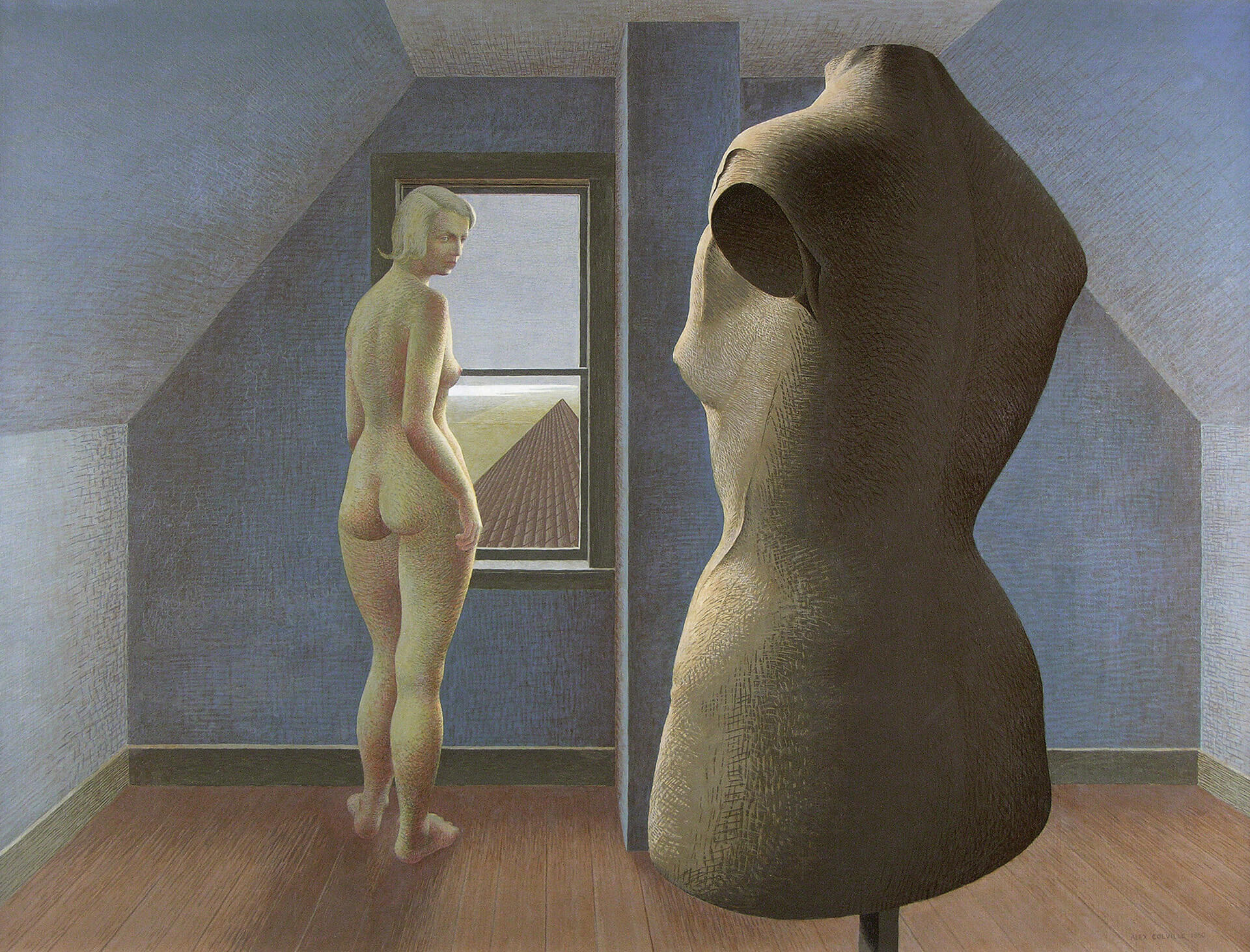

Nude and Dummy 1950

Alex Colville, Nude and Dummy, 1950

Glazed gum arabic emulsion on board, 76 x 99 cm

New Brunswick Museum, Saint John

Nude and Dummy was the first of Colville’s paintings to use the perspectival system that became his signature technique. Here, the painting’s elements are placed according to an underlying, meticulously constructed geometric skeleton rather than the more ad hoc and Impressionistic style he had learned at school and employed in much of his war art. It was also one of his first paintings sold to a museum (the New Brunswick Museum, Saint John), and the first sale of what he considered his mature work. To Colville, this marked his emergence as a serious artist: “I was therefore thirty years old before I did anything worthwhile.” Art historian Helen J. Dow, responding to this comment, writes, “This judgement is not based on the fact that he now received public recognition. Rather, it is an acknowledgement of his awareness of the mature handling of design and the sure understanding of the relationship between form and space achieved for the first time in this painting.”

The scene in Nude and Dummy is situated in an attic (the attic studio in Colville’s Sackville home), one strangely denuded of any objects except the lone female figure and a dressmaker’s dummy. Standing at the window, the nude woman looks back over her shoulder. She could be looking at the dummy or the artist (or his stand-in, us, the viewers). Her line of sight encompasses both.

The dummy is the disruptive element in this scene, a representation of the woman in the painting, yet a fragmented one, lacking head, arms, and lower body. It can be read as a mutilated body, adding a darker element to the work. That certainly has been the case in reviews of later work by the artist. In 1992 critic Shane Nakoneshny noted that “the women in [Colville’s] work (and some men) are often denied subjectivity, and their faces and hands are concealed.” While one might be tempted to read this work as an essay in the objectification of women, the cool look over the figure’s shoulder undermines any sense of her objectification.

This image demonstrates Colville’s interest in imbuing the everyday with heightened symbolic content, pairing a human figure with an object standing in for the figure—a binary relationship that would come to define his mature work. He was intrigued by the religious iconography of early European painting, when artists could expect their audiences to know the allegorical implications of a particular martyrdom or other scene from the Bible. As literary theorist Northrop Frye (1912–1991) so eloquently expressed it, the Bible was the “great code,” a common storehouse of ideas, symbols, and allusions.

In this and other Colville works of the 1950s one might perceive hints of his European counterparts in the Surrealist movement, such as René Magritte (1898–1967) or even Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), but Colville never admitted to such influences, if they existed. Rather, he stressed that he was seeking to avoid influence. Colville sets up a conversation in this image, a back and forth that refuses easy categorization or simple conclusion.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements