Centennial Coins 1967

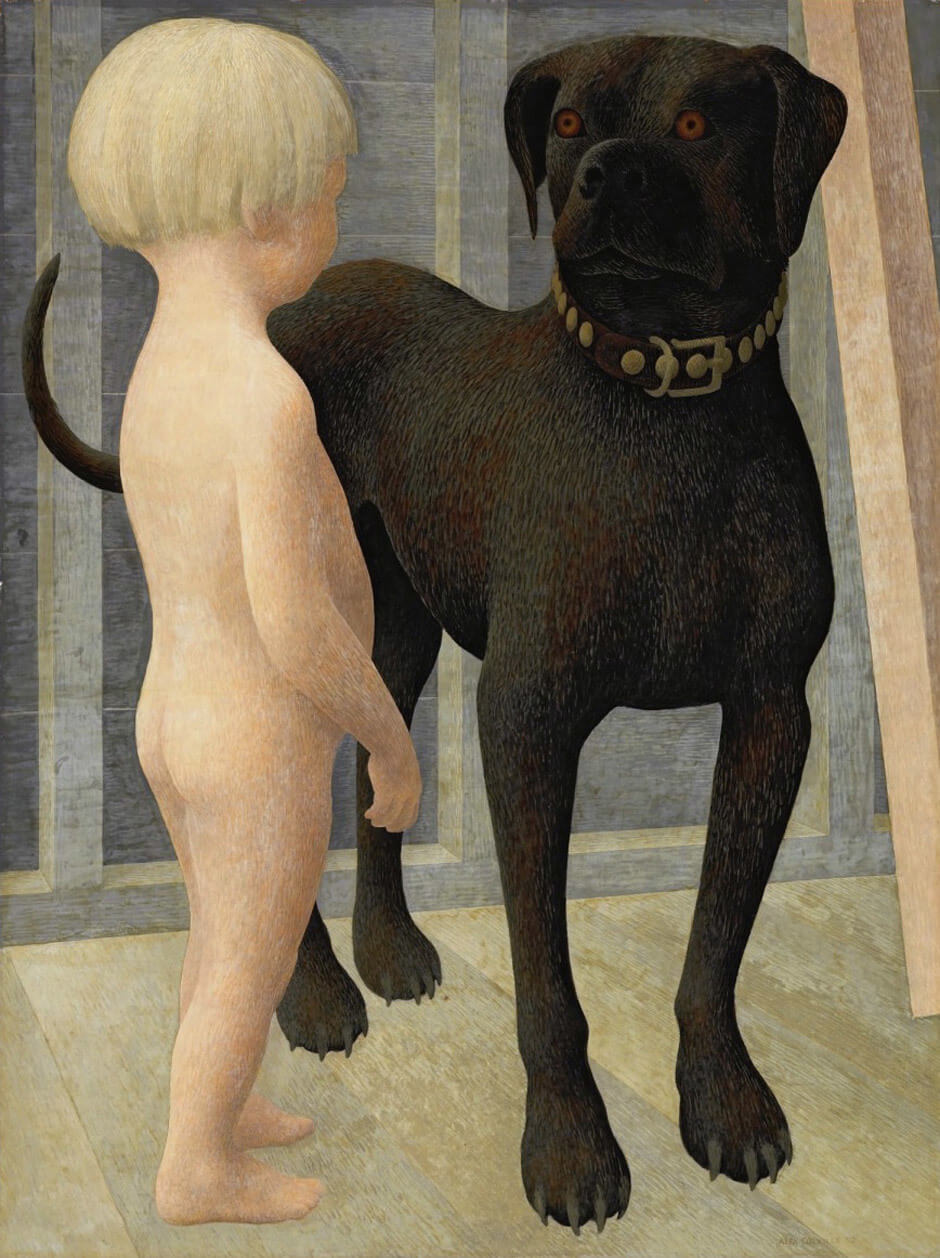

Alex Colville, Centennial Coins, 1967

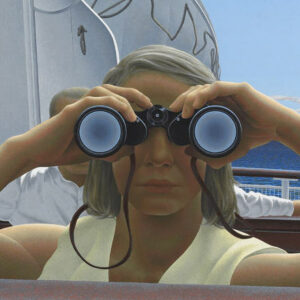

LEFT: Colville Mackerel 6066 (Dime), 2013

Pigment print flush mounted to archival board, 40 x 40 cm

Stephen Bulger Gallery, photograph by William Eakin

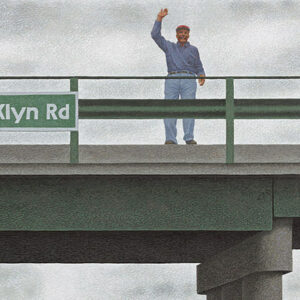

RIGHT: Colville Wolf 6275 (Half Dollar), 2013

Pigment print flush mounted to archival board, 40 x 40 cm

Stephen Bulger Gallery, photograph by William Eakin

“I do not find life boring or banal. Consequently I am not in flight from what might be called ordinary experience,” Colville said. What could be more ordinary than pocket change, and what series of artworks have had the reach of Colville’s centennial coins, which for decades showed up regularly in Canadians’ change purses and wallets. The six coins that made up the series—depicting a Canada Goose (one dollar), a wolf (fifty cent), a wildcat (twenty-five cent), a mackerel (ten cent), a rabbit (five cent), and a dove (one cent)—can be thought of as the largest-edition Canadian artwork ever made and the most widely disseminated.

In 1965 Colville submitted designs for centennial coins, following a call from the Royal Canadian Mint in celebration of Canada’s 100th anniversary of Confederation. The mint, which had requested submissions from several artists, was so taken with Colville’s simple designs of common Canadian animals that he won the commission for the entire set. Colville, whose first introduction to art as a teenager involved carving and drawing, made the most of the shallow relief format of the coins to exploit the sculptural qualities so apparent in his work by the mid-1960s. His painted images have a weighty solidity despite their essential flatness, and one can easily see how they would translate well to the shallow-relief forms of coins and medallions.

He chose animals because, as he wrote in a statement for the mint, “It is a question of finding images which are worthy and appropriate for use in celebrating our country’s Centennial, images which will express not merely some particular time, place, or event, but a whole century of Canada, and even more; natural creatures provide this enduring and meaningful continuum.” Animals were a staple in Colville’s mature work, from the horses and dogs of works such as Horse and Train, 1954, and Child and Dog, 1952, and he consistently included cows, sheep, crows, and other animals until his death. He said of his use of animals, “To me the presence of animals seems absolutely necessary. I feel that without animals everything is incomplete.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements