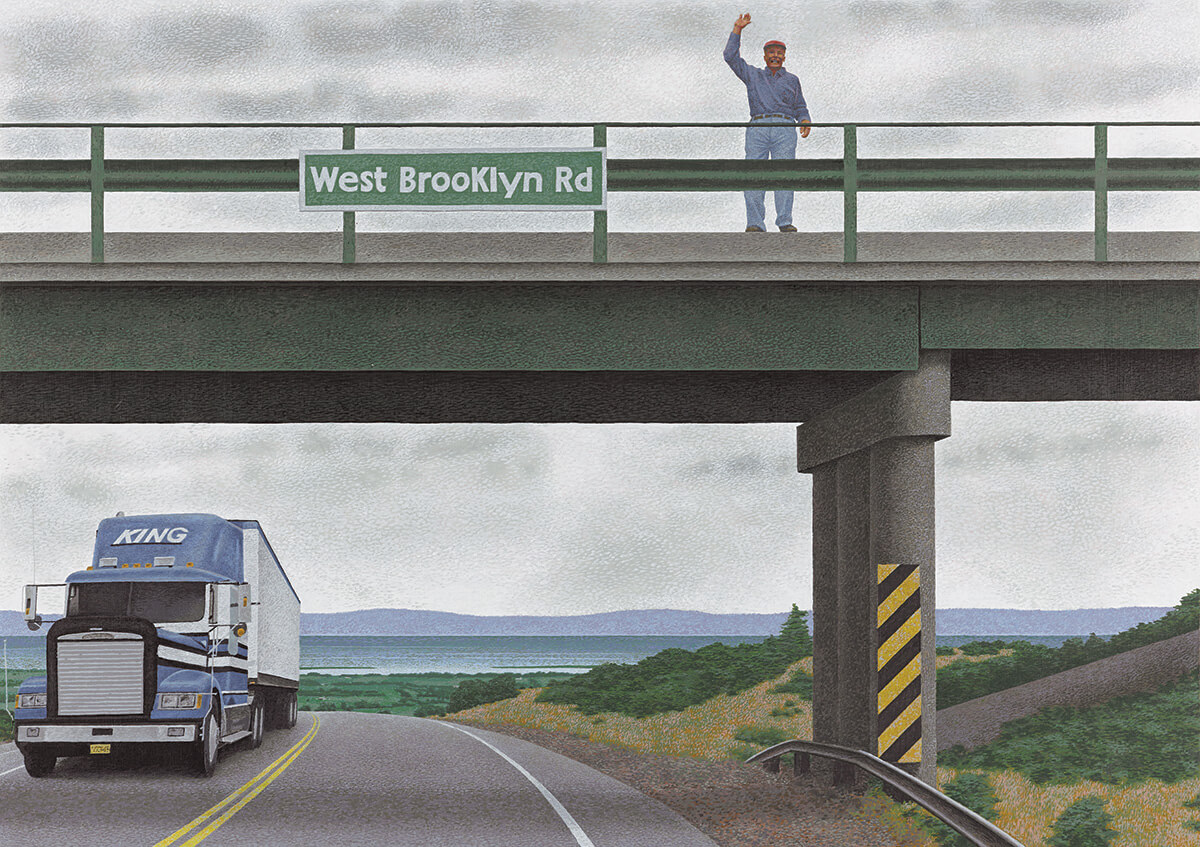

West Brooklyn Road 1996

Alex Colville, West Brooklyn Road, 1996

Acrylic polymer emulsion on hardboard, 40 x 56.5 cm

Private collection

Colville always sought the universal in the particular. In West Brooklyn Road he took an element from his day-to-day life and used it to build an image of startling power and symbolic impact. The scene is on Nova Scotia Highway 101, on what was then the first overpass between Hantsport and Wolfville. For years, an intellectually impaired man, Freddie Wilson, waved to drivers as they began the long turn into the Annapolis Valley.

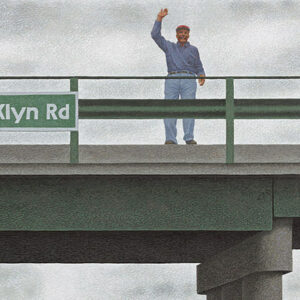

In West Brooklyn Road, though, the waver is not Wilson, but the artist. As such Colville presents an image of himself as a simple outsider watching the passing pageant of life. It is a self-deprecating image, unusual in Colville’s oeuvre, but one that reveals an important thread in his work—the self-knowledge of a man always aware of his personal ephemerality and refusing to take himself too seriously.

The viewpoint in this work is a common one in Colville’s paintings of the 1990s and later—that of a car driver or passenger. The scene also is fragmented, with the figure on the overpass looming impossibly large compared to the tractor-trailer in the oncoming lane. Colville reproduces the process of driving at speed: as viewers we note the oncoming truck, return our eyes to the road, then note the figure on the overpass. In the ensuing seconds the distances would have changed, but our impressions remain what they were when we first noticed the truck.

This work is reminiscent of another iconic Canadian painting, 401 Towards London No. 1, 1968–69, by Jack Chambers (1931–1978). Chambers positions the viewer at an overpass, looking down the highway as a large truck pulls away in the distance. The fixed perspective gives the painting its solidity. In contrast, Colville situates the vantage point from a moving vehicle, lending a feeling of slippage that undermines any sense of stability.

Colville isn’t portraying narrative time here. This image freezes a moment, one of comprehension and recognition. Each component—the overpass, the figure, the truck, the bay and horizon, the road snaking before our eyes—coalesces in a point outside of normal time, the instant when our brain catches up with our eyes. Clarity happens in our mind, not in the world.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements