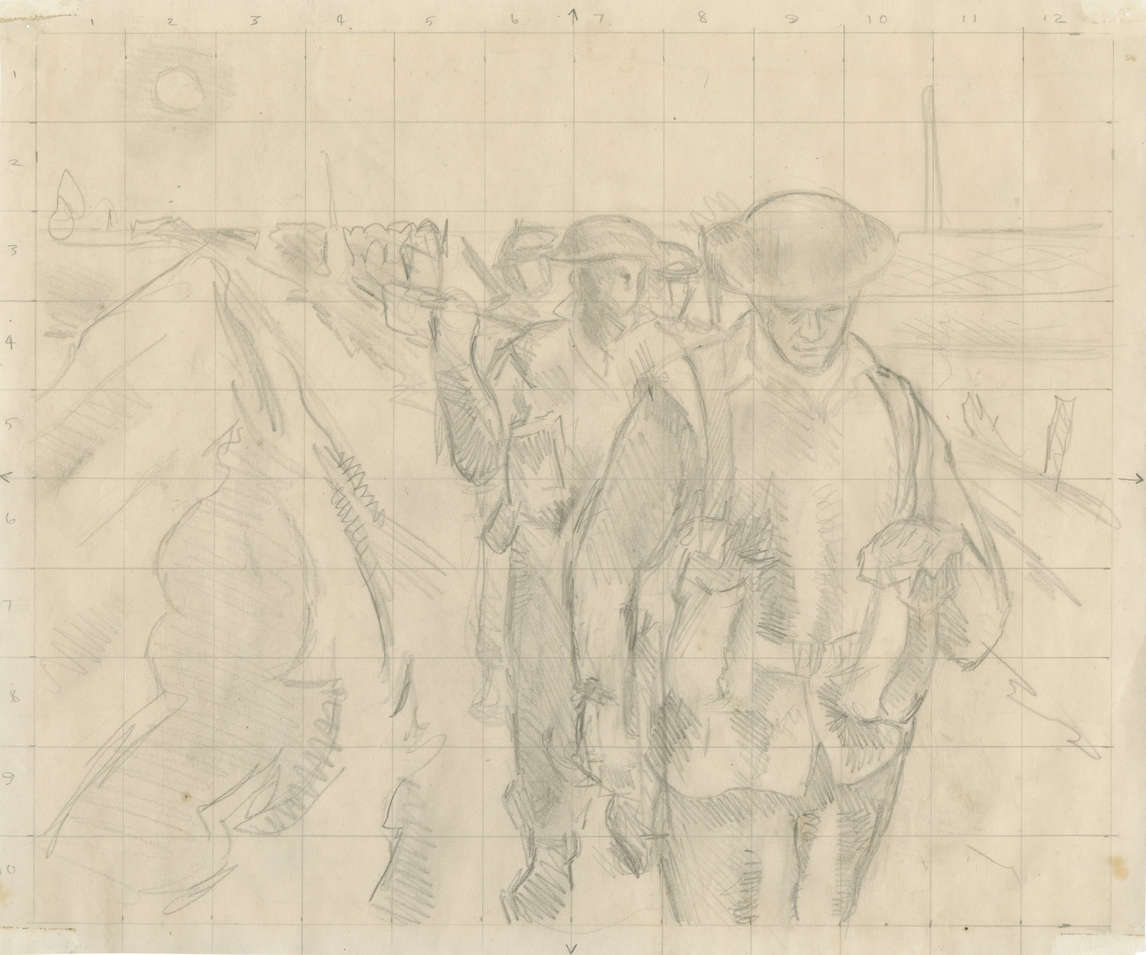

Infantry, Near Nijmegen, Holland 1946

Alex Colville, Infantry, Near Nijmegen, Holland, 1946

Oil on canvas, 101.6 x 121.9 cm

Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa

Colville’s early work was produced while he served as an official war artist in the Second World War. Having gone straight from being a student at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, to joining the army, Colville did not think that his production during the war years really reflected his eventual development as an artist. He has been widely quoted as feeling that he didn’t make his first mature work until 1950, four years after painting this image from sketches completed in 1945. However, this painting foreshadows many concerns seen in his more mature work.

The composition, for instance, reflects the geometric obsessions of Colville’s later work, with a strong diagonal form cutting across the canvas, from upper left to lower right of the picture plane. Canadian soldiers walking through the mire of the Scheldt estuary in Holland are depicted as a series of plodding figures receding into the background, their collective weight seeming to push the figure in the foreground from his position in the lower right-hand corner out into our view. Colville has adopted the viewpoint of the next man ahead in line, looking back as he negotiates a gentle turn indicated by the water-filled furrow that parallels their marching path.

Gently curving diagonal lines often appear in Colville’s compositions, such as Horse and Train, 1954, Soldier and Girl at Station, 1953, West Brooklyn Road, 1996, and Traveller, 1992. This technique breaks up the rigid geometry of the composition, introducing an element of softness to the hard lines that underlie all of Colville’s images. Painted in Ottawa after his return from overseas, this is a composite image: the hands of the lead figure were based on the artist’s own, while the face was based on that of his father: “I thought of my father as a kind of a corporal,” Colville said.

Along with Infantry, Near Nijmegen, the Canadian War Museum holds in its collection of Second World War art hundreds of paintings, drawings, and watercolours by Colville. While this work lacks the drama of Horse and Train and others of the 1950s, it contains the seeds of Colville’s concern with the place of humans in a shattered world. These figures proceed by force of will—set in motion by the orders of others but sustained only through their own individual agency.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements