Alex Colville’s drive to make sense out of life—which marked his work from his return from the army in 1946 until his death in 2013—is at the heart of his significance as an artist. He was intent on creating a world of order from the reality of chaos, always aware of the essential and tragic fragility of this Sisyphean task. Colville was a thinker as much as a maker, and his sustained, rigorous approach to creating images is a remarkable legacy. At his death he was the best-known artist in Canada, and his body of work includes some of the most iconic images ever created in this country.

Influence of the War

Like so many men and women of his generation, Alex Colville felt a call to serve during the Second World War. He enlisted, hoping to be an official war artist, and after two years of training and general duties was so appointed. The Third Canadian Infantry Division was a veteran unit by the time the newly minted Second Lieutenant Alex Colville joined it. The division landed at Juno Beach on D-Day and fought its way down Normandy through Caen and Falaise. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery christened the unit the “Water Rats” during the Battle of the Scheldt in Belgium and the Netherlands, a nod to the Canadians’ bravery and perseverance in terrible conditions and a reference to Montgomery’s own “Desert Rats” who had driven the Germans out of North Africa. Colville’s most successful painting of this time is Infantry, Near Nijmegen, Holland, 1946, a moving portrait of a line of infantrymen slogging through a flooded field—an image that well underlines Montgomery’s point.

While assigned to the Third Canadian Infantry Colville was exposed to the full horrors of war; not actual combat, though he was often close to action, but the horrific aftermath of full-scale mechanized war. Shattered villages, splintered forests, churned ground, and dead soldiers, civilians, and farm animals littered the landscape such that the sight of bodies became so common it must have seemed routine. Colville described his practice as a war artist as subjective. “You are not a camera,” he said. “There is a certain subjectivity, an interpretive function.” In A German Flare Goes Up, 1944, Colville, close to action, records a river crossing by Canadian troops. Being exposed is also being at risk, and Colville depicts the tension of the moment through the rigidity of the soldier in the foreground and the overall emotional tenor of the work.

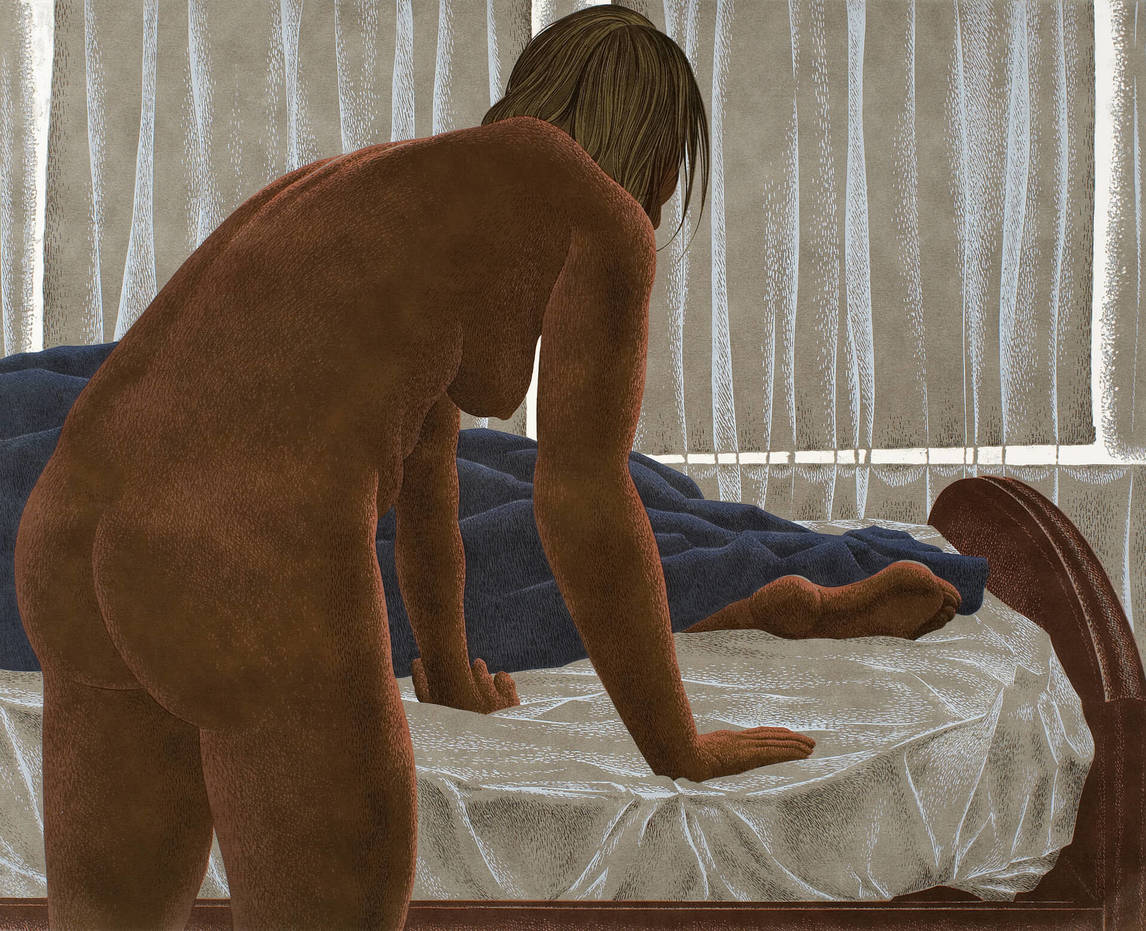

Colville’s most important assignment during his time as a war artist was at the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. Here, more than any other time in the twenty-five-year-old Colville’s experience of war, he witnessed the full potential of human depravity, and the encounter was traumatic and lasting. He later said of it, “One felt badly because one didn’t feel worse. That is, you see one dead person and it is bad: five hundred is not five hundred times worse. There is a point at which you begin to feel nothing. There must have been 35,000 bodies in that place and there were people dying all the time.” German philosopher Theodor Adorno famously wrote, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” How does one continue to create poetry, or any art, after the despair and horror of what humans have done to one another? Is there any room for hope? For Colville, and many of his peers, the answer was a qualified “Yes.” His experience of the war and its numbing effect profoundly impacted Colville’s work, preparing him for the existentialist philosophy and the new approach to painting that he would explore in the 1950s. His sustained search for order was his way of coping with chaos, evident in such works as Nude and Dummy, 1950, Four Figures on Wharf, 1952, and Woman, Man, and Boat, 1952.

Thinking as Painting

Alex Colville’s work represents one of the most coherent bodies of painting in Canadian art history, a sustained look at basic philosophic issues that remained central to his practice from 1950 until his final painting in 2010.

In the early 1950s Colville turned to existential philosophy, and was much influenced by Albert Camus (1913–1960), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980), and Martin Heidegger (1889–1976). All three questioned the state of human beings in the world, a world whose certainties had been undermined, seemingly forever, by the trauma of the two world wars. Their insistence that humans be viewed as free and responsible agents who express their freedom through acts of will was an immensely attractive assertion to a generation haunted by war. As Tom Smart wrote, “In artistic terms, existentialism sees art as an attempt to give the world the coherence, order and unity it lacks, and Colville was drawn to this structure.”

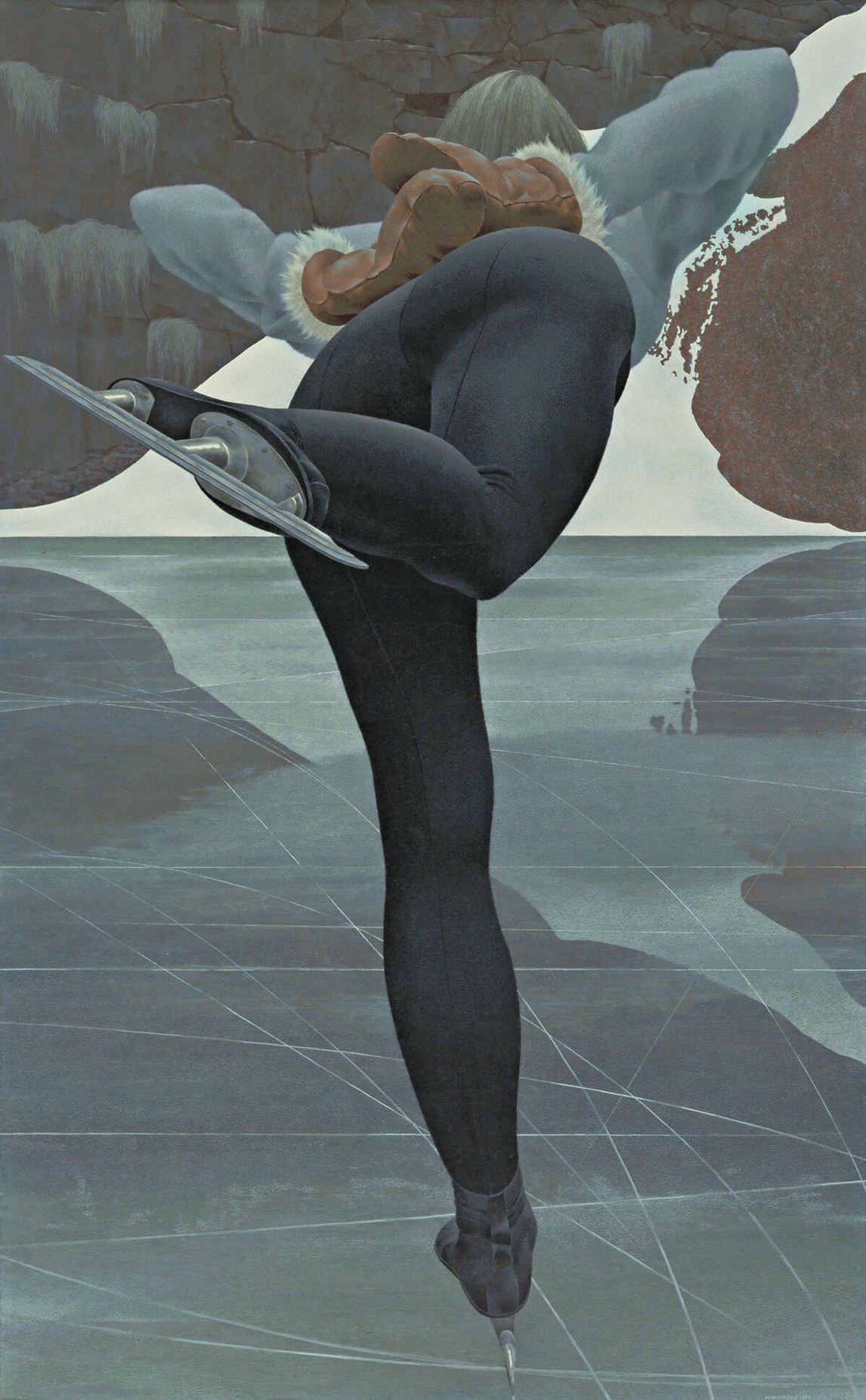

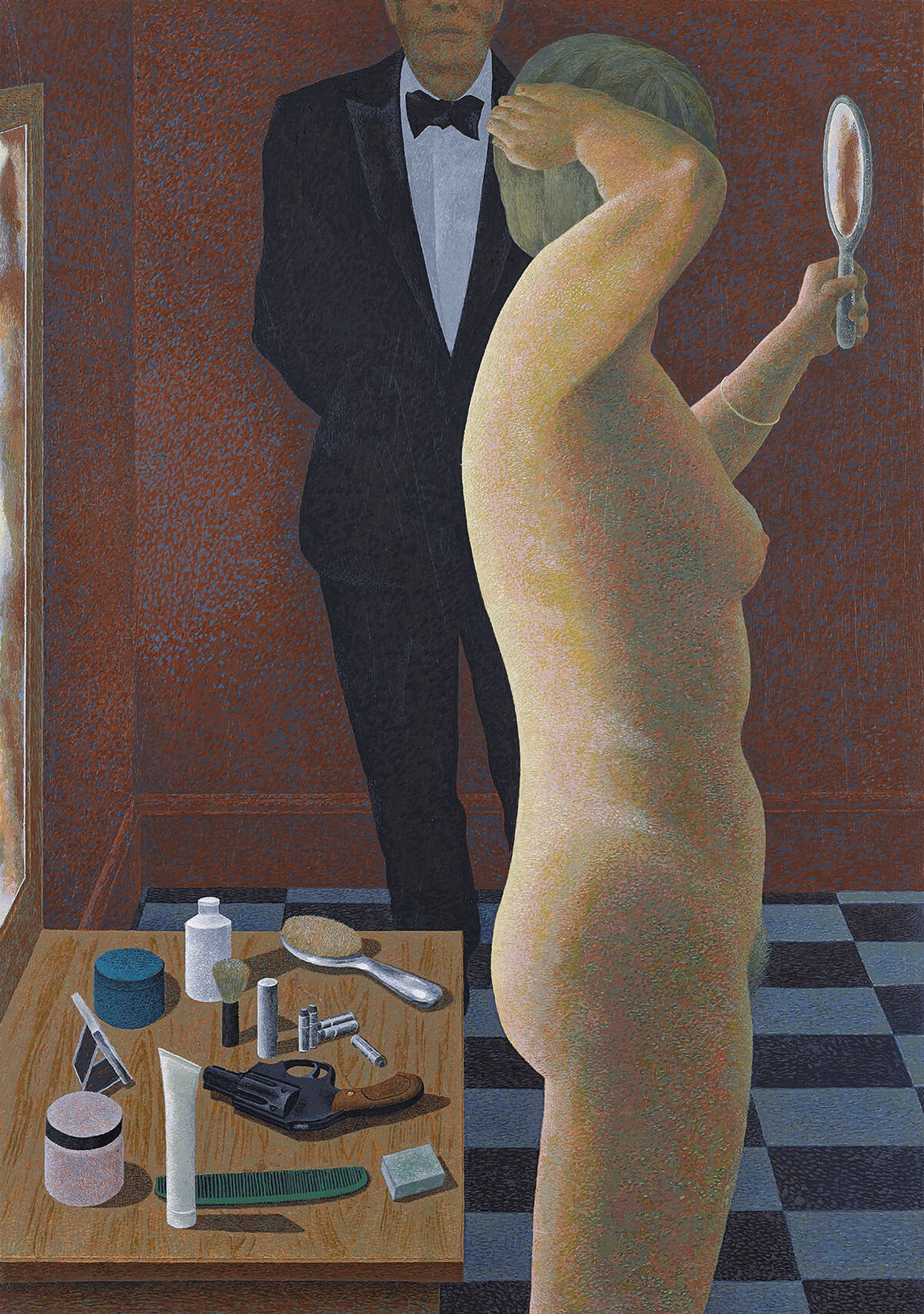

Colville, in his insistence on order, on making sense, echoes Camus’s definition of a “metaphysical rebel” as one who “attacks a shattered world in order to demand unity from it.” Colville is a man in revolt against a world that promises only tragedy. “Rebellion is born of the spectacle of irrationality, confronted with an unjust and incomprehensible condition,” Camus states. “But its blind impulse is to demand order in the midst of chaos and unity in the very heart of the ephemeral.” This demand is a key theme in Colville’s work, most evident in such images as Horse and Train, 1954, Skater, 1964, or Target Pistol and Man, 1980. In each of these, and so many other works by Colville, the artist presents a situation in which order and chaos are equal possibilities: the horse and train may collide with catastrophic effect; the skater may lose her precarious balance and tumble to the ice; the man may pick up the pistol and use it. Colville posits moments of stasis in order to anchor us in a chaotic world. His rebellion lies in refusing to accept the eventual triumph of entropy and in seeking stability and endurance despite knowing they are ephemeral.

Colville insisted throughout his career on order; he, too, opposed a brain against a regiment and “a dark horse against an armoured train.” His insistence on the rational underpinning of all his compositions, his focus on his immediate surroundings, was perhaps an attempt to use thought against the ever-encroaching nothingness of the abyss.

At a time when Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism were major influences on Canadian painters, Colville took his own path. Colville’s intellectualism, his assertion that reason trumps passion, and his reliance on tradition in painting distinguished him from the mainstream of critically acclaimed Canadian painters. As journalist Robert Fulford noted in his 1983 profile of Colville, “We can most profitably see Colville within the context of Canada—not the Canadian art scene but the larger field of Canadian culture.” Fulford maintains that Colville should be considered part of the intellectual history of Canada, alongside such thinkers as George Grant (1918–1988) and Northrop Frye (1912–1991), with their own brand of conservative rebellion, more so than with his artistic peers of the period, such as Jack Bush (1909–1977), Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), or Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002).

A Personal Realism

Alex Colville eschewed abstraction at the height of its critical acclaim in North America. In Canada, the art scenes of the 1950s and 1960s were dominated by movements and groups influenced by or responding to Abstract Expressionism, such as the Automatistes, the Regina Five, and Painters Eleven. Colville was simultaneously an outlier and a success. He had his first solo show in New York in 1953, he represented Canada at the Venice Biennale in 1966, and he began exhibiting in Germany and Britain in the late 1960s. He achieved this without being associated with the most influential art movements of the day: abstract art, Pop art, and Conceptual art.

Despite his early self-description as an artist whose work was based in ideas, Colville has mostly been thought of as a realist, his work linked to numerous variations on the genre. In the 1950s he became associated with magic realism because he showed in New York at the Hewitt Gallery, a noted dealer of self-styled American Magic Realists such as George Tooker (1920–2011) and Jared French (1905–1988). Somewhat later in his career, his work became the leading example of “Atlantic Realist” painters, a category with little stylistic meaning beyond the biographic realities of having lived in Atlantic Canada and studied at Mount Allison University. This term applies to some of Colville’s Mount Allison students, most notably Christopher Pratt (b. 1935), Mary Pratt (b. 1935), Tom Forrestall (b. 1936), and their imitators.

Colville has also been grouped with Photorealism, a style popular in the early 1970s and typified by artists such as Robert Bechtle (b. 1932) or Richard Estes (b. 1932), who recreate the visual effects of photography in their paintings. However, this is an awkward association given Colville’s methods of working and his avowed interest in making a world, rather than depicting one in front of him. He often used photography as a tool, but never attempted to recreate photographic effects, unlike the paintings of such artists as Chuck Close (b. 1940) and Mary Pratt. In speaking of his relationship with photography Colville said, “Photographs tend not to give me the information that I want, and do give me the information that I don’t want…I think this has also something to do with memory; it is important for me to be able to forget some things…the camera takes everything, forgets nothing.”

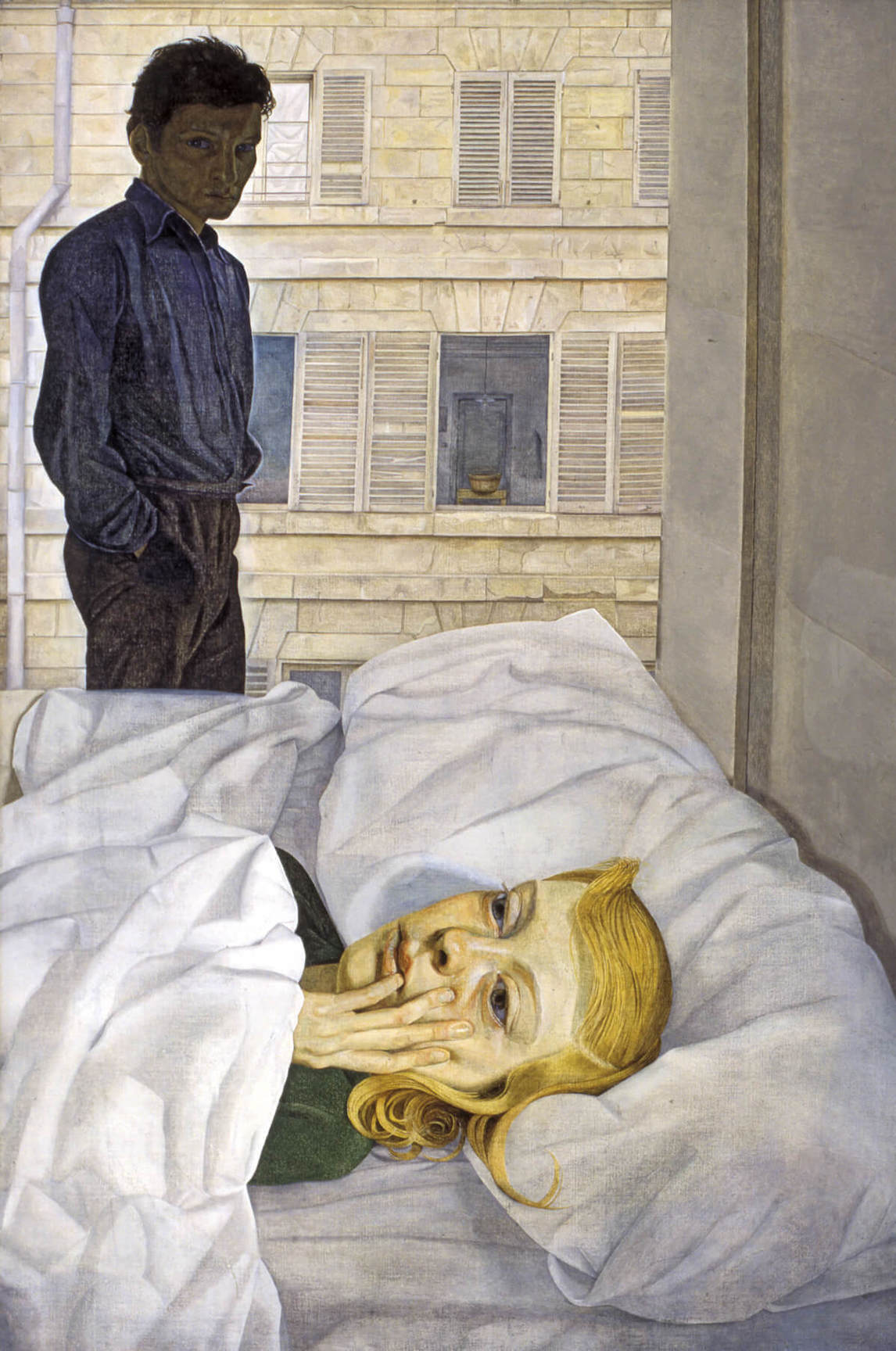

Colville is a representational painter, but his concern with creating images based on ideas about being human, his desire to make sense out of life, allies him as much with idealism as with realism of any stripe, and he doesn’t fit easily into any convenient grouping. It is fair to think of him as a realist painter, but one whose peers are Lucian Freud (1922–2011), Balthus (1908–2001), Edward Hopper (1882–1967), or Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009). Freud’s Hotel Bedroom, 1954, for instance, shares the psychological depth and tension of Colville’s best work. Colville did not want to fool the eye—if anything he was trying to get us to see more deeply than we usually do. His Dressing Room, while thematically similar to the Freud painting at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, differs in some key respects: Colville depicts a woman at ease with herself and her power, one who lacks the sense of despair seen in the Freud. The pistol on her dressing table serves to heighten this sense of power and menace; the male figure in the background is left deliberately mysterious.

Depicting the Everyday

In a sense the things I show are moments in which everything seems perfect and something is revealed.

—Alex Colville

Colville’s abiding interest in the nature of being led him to examine the everyday facts of existence. His subject matter is, almost exclusively, the daily life that surrounded him, whether that was in Sackville, Wolfville, or while he was on a sojourn in Santa Cruz or Berlin. For Colville, thinking deeply happens wherever you are, and happens best with familiar things. As art historian Martin Kemp notes, “He is a local painter in the sense that Constable was local, creating art that has to draw nourishment from scenes known intimately in order to find a wider truth.”

His approach is literary, as has been noted by such writers as Mark Cheetham and Robert Fulford. His interest in the everyday echoes that of a fiction writer such as Alice Munro (b. 1931): Colville constructs extraordinary images out of ordinary experience. He is a storyteller of sorts but without a message to deliver. Cheetham notes, “To suggest that Colville’s images are imbued with narrative elements by viewers is not to claim that he narrates the scenes that he constructs. By the same token, though he is careful to depict only what he understands, not all that he shows is his experience. He creates fictions, just as the novelists that he admires do.” Colville was an inveterate consumer of fiction, particularly drawn to writers who were “realists” and who depicted day-to-day life in difficult times. Among his favourites were Ford Madox Ford (1873–1939), Joseph Conrad (1857–1924), Iris Murdoch (1919–1999), Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961), John Dos Passos (1896–1970), Alice Munro, Thomas Mann (1875–1955), and Albert Camus (1913–1960).

In Colville’s depictions, simple binaries create complex images that resist easy summation. Humans and animals, men and women, humans and machines, the constructed world and the natural environment, are all put into play in his “fictions.” He begins with ideas, and uses familiar objects to express them. According to Colville, “My paintings begin as imaginary drawings, and then at a later point in their development, I make some drawings from life, from reality. It’s interesting that the original conception of one of my paintings, or my prints, always emerges out of my head, rather than from something specifically seen. It’s a sort of conglomeration of experience and observation.”

Animals play a key role in Colville’s work, often standing in as a counter to human figures. The animal is Other, present, seemingly ubiquitous in Colville’s imagery, but essentially unknowable. As his daughter, Ann Kitz, told curator Andrew Hunter, “He wasn’t sentimental about animals, but he thought that they were essentially good, and he didn’t think that people were inherently good.” Colville uses animals as a compositional pairing—such as in Dog and Groom, 1991—that forms an essential binary in his work: human/animal or, perhaps more accurately, culture/nature. For Colville, humans think, animals act, and in their juxtaposition something important about the world can be expressed. As Hunter notes, “Colville’s bond with animals (particularly the family dogs that appear in so many works) was genuine and consistently evident. He seemed to think both about and with them, to work toward understanding the world in tandem with them.”

For Colville, so influenced by existentialism and its restless pursuit for the meaning of human nature, animals provide a foil to further his philosophical engagement. As he stated early in his career: “The great task which North American artists have to perform is one of self-realization, but a self-realization much broader and deeper than the purely personal or subjective. The job thus involves answering such questions as, ‘Who are we? What are we like? What do we do?’” Colville posed these questions through the use of symbols: “I am suggesting that primeval myths may be of use to the modern painter.… What I have in mind is the use of material so old, so often used down through the ages, that it has become an integral part of human consciousness.”

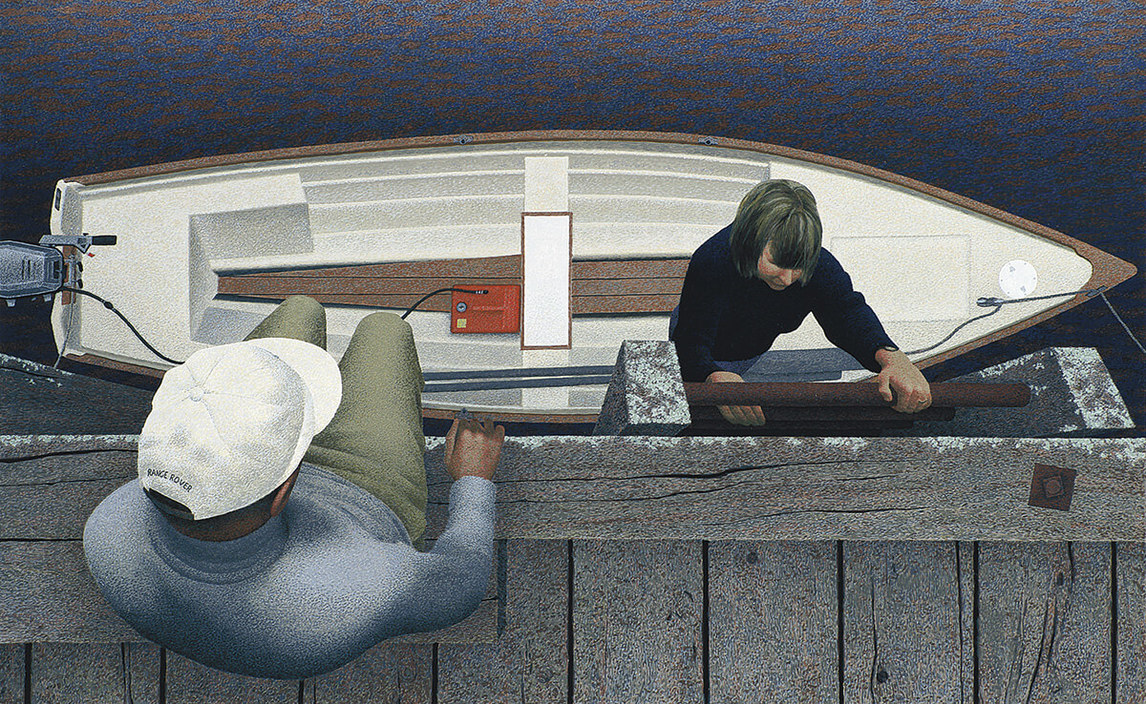

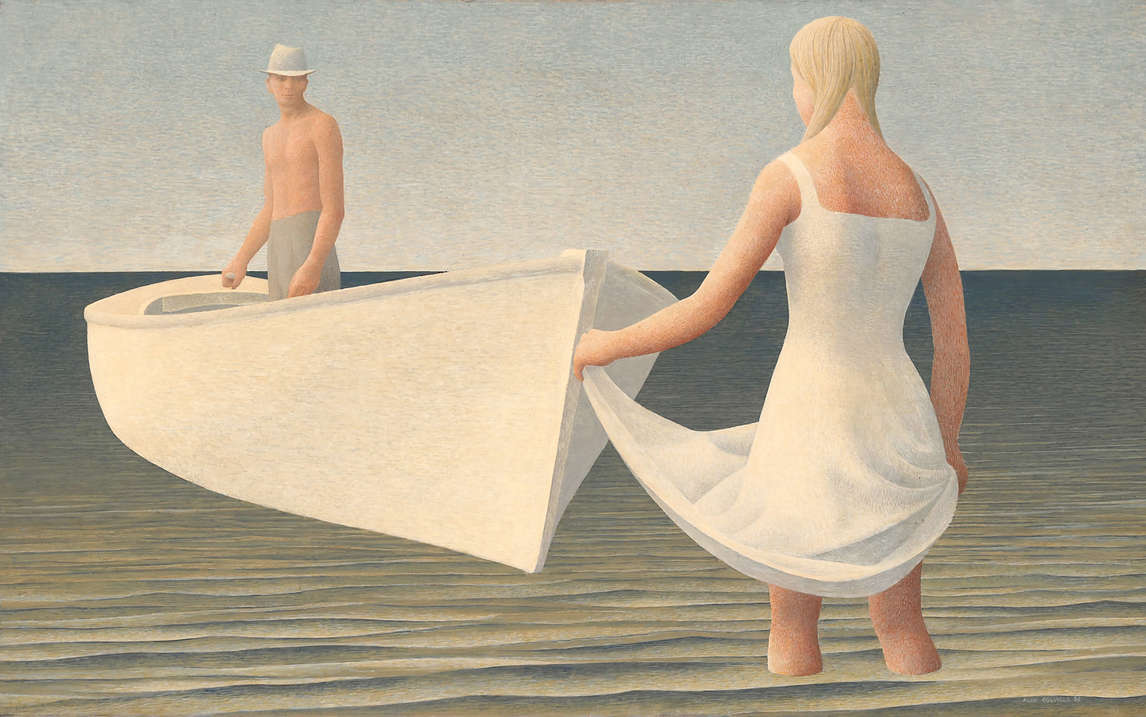

Boats, for instance, can stand in for a journey—the increasing distance between a parent and child as the child grows up, as in Embarkation, 1994, or a lover’s return, as in Woman, Man, and Boat, 1952. Colville’s use of the everyday is extremely purposeful. His paintings are at once familiar, depicting images that reflect common human experience, and mysterious, imbuing quotidian moments with depth and purpose too often lacking in our lives. As he wrote in 1967, “It is hard to improve on the aims of art given by Pope Gregory in the so-called dark ages, ‘to render visible the mysteries of the supra-natural world.’”

A Painter of Influence

Colville’s influence is hard to define. In part, his association with Atlantic Realism has positioned the artist as a leading influence on his former students Christopher Pratt (b. 1935), Mary Pratt (b. 1935), and Tom Forrestall (b. 1936), among others. However, he refused to be categorized with any group or style. As he told The Globe and Mail in 2003, “I’ve never been associated with any kind of artists’ group. In fact I find the idea deeply distasteful.” He has many imitators and self-appointed acolytes, too many of whose works fulfill Colville’s definition of bad art—works that are commercial, sentimental, and retrograde. But it is difficult to point out a lasting influence beyond that of his example; there is no “Colvillism” in serious painting. Yet his approach has had an impact: his portrayal of archetypal scenarios in contemporary guises (as in the representations of leaving and returning mentioned above), his use of tension to undermine order even as he creates it, and his philosophical approach to artmaking has reverberated through Canadian art.

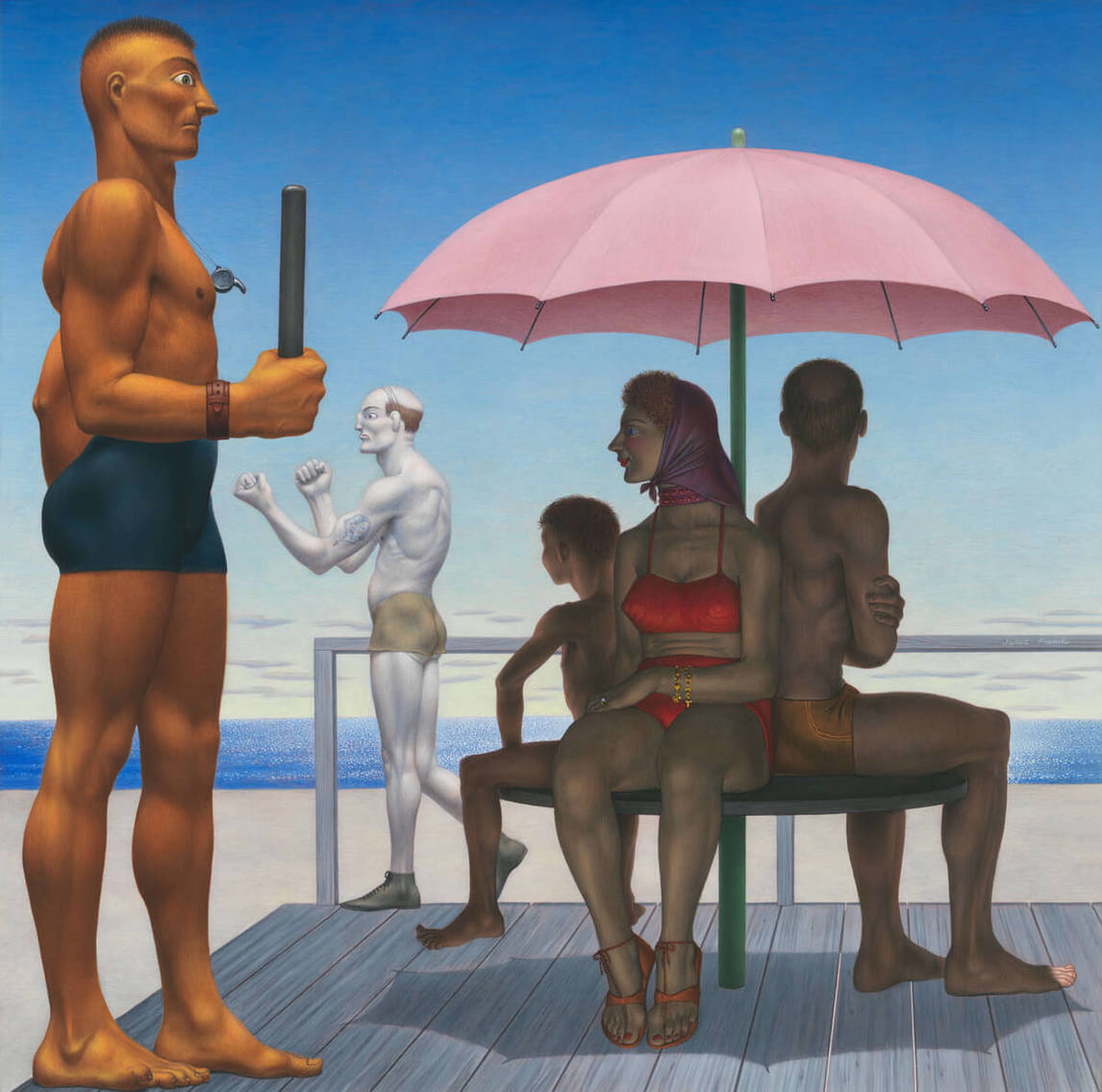

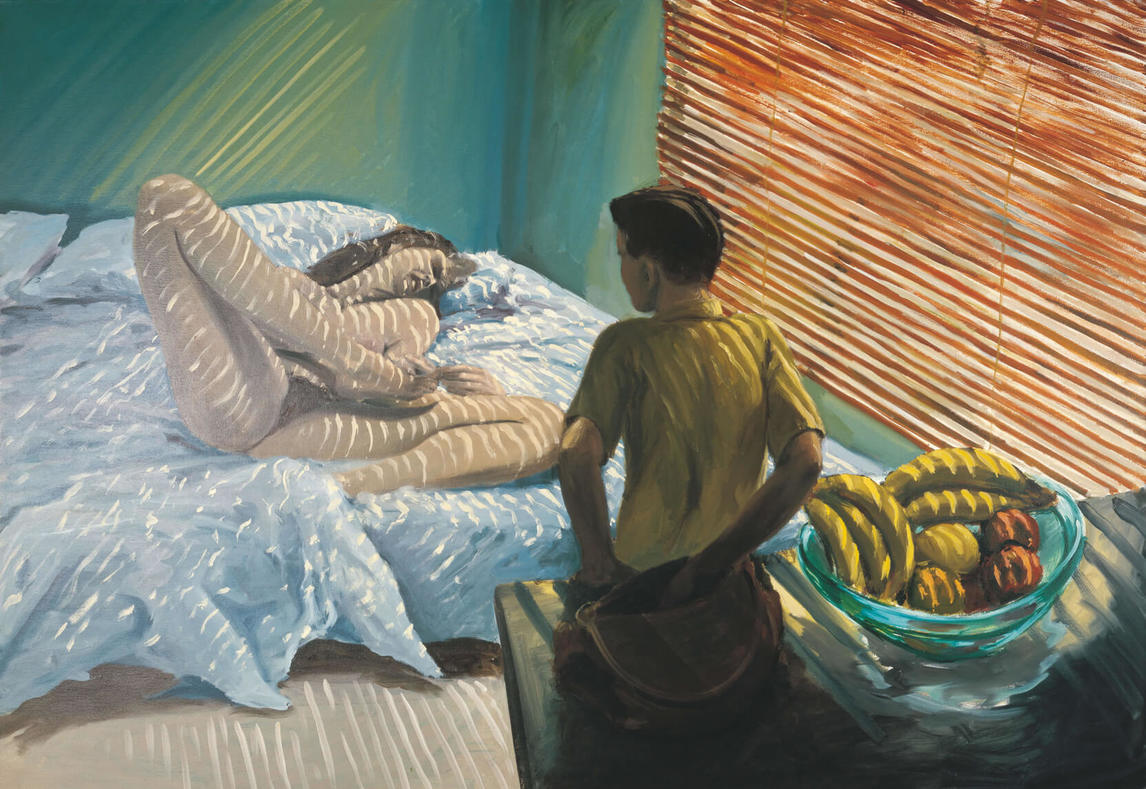

At the end of the 1970s, when Colville was at the height of his career, artists such as Eric Fischl (b. 1948), Tim Zuck (b. 1947), and Jeffrey Spalding (b. 1951) turned to a form of conceptual realism in their painting. They were teaching in Halifax at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (now NSCAD University), and could hardly have evaded an awareness of Colville’s work. Fischl’s Bad Boy, 1981, painted just a few years after he left Nova Scotia, is a realist painting with built-in tension and drama that is closer to Colville’s work (as in Sleeper, 1975) than are the works of most of Colville’s “realist” imitators.

In the 1990s a school of conceptually based sculpture arose, with realism as the starting point. Colville was not an influence per se in the work of artists such as Thierry Delva (b. 1955), Colleen Wolstenholme (b. 1963), or Greg Forrest (b. 1965), but all three studied at NSCAD, live in Nova Scotia, and share with Colville the intent of making an idea concrete through the choice and replication of an image. Colville’s insistence on the importance of objects as symbols, and on the weight of ideas in the depiction of objects as they are in the world, was inherent to these artists’ sense of “sculptural realism.”

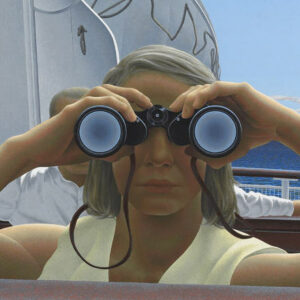

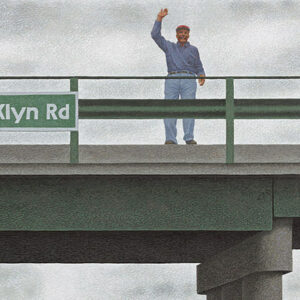

In a way, Colville’s influence has permeated the region he so intently used as his subject matter. As Sarah Fillmore, chief curator of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, said on the event of his death in 2013, “As a sort of mentor and teacher and as an artist who was very present in this region, his loss will be felt. The students that he has had, the kind of visual language that he has helped to create—there’s a strong sense of it.” His impact, and that his work is both good and popular, was evident in the 2014 Colville retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Curated by Andrew Hunter, this exhibition integrated popular-culture works and references, particularly from film, wherein the curator perceived echoes of Colville’s work. For instance, To Prince Edward Island, 1965, was exhibited alongside a film still of young girl looking through binoculars in Moonrise Kingdom, 2012, a film by Wes Anderson (b. 1969); and Man with Target Pistol, 1980, was shown with stills from No Country for Old Men, 2007, by Joel (b. 1954) and Ethan Coen (b. 1957). Stanley Kubrick (1928–1999) consciously referenced Colville in the film The Shining, 1980, which included posters of Colville’s paintings, for example Dog, Boy, and St. John River, 1958, in its set decoration. The retrospective’s highlights of these echoes show how effective Colville’s strategy was—even as he concentrated on creating images drawn from his specific surroundings and experience, he was able to evoke a universal language of myth and metaphor that reverberates throughout our culture.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements