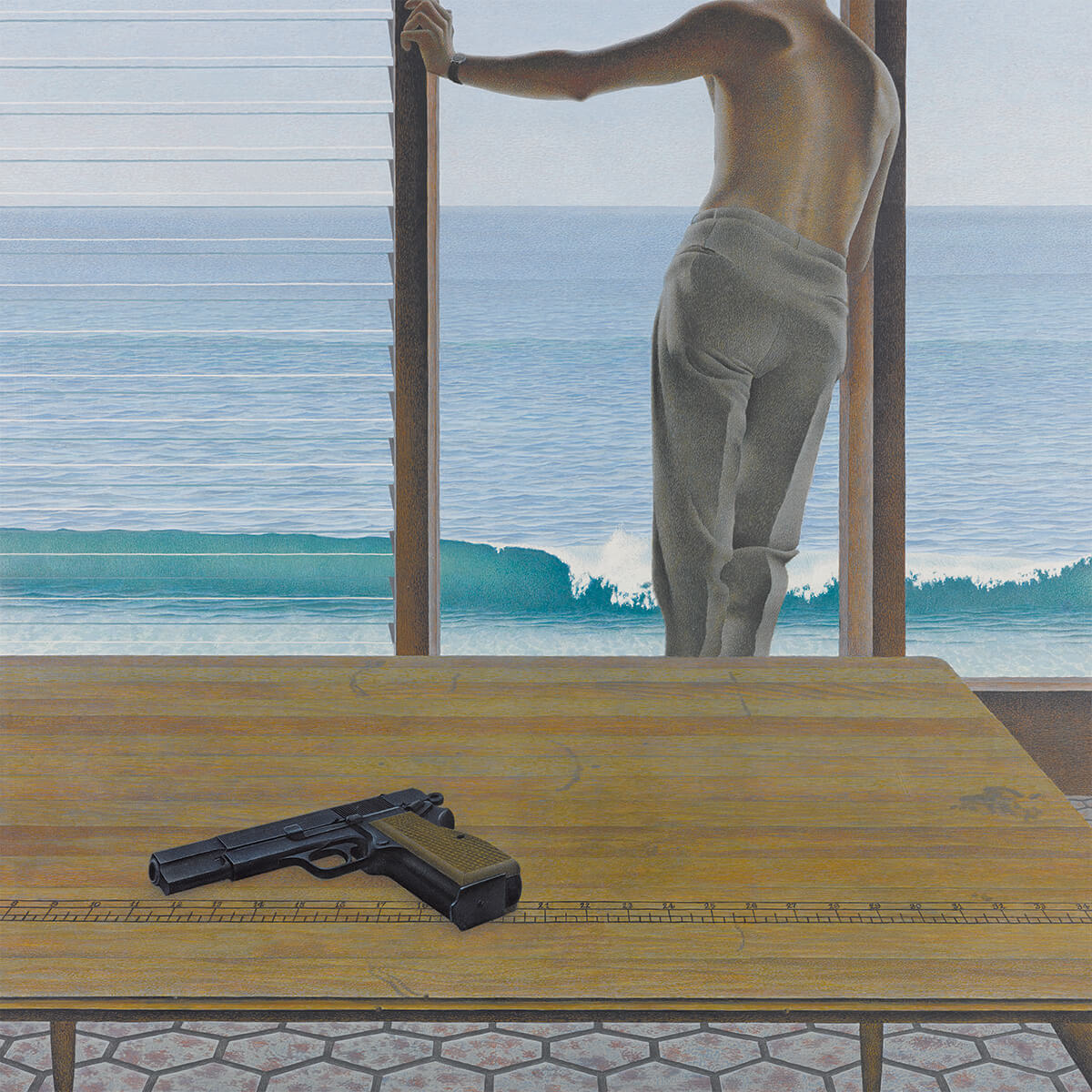

Pacific 1967

Alex Colville, Pacific, 1967

Acrylic polymer emulsion on hardboard, 53.3 x 53.3 cm

Private collection

This evocative image is one of Colville’s most overtly dramatic paintings since Horse and Train, 1954. It is one of few paintings by the artist depicting a land- or seascape that isn’t “home,” whether the environs of Sackville, New Brunswick, or Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Colville finished painting the scene during a six-month teaching position in Santa Cruz, California. It is simple yet powerful: a male figure looks out over an ocean, and a handgun lies on a wooden table that has a ruler embossed along one side.

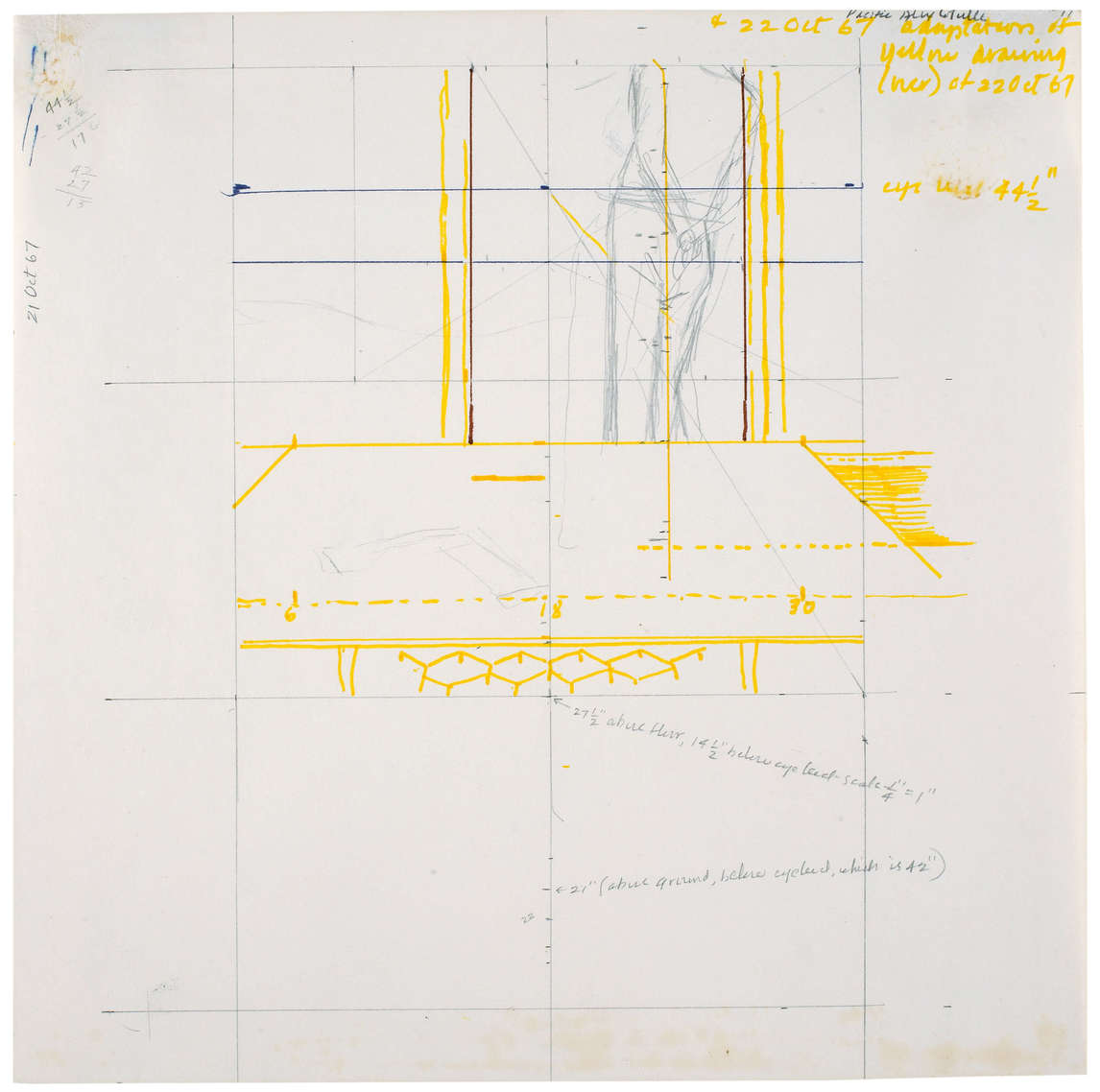

Like almost all of Colville’s work since Nude and Dummy, 1950, this painting is based upon a detailed skeleton of geometry; no component is placed randomly or as simply a reflection of observation. Two key elements were of great importance to Colville: the sewing table had belonged to his mother and the pistol was his Second World War service-issue sidearm. Colville constructed the image from various elements of his memory and experience, from sketches brought with him, and perhaps even from photographs. The foreboding presence of the handgun creates most of the tension in the work. The figure seems relaxed, the ocean is not particularly menacing, and there is nothing else in the room to add to or detract from the tension.

Colville was much influenced by French existentialism in the 1950s and 1960s, as were so many artists and thinkers of his generation. The works of Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) and Albert Camus (1913–1960) were particularly impactful. “It seemed enormously significant in a way I don’t think anyone could comprehend today,” he remarked. In formulating a moral and ethical response to the war, postwar thought was fraught with tension and trauma. Why should one not kill oneself in a world emptied of certainty and morality? Suicide was presented as a supreme act of will, if ultimately a futile one.

In Pacific, Colville creates an image of this moral dilemma, though the painting may represent a decision, as the turned-away figure implies a rejection. This may be a pause or a moment of reflection—“pacific” after all, means “peaceful”—and that is certainly one possible reading. Colville himself said, “I don’t think the painting is about suicide, I guess I think of the gun and the table as necessary parts of human life, upon which it is possible sometimes to turn one’s back.” Art historian Helen J. Dow reads the gun and the table with its built-in measuring rod as symbolizing justice—the sword and scales substituted by more prosaic emblems. Writer Hans Werner quotes Colville, agreeing with Dow’s interpretation and further reflecting on the use of the pistol as a meditation on power: “The use of power, [Colville] says, is a key moral and philosophical problem, and that’s what his paintings featuring pistols are about.” Whether this image is one of indecision or certainty, hope or despair, can only be decided by the viewer.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements