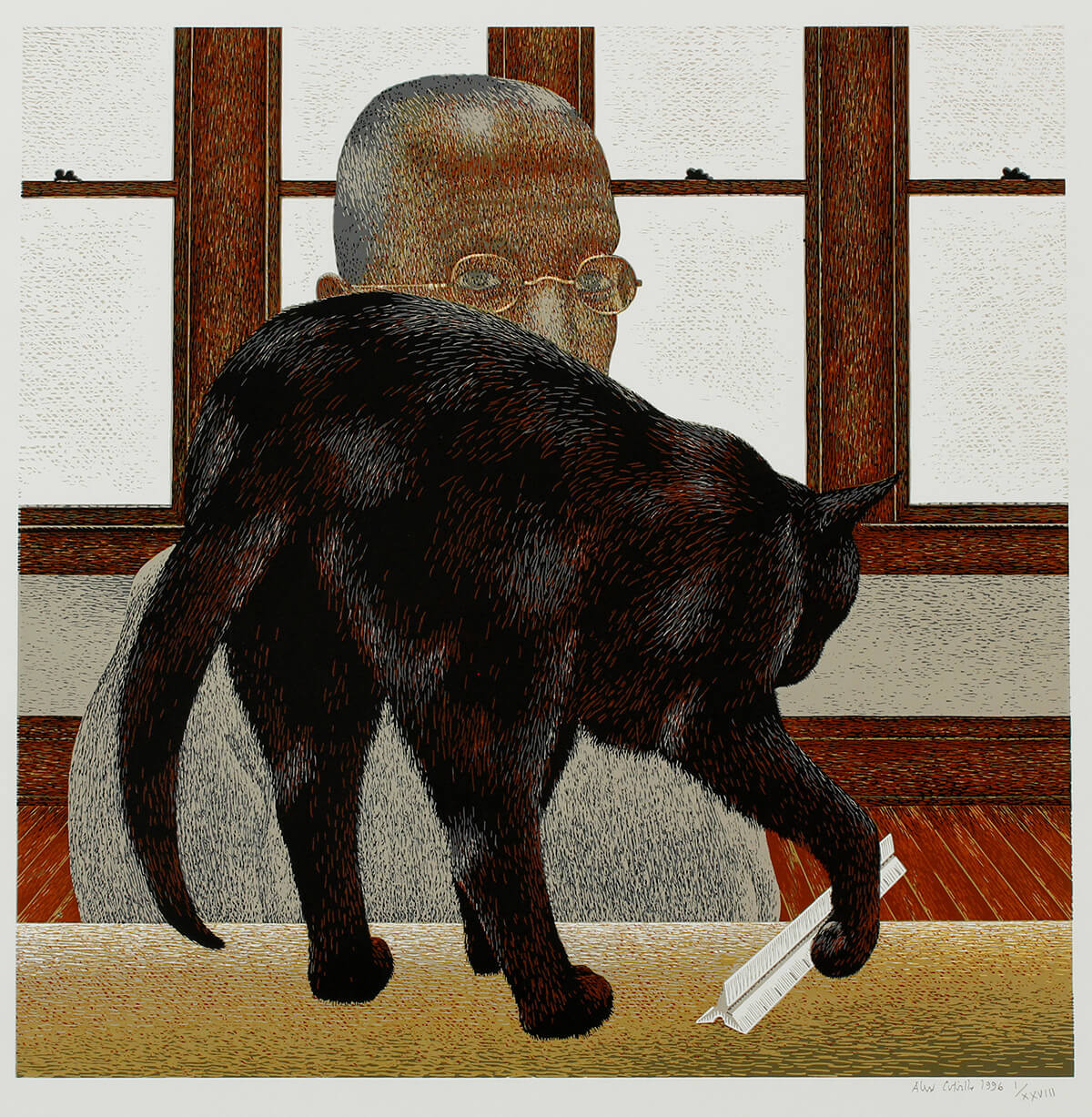

Black Cat 1996

Alex Colville, Black Cat, 1996

Serigraph on paper, edition of 70, 36 x 36 cm

Owens Art Gallery, Mount Allison University, Sackville

A process in which he was self-taught and which he did on his own, never working with printers, serigraphs were an important part of Colville’s practice.1 Prints were a way of reaching a larger audience and presented a set of physical and intellectual challenges that were different from painting and demanding in their own way. “I think there is always a tendency for the print to be directed to a wider public,” he observed.2

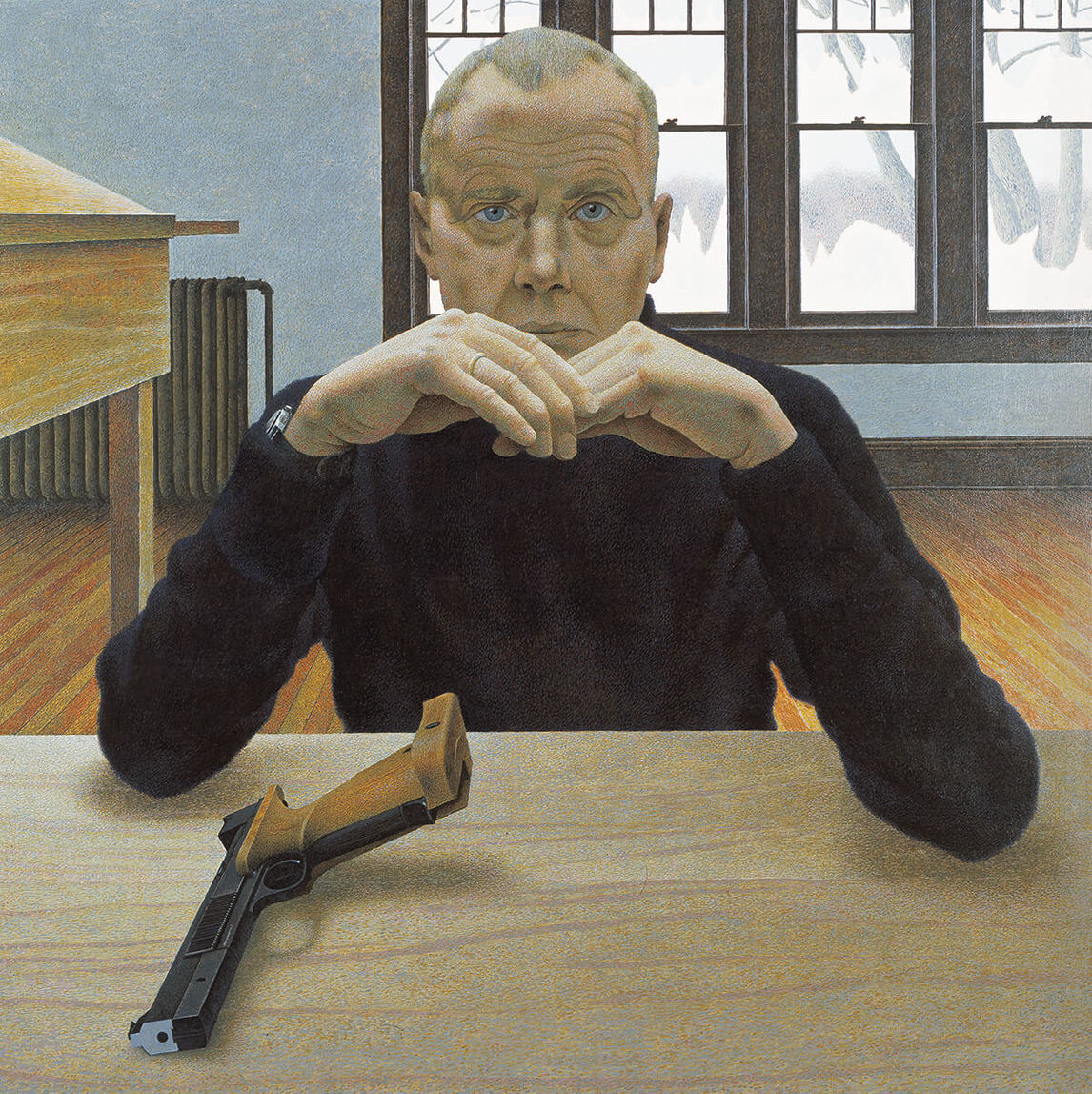

Black Cat, a relatively late print, is remarkable for integrating several themes important to Colville: the role of the artist, the dichotomy between human and animal worlds, and the precariousness of order in the face of time and chaos. In composition the painting reprises Target Pistol and Man, 1980, which positions the artist in a near-identical setting. Perhaps more than any other of Colville’s works, Black Cat addresses his use of geometry to create order and evoke the inherent fragility of that construction.

As an artist who uses his immediate surroundings, in particular his home and family, as a source of his imagery, it is not surprising that Colville also employs the genre of self-portrait. However, most often Colville, like his wife, Rhoda, or his daughter, Ann, appears to be a character more than a precise representation of himself. The male figures in Ship and Observer, 2007, or Kiss with Honda, 1989, for instance, are both based on Colville but not in self-observation or self-scrutiny. Black Cat, however, differs as a more traditional method of self-portraiture.

In this work the artist looks directly at the viewer, the lower half of his face obscured by a cat toying with a triangular ruler in front of him on a table. Animals in Colville’s paintings and prints serve as a foil to humans, as seen in an earlier serigraph, Cat and Artist, 1979, and in paintings such as Dog in Car, 1999, and Headstand, 1982, among many other examples. They do not strive for meaning or seek answers. As author Tom Smart observes, for Colville, “the cat is the emblem of unknowing.”3 The ruler may be the focal point of the composition, but for the black cat, its function is irrelevant; it is an object to play with. The cat’s complete otherness undermines the underlying web of geometry that holds this, and every, Colville image together—order is simply irrelevant in the cat’s world. But for the artist, that geometry symbolized by the ruler is a device for creating order out of chaos, certainty out of mystery, and knowledge out of ignorance.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements