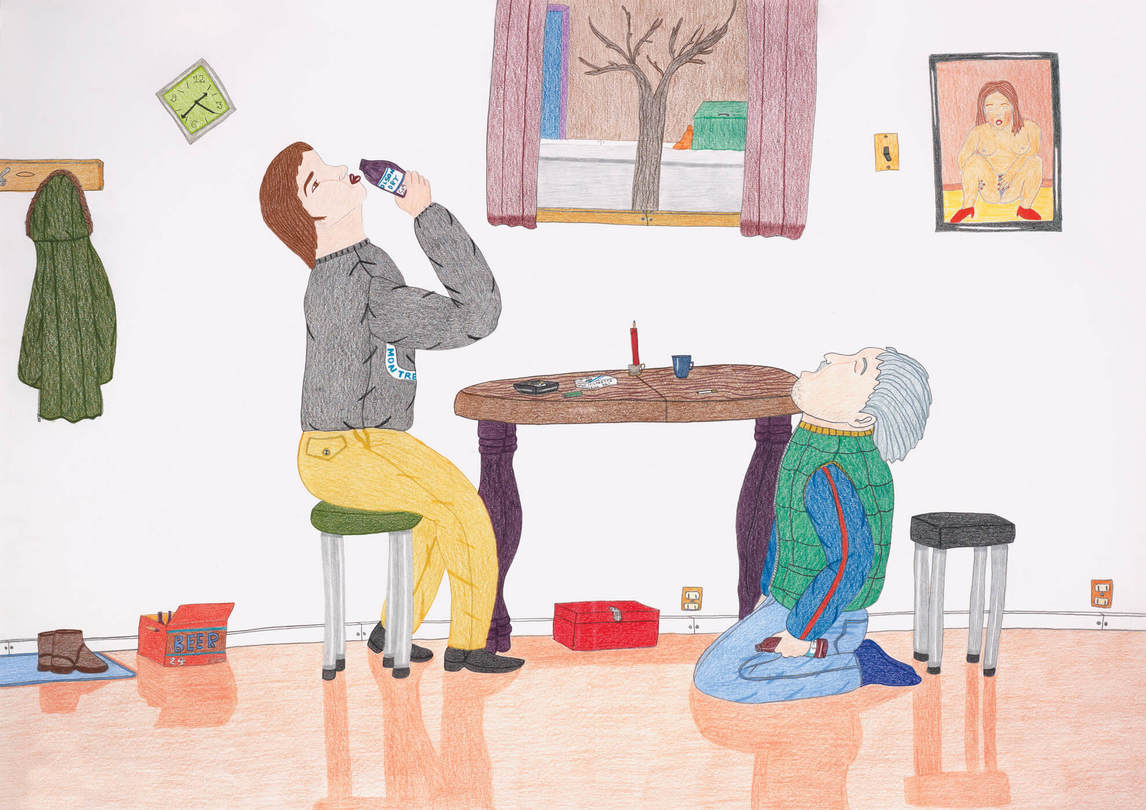

This marginalization becomes evident through an analysis of a significant drawing entitled Drinking Beer in Montreal, 2006. The work sits stylistically and compositionally alongside Annie’s drawings of daily life in the North, but it does not feature any of the notable references to the North that collectors of so-called “exotic” works look for. (Even drawings without polar bears and snowmobiles can have a Northern “aura” if a room is decorated in a certain way, for instance.) In this Montreal setting, where two nondescript men are drinking beer in a room, the window behind them shows not a snowy landscape but a tree, a street, and a recycling bin. Annie’s advanced technical skill is evident. The work is a fine example of the narrative realism that Annie had practised for years in the North—but for most collectors and curators it lacked the seduction of her earlier work. What accounts for this indifference? The truth of the matter is that Montreal was not remote enough or “mysterious” enough for the bias of the Canadian art world.

Drinking Beer in Montreal is as real as Annie’s Kinngait drawings. That it was not embraced in the same way exposes a neo-colonial appetite for Inuit art, an appetite whose preconceptions of what these works ought to be remains unchanged. The things that made her drawings so compelling are still present in works she completed in the South; the drawings were simply rejected by many collectors for not being “Inuit enough,” a disturbing reality that raises important questions about how the art of the North is framed by the tastes and biases of others.

A critical consideration of Annie’s drawings reminds us that it is essential to address the reality of collecting art from the North. There is a colonial impulse attached to the desire to view Inuit art creation as necessarily a collective activity undertaken in a far-off place. This projection of Western definitions of the self, the other, and society stands in the way of a proper understanding of the individual Inuit artist and of the artwork when it is left to stand on its own. Annie’s drawings are the creations of an individual who was part of the human conversation, part of the story of being in the world.

By 2012, six years after leaving Kinngait, Annie was destitute and living on the streets in Ottawa, struggling with addiction and abuse. That a world-famous artist was living outdoors in the city was no secret: that summer, Hugh Adami of the Ottawa Citizen and James Adams of the Globe and Mail wrote about this tragedy. How could an artist who had so many gifts, who was granted opportunities and support, end up living on the streets of Canada’s capital city, camped out near the prime minister’s residence? If there is an answer to be found, some day we may find it along the long road that Canada still has to travel as part of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

Legacy and Impact

Inuit art was nearly absent from contemporary art discourse before Annie’s extraordinary year of 2006. Since Annie’s arrival on the scene, works created by Inuit artists are no longer expected by all who see them to tell the story of an imaginary Canadian identity and a yearning for an exotic, pristine North. They are now widely accepted as expressions of contemporary identities and realities in a physical and social landscape undergoing constant change—whether in the North or anywhere else.

Relegating Inuit art to another space is limiting for the artists producing today and locks them into a colonial system that says who and what is contemporary. Only within the last twenty years has this system slowly begun to break down. Curators, scholars, and art buyers have begun to challenge the traditional segregation of Inuit artists in museums and history books by rethinking the function of art and how their own expectations contribute to the problem. As frank responses to the realities of life in Arctic communities today, Annie’s drawings contributed to this change.

While Annie was shattering the limiting expectations that had been placed upon earlier generations of Inuit artists, she was also honouring their work. Creators such as Pitseolak Ashoona (c.1904–1983), Pudlo Pudlat (1916–1992), Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013), and Oviloo Tunnillie (1949–2014) had announced the existence of a new Inuit art to the world—although audiences still viewed their creations as local and ethnic products. Annie’s Composition: Women Gathering Whale Meat, 2003–4, and other early works interpret traditional Inuit activities meticulously and respectfully, yet with her straightforward and unromantic realism she succeeded in bridging the one-time solitudes of Inuit art and what is understood as contemporary art.

Drawings like Family Taking Supplies Home, 2006, and Cape Dorset Freezer, 2005, present the consumption of Southern imports with cool irony. Annie knew exactly what she was doing here: her Coleman Stove with Robin Hood Flour and Tenderflake, 2003–4, recalls, with a difference, the composition and content of Pitseolak’s Untitled, c.1966–76, with its traditional women’s items on a plain ground. In these works, Annie comments pointedly on the complicated effects of a century of colonial influence in the Arctic, responding both from a socially conscious perspective and from the perspective of an artist working within a respected tradition.

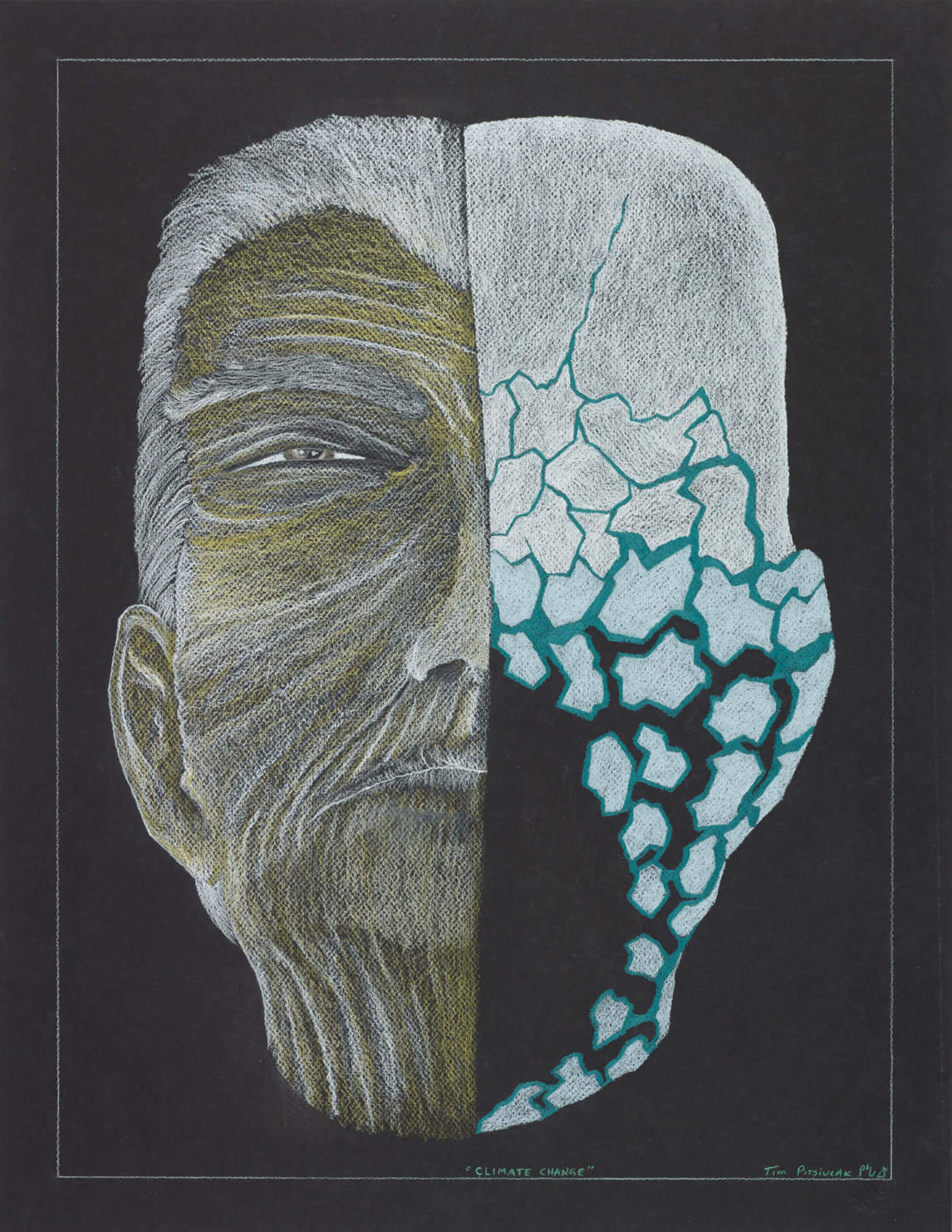

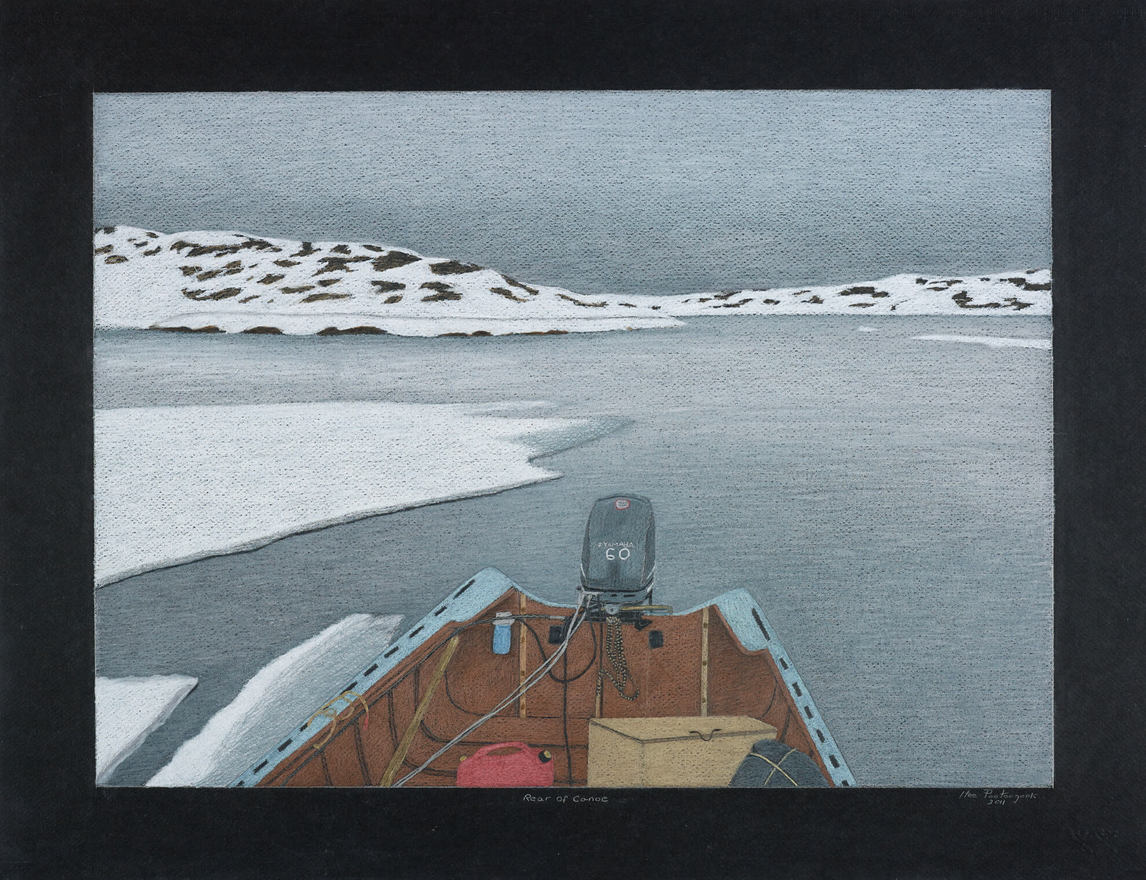

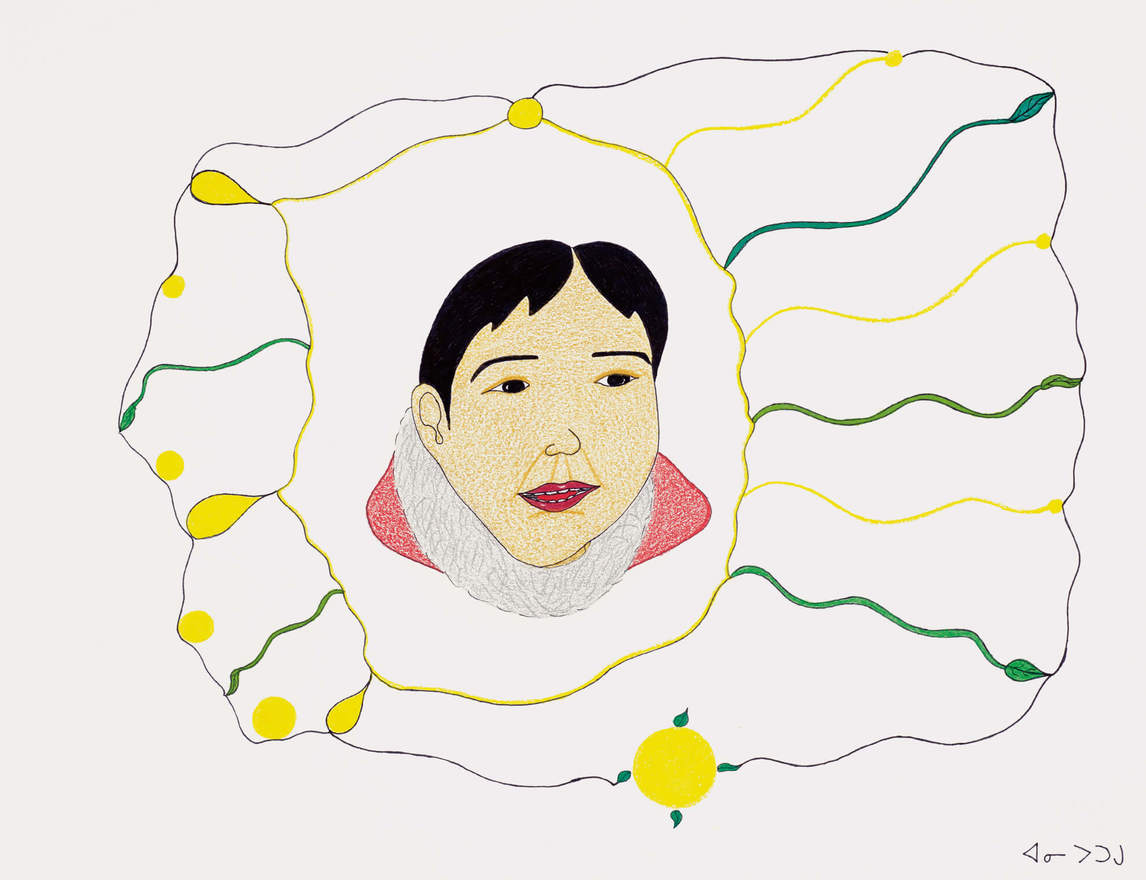

Heather Igloliorte wrote a tribute to Annie in Canadian Art in response to her untimely and tragic death in September 2016. At the time Igloliorte commented that Annie permanently transformed the landscape of Inuit art by “breaking through the ‘ethnic art’ glass ceiling and firmly establishing contemporary Inuit art in the mainstream…. With her smart, unpretentious drawings,” Igloliorte wrote, “[Annie] captured the attention of the international art world and held it for several years, keeping the door open for other Inuit artists to also enter in the process.” These artists include peers from her own generation in Kinngait, notably Shuvinai Ashoona (b.1961), Jutai Toonoo (1959–2015), Siassie Kenneally (1969–2018), Itee Pootoogook (1951–2014), and later Tim Pitsiulak (1967–2016).

The interest in Annie’s drawings marked a change at Kinngait Studios and drawings began to be sold in much greater quantities alongside the long-established Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection. Her drawing Cape Dorset Freezer, 2005, also marked a move to larger papers for some Northern artists (this size works well in museum exhibitions). Today Annie’s name remains known and respected in Kinngait, where young students are introduced to her work. In Ottawa Annie’s friends at Galerie SAW Gallery have named a new studio after her to be used by emerging Inuit artists and as an educational space.

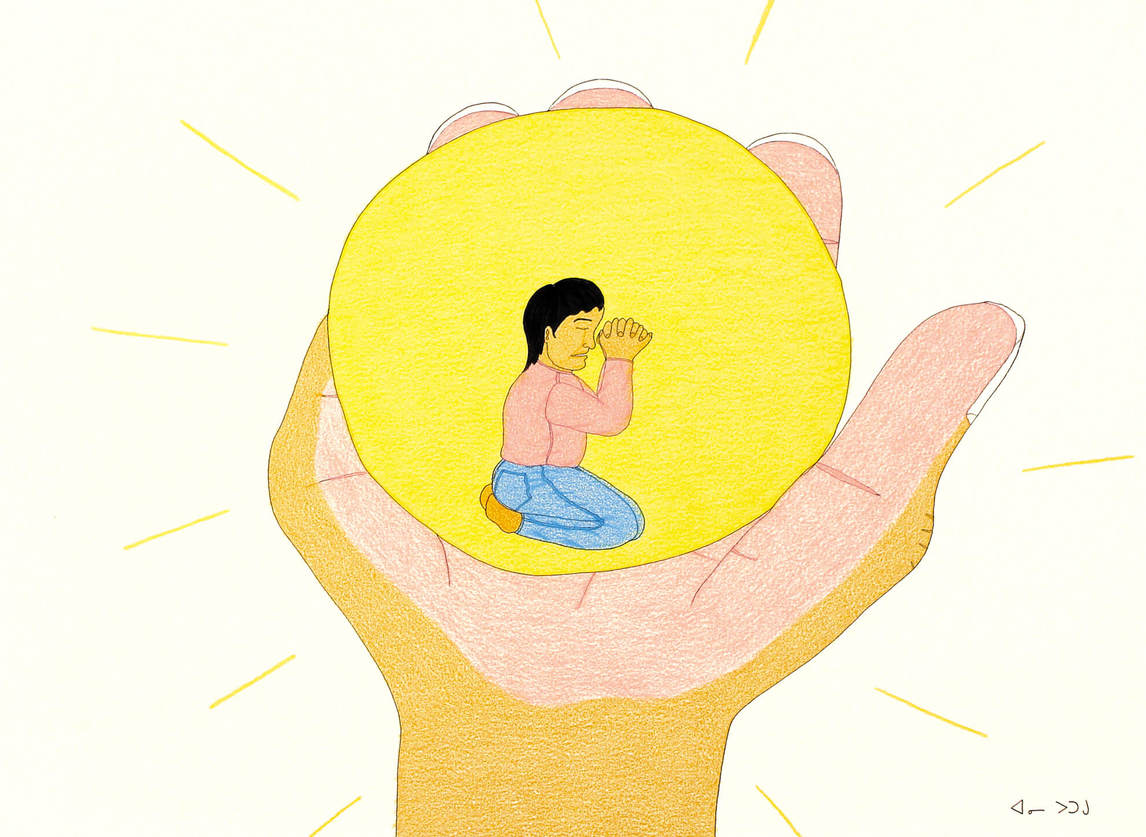

Annie remains well known for her renderings of the darker side of life. Some of her works, such as Man Abusing His Partner, 2002, Memory of My Life: Breaking Bottles, 2001–2, and Hanging, 2003–4, reveal themes of violence and broken social safety nets in Arctic communities. Yet a different picture unfolds from a review of the hundreds of drawings that Annie produced. Many represent a life of love, tradition, joy, and attachment to the land. Jimmy Manning reminds us that when looking at Annie’s drawings, it is important to remember that she was loved in her home of Kinngait and that life in the North has much that is wonderful.

In Canada we are experiencing a renaissance of Inuit art. More Inuit artists are being reviewed, supported, and exhibited in exhibitions of contemporary art than ever before. Museums are focusing on the gaps in their collections and acquiring significant works of Indigenous art, an area that now includes works done by Inuit artists. Progressive collectors and curators no longer dismiss Inuit artists’ creations as handicraft or tourist art. Annie’s striking, powerful drawings were central to this movement. She captured the attention of the broader contemporary art world at a critical point in Canada’s ongoing reconciliation process.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements