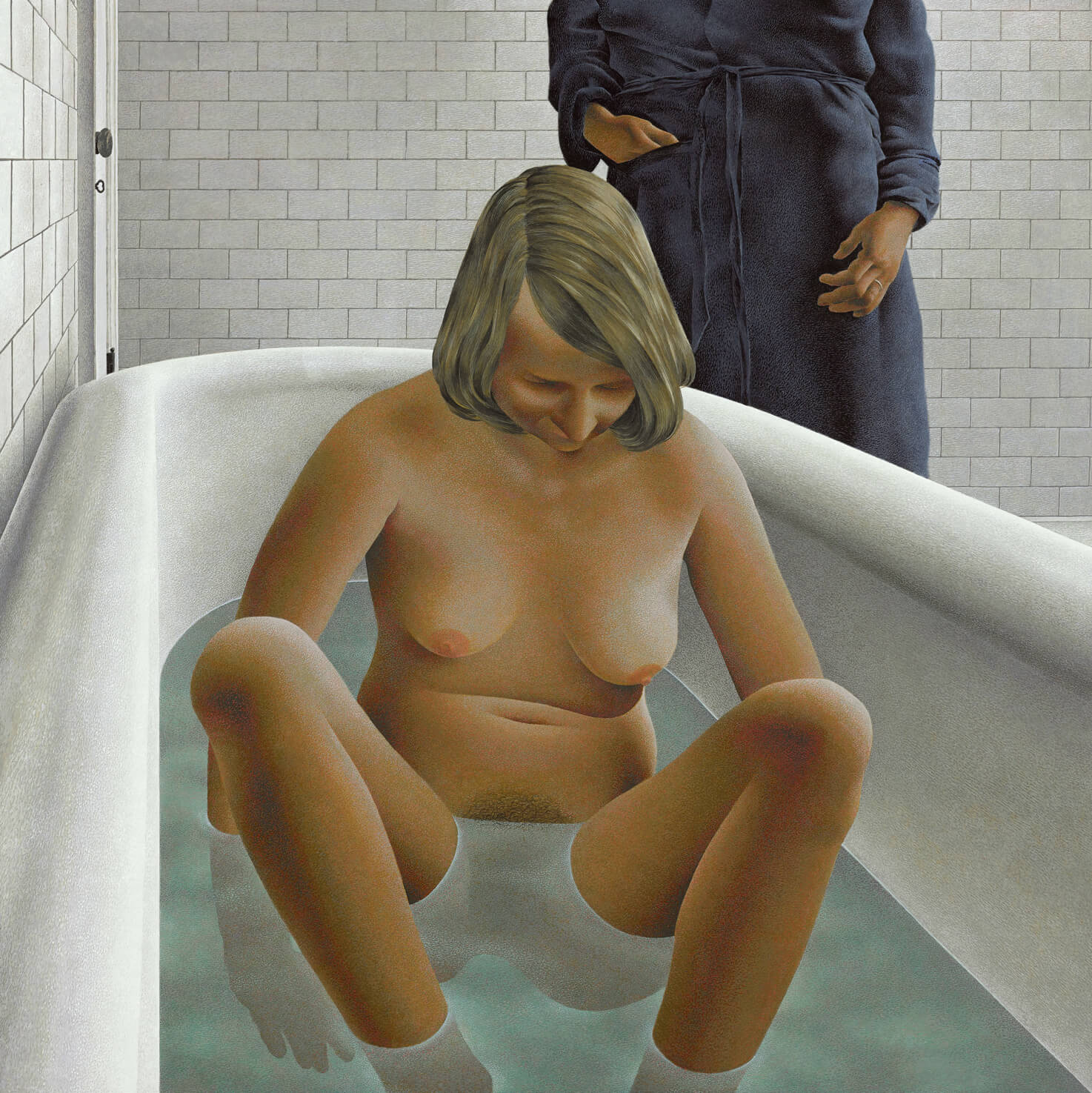

Woman in Bathtub 1973

Alex Colville, Woman in Bathtub, 1973

Acrylic polymer emulsion on particleboard, 87.8 x 87.6 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

This is one of Colville’s most disturbing images. Of the many scenes the artist depicted using himself and his wife, Rhoda, as models, Woman in Bathtub stands out as one that explores the darker and more disquieting side of male/female relationships. Although the woman is in a vulnerable position, and the man is in one of authority, the sense of menace comes from our reading of the painting, not the image itself.

The female figure seems awkward and somehow imbalanced, as if she is about to rise or shift her position. The male figure, conversely, is very at ease, clad in a dressing gown, one hand in his pocket, exuding comfort and a sense of place, of ownership. Though this image depicts the artist and his wife, paintings are not biography, and viewers can only deal with what they see: a nude woman hunched over in the bath; an anonymous man looming over her left shoulder; and a room stripped of any identifying clues and with no domestic clutter, not even a towel—just cool porcelain.

The relationship between men and women is a common theme in Colville’s work. He used images of himself and Rhoda in domestic settings to make powerful, complicated paintings that speak to fundamental truths and mysteries of human connection. How can we know anyone, even the person we have lived with for decades? From his first serigraph, After Swimming, 1955, to one of his last paintings, Living Room, 1999–2000, each depiction of that relationship is a visual manifestation of the notion of “two becoming one.” Additionally, the two figures are often shown at contrasting poles of behaviour: the male as outward-focused, the female closer to nature or the body’s realities.

The juxtaposition of nude female and clothed male figures in painting has a long history, from religious paintings such as depictions of Susanna and the Elders; to artworks based on myths, such as the Judgement of Paris, or legends, such as the Rape of the Sabine Women; through to modern works, such as Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1862–63, by Édouard Manet (1832–1883). Perhaps the most common composition depicts the artist and his model—a reflection on artistic inspiration and on power relationships, with the male creator viewing the object that inspires his creation.

Colville’s layered imagery, with its ability to seem filmic despite being static and singular, is well displayed in this painting. A disconcerting feeling of incipient threat permeates this work, while it remains a simple domestic scene. Colville presents

a moment when the few facts, innocent enough on the surface, can induce an ill-defined sense of fear. This sense of impending doom reflects Colville’s view of human life as fundamentally tragic. As he once said, “I see life as inherently dangerous. I have an essentially dark view of the world and human affairs.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements