Agnes Martin’s approach to painting can be separated into two long periods divided by a seven-year hiatus between 1967 and 1974. The first, from 1946 to 1967, is characterized by explorations into different approaches to abstraction. The decades between 1974 and her death in 2004 represent an investigation into the creative potential of a single format—square canvases of consistent size with either horizontal or vertical lines or bars. Within these major phases, her work can be categorized into briefer periods, one as short as four years, through which we can chart Martin’s evolving style and the technique behind her canvases.

Early Works: 1946–1957

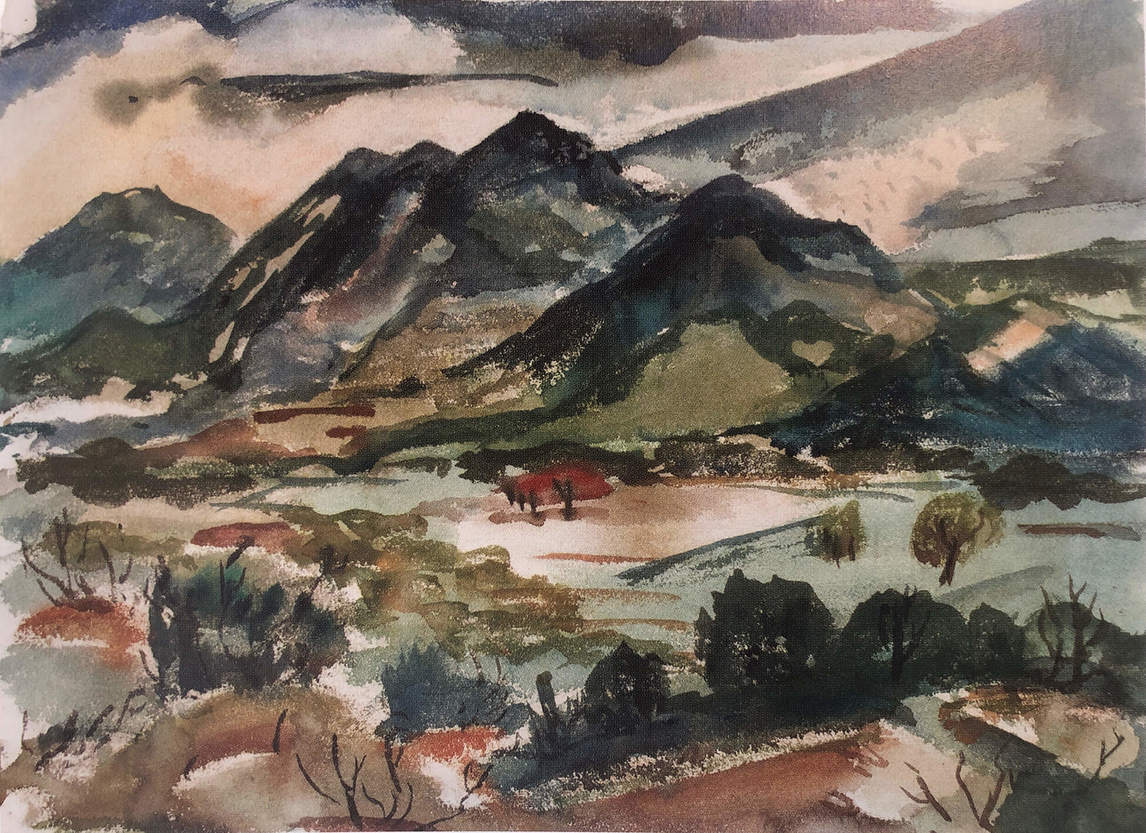

Although Agnes Martin started painting while studying at Teachers College at Columbia University in New York in 1941 and 1942, no artworks remain from this period, nor from the four subsequent years that she spent as an itinerant teacher throughout the American West.1 Martin meticulously and methodically found and destroyed her early paintings, making an assessment of the beginning of her career difficult. The earliest extant works by Martin date from the two years that she spent at the University of New Mexico between 1946 and 1948, first as a student and then as a teacher. They were produced in the context of the classes that she was taking or teaching and do not point to a consistent style. An encaustic still life of a vase of flowers on a bench may have been completed as a component of her entrance exam in 1946; three watercolour landscapes of the Taos valley were realized during the 1947 Taos Summer Field School session; and four portraits, one of herself and three of friends and acquaintances in Albuquerque, may date to a class in portrait painting Martin taught in the fall of 1948.

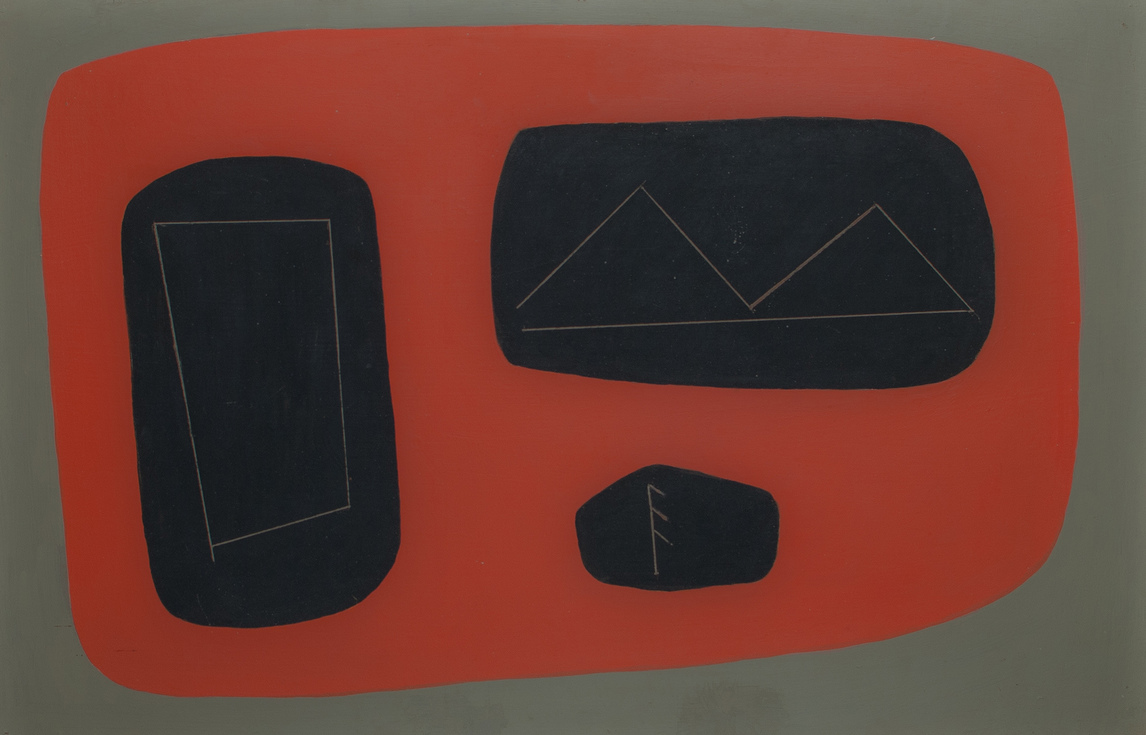

There are several works on paper that date to her time pursuing a master’s degree at Teachers College at Columbia in 1951 and 1952, including Untitled from 1952. These works show a strong influence of automatism, a technique developed by the Surrealists and utilized by the Abstract Expressionists to draw or paint while suppressing conscious control in an effort to allow the subconscious to take over. Two early abstract paintings have been dated c.1949, which means that Martin may have begun painting in a non-objective style while teaching in New Mexico public schools before moving back to New York in 1951.2 One, Untitled, c.1949, shows a deconstructed landscape with simplified symbols for a tree, two mountains, and a lake traced in black shapes that float on an orange and green background.

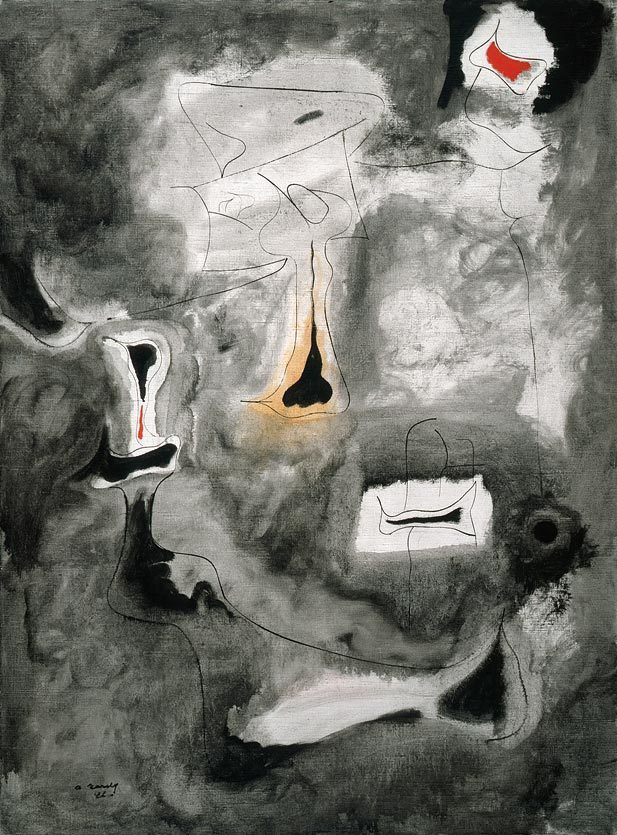

But it was not until 1953, when Martin was back in Taos, that we can say she started developing an abstract style of her own within a group that became known as the Taos Moderns. The period, generally termed her biomorphic period because it featured floating curvilinear and organic-like forms, continued until 1957, when she moved back to New York. Biomorphism is a variety of abstraction where forms are derived from organic shapes, as opposed to the ridged shapes found in geometric abstraction. It was prevalent amongst the Abstract Expressionists in New York in the 1940s, as seen in the work of Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), Arshile Gorky (1904–1948), and Mark Rothko (1903–1970), all admired by Martin at this time. Critic Lawrence Alloway described biomorphism as the “invention of analogies of human forms in nature and other organisms,” and it was introduced to New York through European Surrealists such as Jean Arp (1886–1966) and Joan Miró (1893–1983), among other sources such as Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), more than a decade before Martin picked it up.3

Only fifteen oil paintings on canvas and some works on paper can be dated to this period. The canvases are all rectangular, almost all of them in landscape orientation (wider than they are high), and they are of varying sizes. They often feature Surrealist-like black lines, possibly the result of automatic drawing, and biomorphic forms floating over a light background. Comparing Martin’s The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, c.1953, to Charred Beloved II, 1946, by Arshile Gorky reveals a similar melding of abstract brush strokes and a wandering line.4 Martin’s painting The Bluebird, 1954, features the eponymous animal in the lower right corner. It is the last referential form that Martin painted.

Before the Grid: 1957–1961

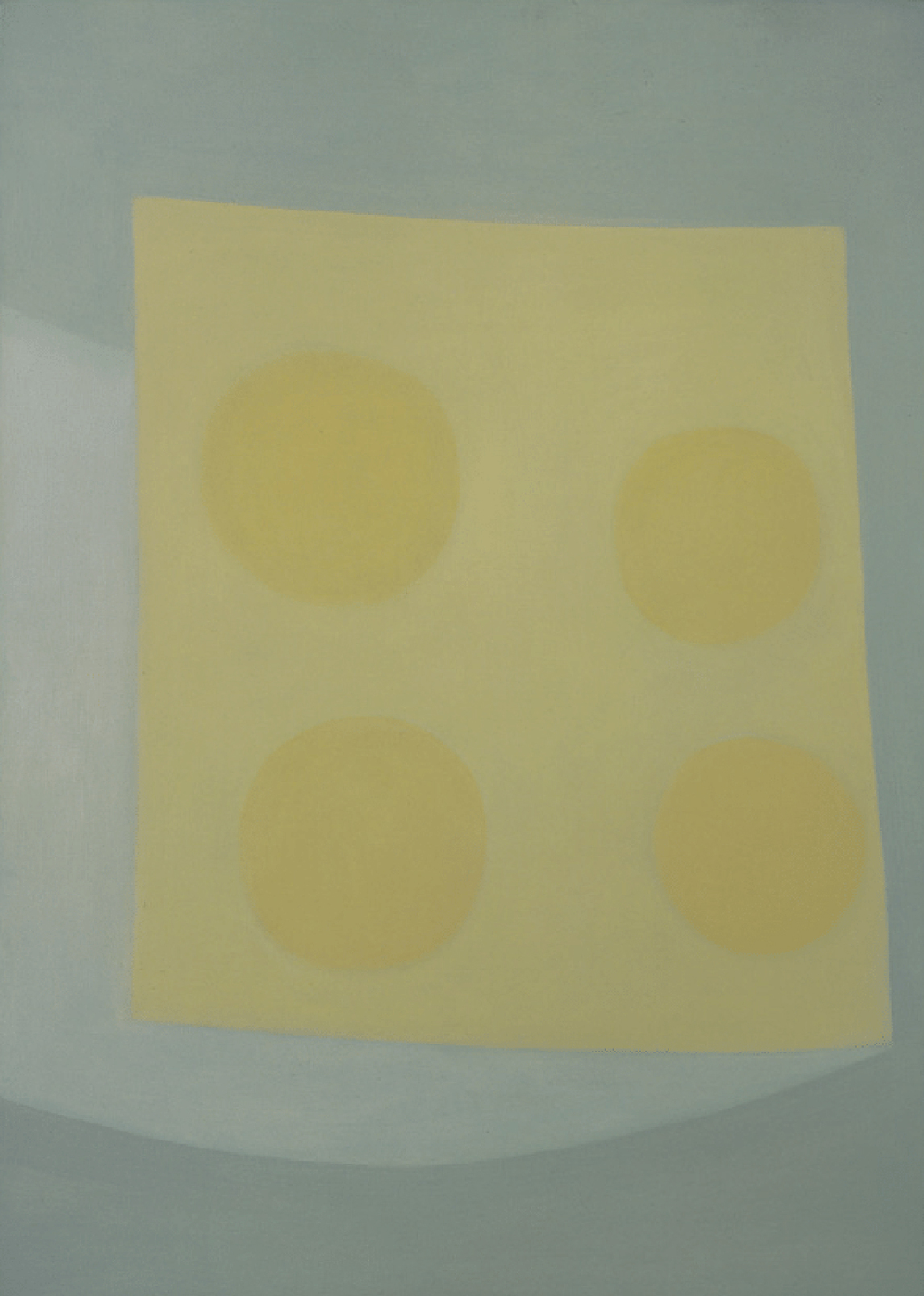

Martin’s approach to abstraction changed quite quickly after she returned to New York in 1957, this time not as a student but as an artist. Dancer No. I (L.T.), painted in Taos around 1956 and likely finished in New York in 1957 or 1958, can be seen as a transitional painting between her Taos and early New York styles. The biomorphic shapes of the Taos period can be seen throughout the canvas. A yellow square with four roughly symmetrical circles in the top right quadrant of the painting, on the other hand, indicates the more geometric style that Martin was fostering during her first year in the city. In Drift of Summer, 1957, she zooms in on the yellow square from Dancer No. I (L.T.), making it the focus of the painting. Over the course of two paintings, she abandoned biomorphic form and replaced it with a simple geometric shape.

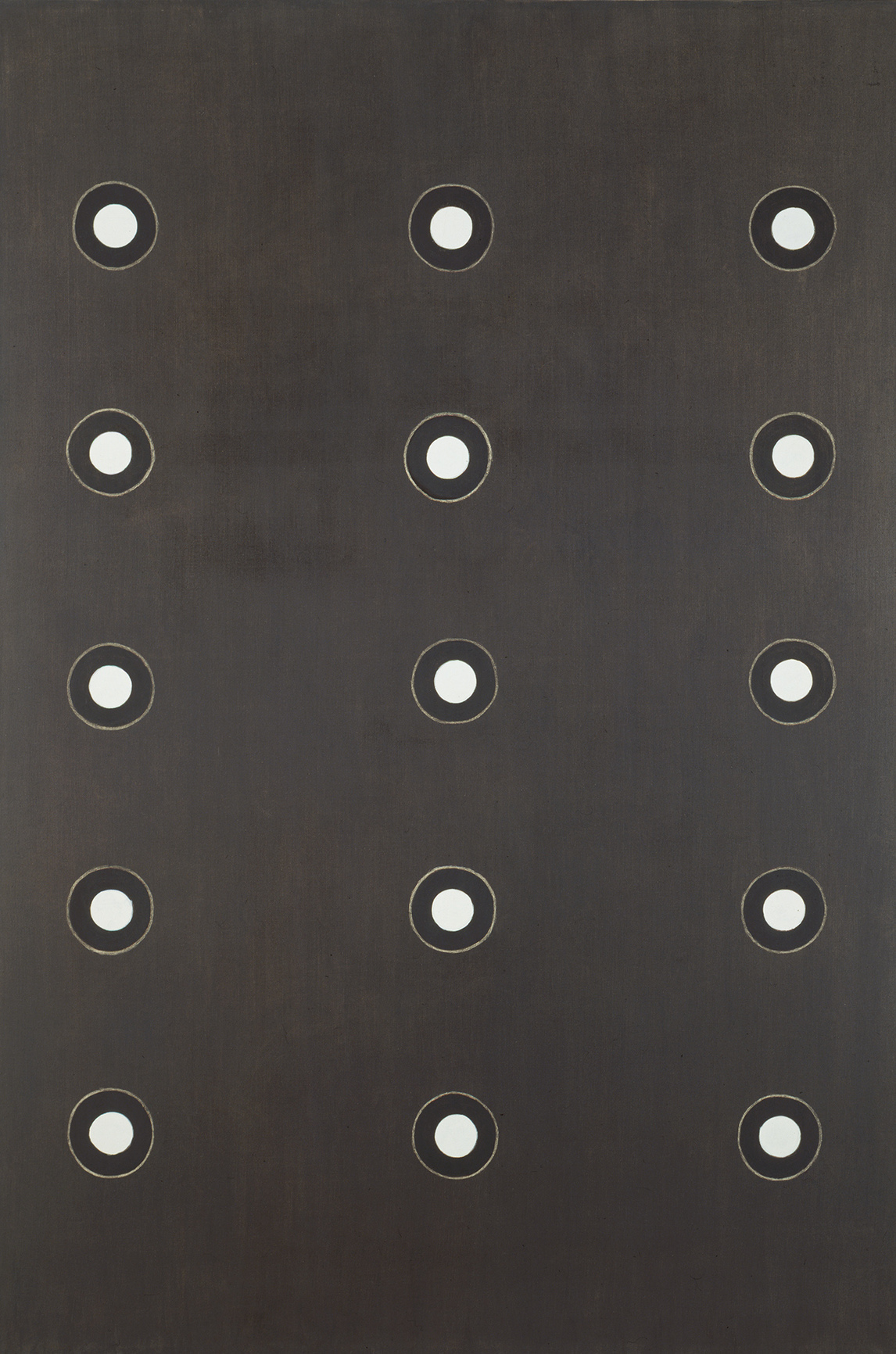

The yellow square led to a series of similarly shaped canvases, introducing a format to her practice that included The Spring, 1958, which was exhibited alongside Dancer No. I (L.T.) and Drift of Summer in her first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1958. For her second exhibition with Parsons, Martin further developed her analysis of the rectangle and the circle, expanding the simple grid of four circles to a larger grid of twenty-five circles, with five rows of five, in the painting Earth, 1959. Reflection, 1959, from the same exhibition, featured five rows of three white circles over a dark background.

Martin experimented extensively with canvas size, material, and technique between 1958 and 1961. Most of the works from these years are oil on canvas, although she did work in assemblage and ink on paper. Many of the canvases from these exhibitions had natural palettes of brown, yellow, and grey, and had titles such as Desert Rain, 1957, and Water, 1958. At her final exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1961, Martin exhibited her first true grid paintings, replacing circles with lines of oil or graphite on canvas.

The New York City Grid: 1961–1967

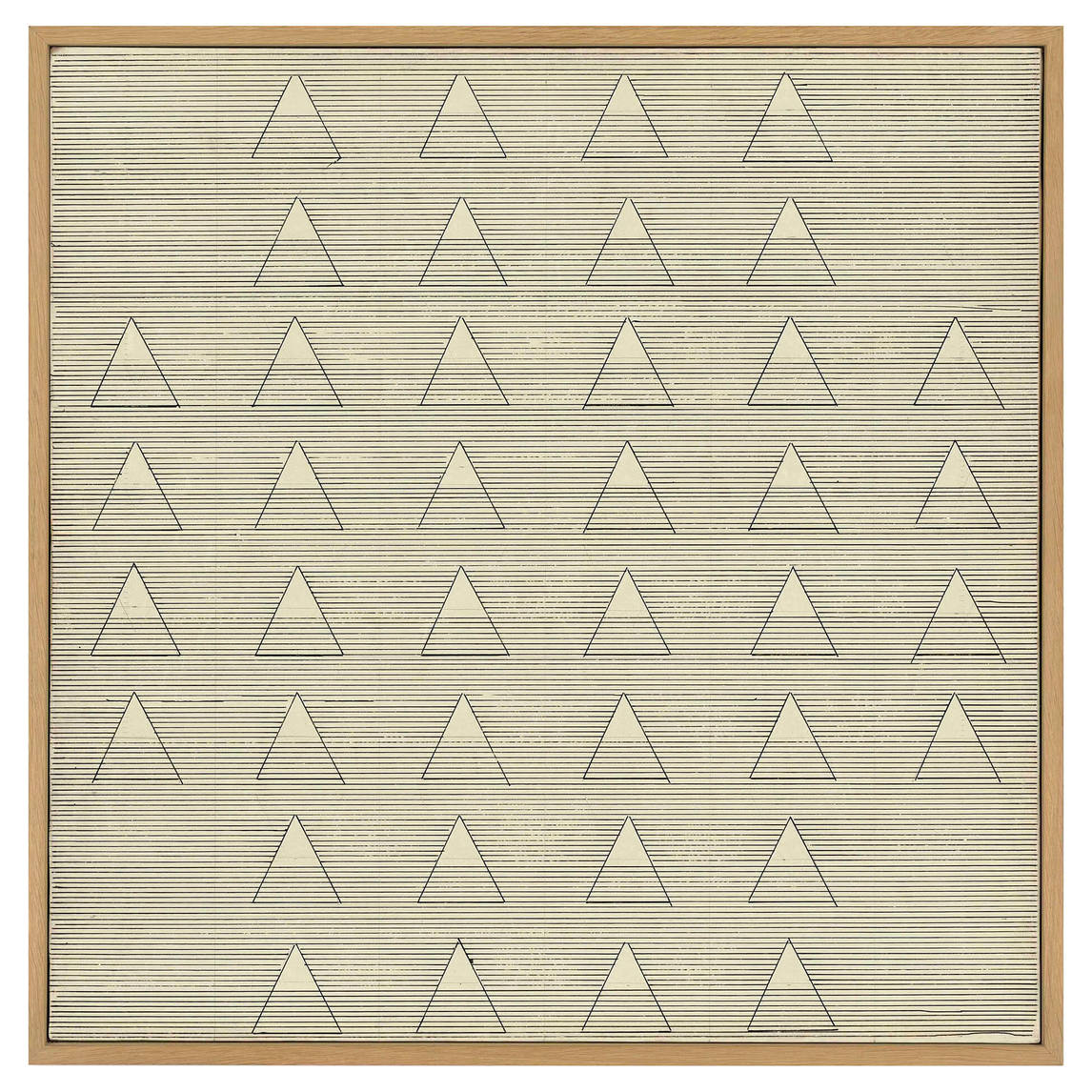

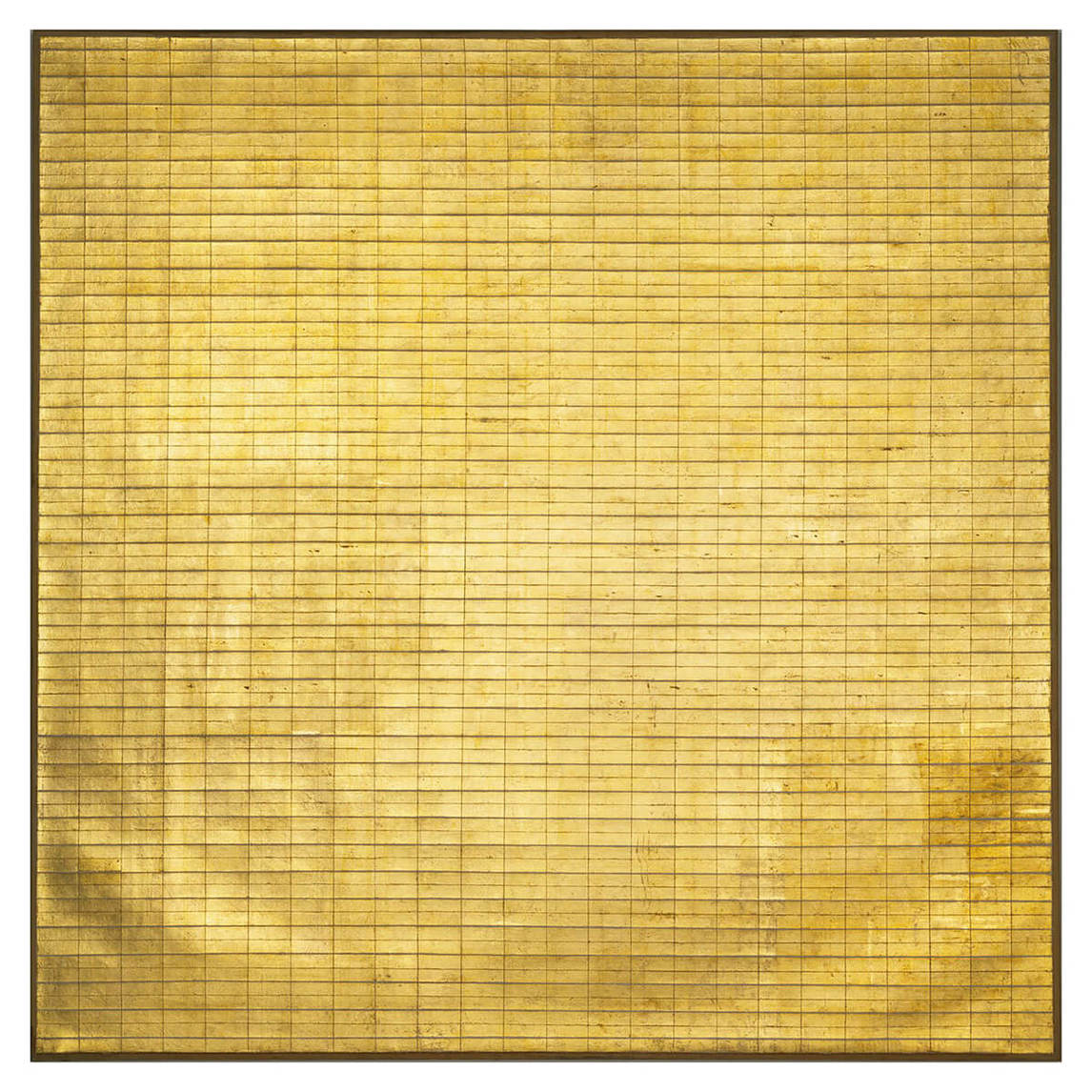

For the first three years of the 1960s Martin continued to explore different media to probe the creative potential of the grid format. The grid was an organizing structure for Martin, within which she could experiment with colour, form, and shape. White Flower, 1960, is an oil painting with a rectangle and dash pattern on a six-foot-square canvas, one of the first paintings of that size. Untitled, 1960, from the same year, has a similar rectangle and dash pattern but is made up of graphite, oil, and ink on a one-foot-square raw canvas. Words, 1961, on the other hand, has a grid of pyramids and horizontal lines on a two-foot-square paper mounted on canvas. Martin also used some unconventional painting materials during this time. The Wall #2, 1962, has a dot and rectangle pattern of oil and ink on canvas mounted on wood, but the dots are nails tacked onto the wood through the canvas. Two paintings from 1963, Friendship and Night Sea, are covered in gold leaf. Perhaps the most unorthodox work from this period is The Wave, 1963, an edition of five wood and coloured Plexiglas boxes with grids scored into their bottoms. Each box contains over a dozen small beads that roll and settle along these lines like a children’s toy.

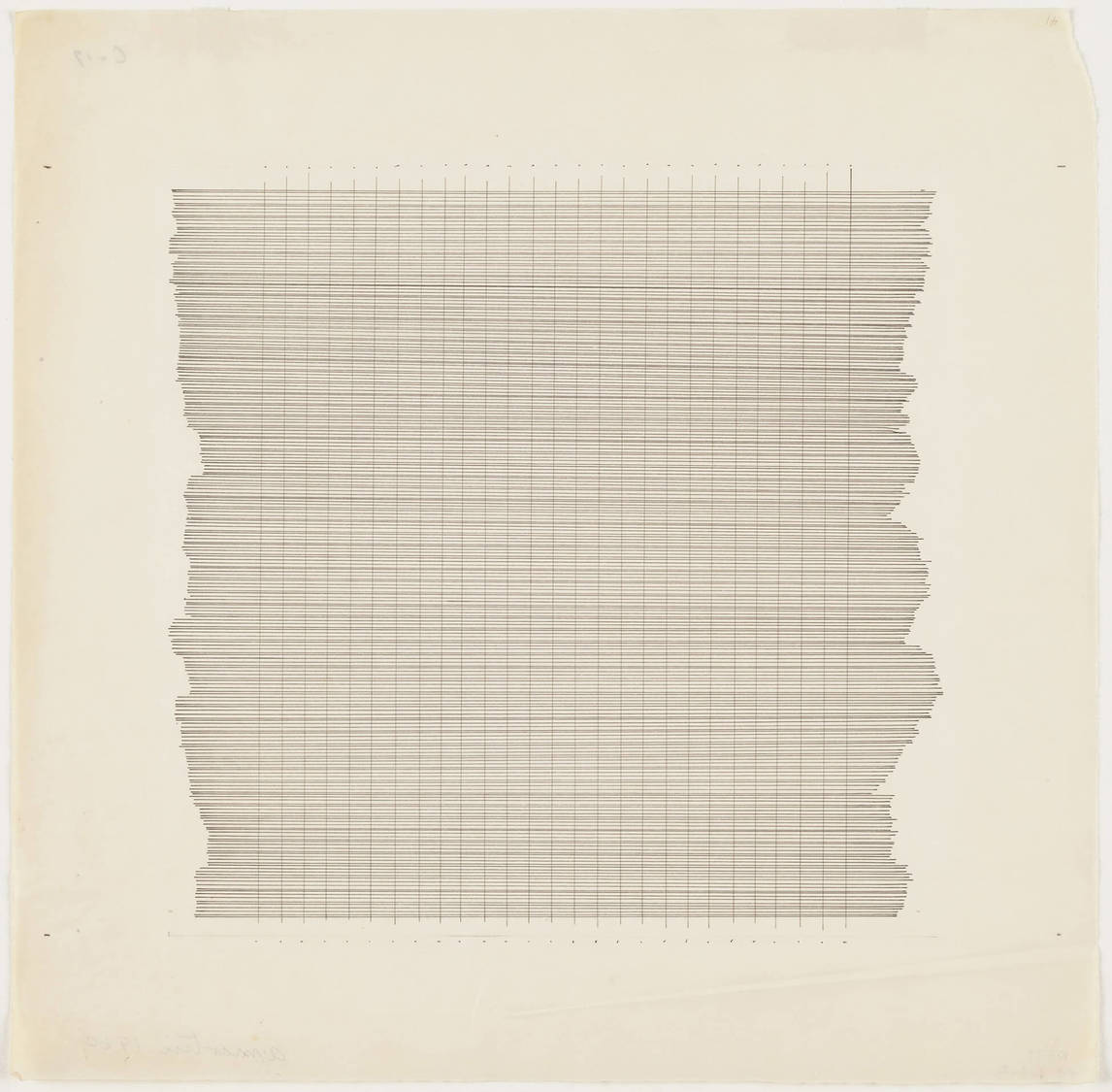

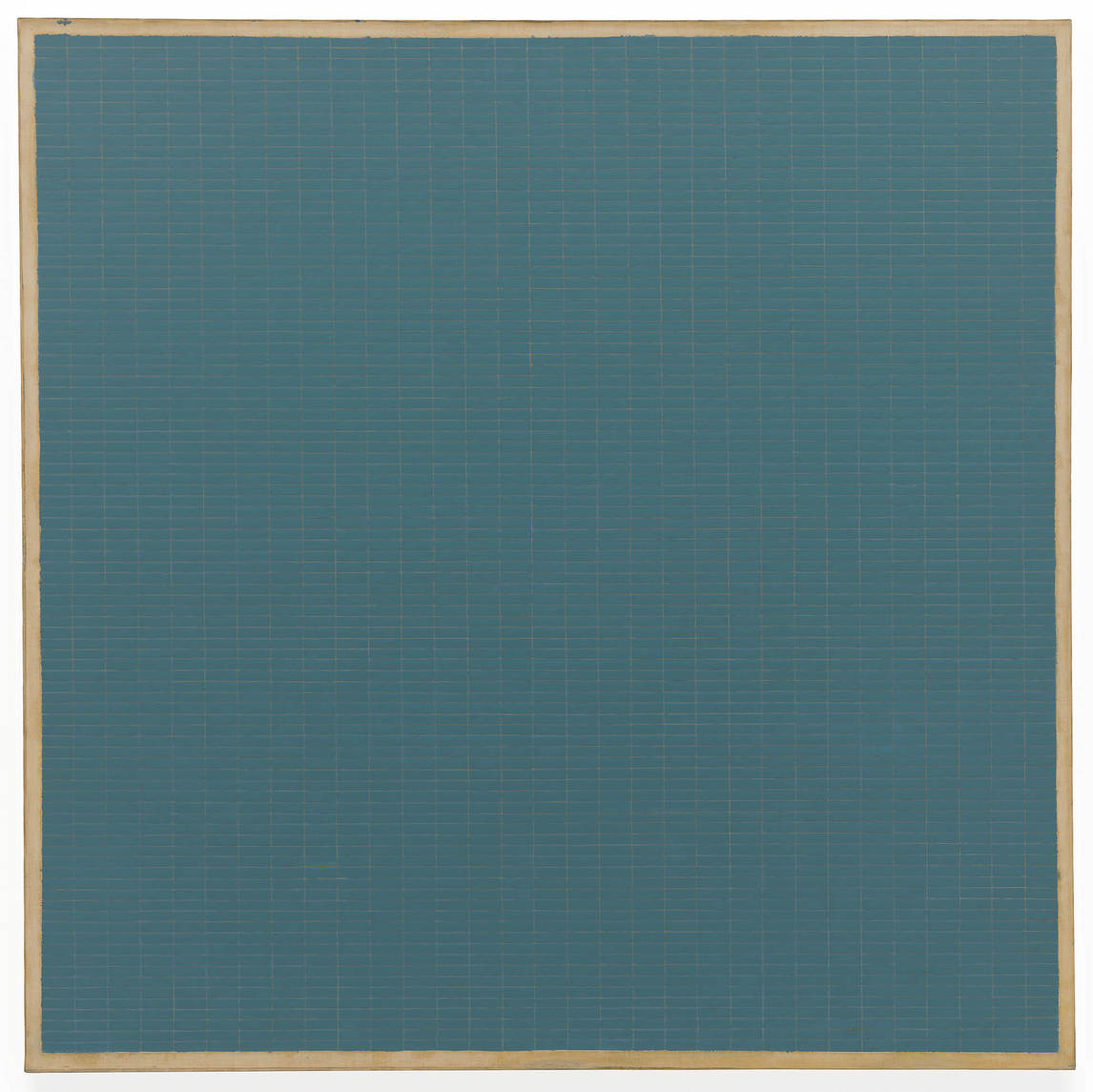

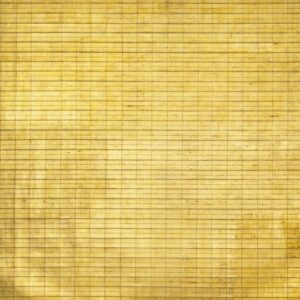

In 1964 the grid paintings became much more consistent in size, material, and technique. All of the canvases dated to that year were six feet square, either oil or acrylic with graphite or coloured pencil. Martin also worked in smaller-scale drawings, some as small as eight inches square as, for example in Untitled, 1963. Art historian Briony Fer argues that although the scale of her paintings and drawings differed, Martin did not distinguish between the two, using the same techniques, materials, and forms in both formats.5 In a review of Martin’s exhibition at Robert Elkon Gallery in 1965, Jill Johnston described the grid as “absurdly simple,” with the “the quiet intensity of a perfectly contained image that moves in and around itself without moving at all.”6

Martin often started her painting process by sitting in her chair with a clear mind, waiting for inspiration. Each band, bar, or line was carefully planned out in advance using intricate mathematical equations on sheets of paper in her studio. Only after she had worked out the composition would she attempt it in a larger format, first by covering the canvas in oil or acrylic paint with a brush, then by drawing graphite lines using a short T-square and a string to guide her hand. The result, which can be seen in The Rose, 1964, for example, is often minuscule imperfections in each line where she lifted the pencil to move the T-square. After 1966 Martin predominantly used acrylic paint.7

Horizontal and Vertical Bands: 1974–2004

The twenty years before Agnes Martin’s sudden departure from New York in 1967 were full of stylistic and technical experimentation. The thirty years that followed her return to painting in New Mexico in 1974 after a hiatus of seven years, on the other hand, can be described as a meticulous exploration of the creative potential of a single style. Between 1974 and 1993 Martin painted almost all of her paintings on six-foot-square canvases using acrylic. She produced the occasional small canvas, generally one foot square, and also worked in watercolour on paper, usually at a size of nine inches square.

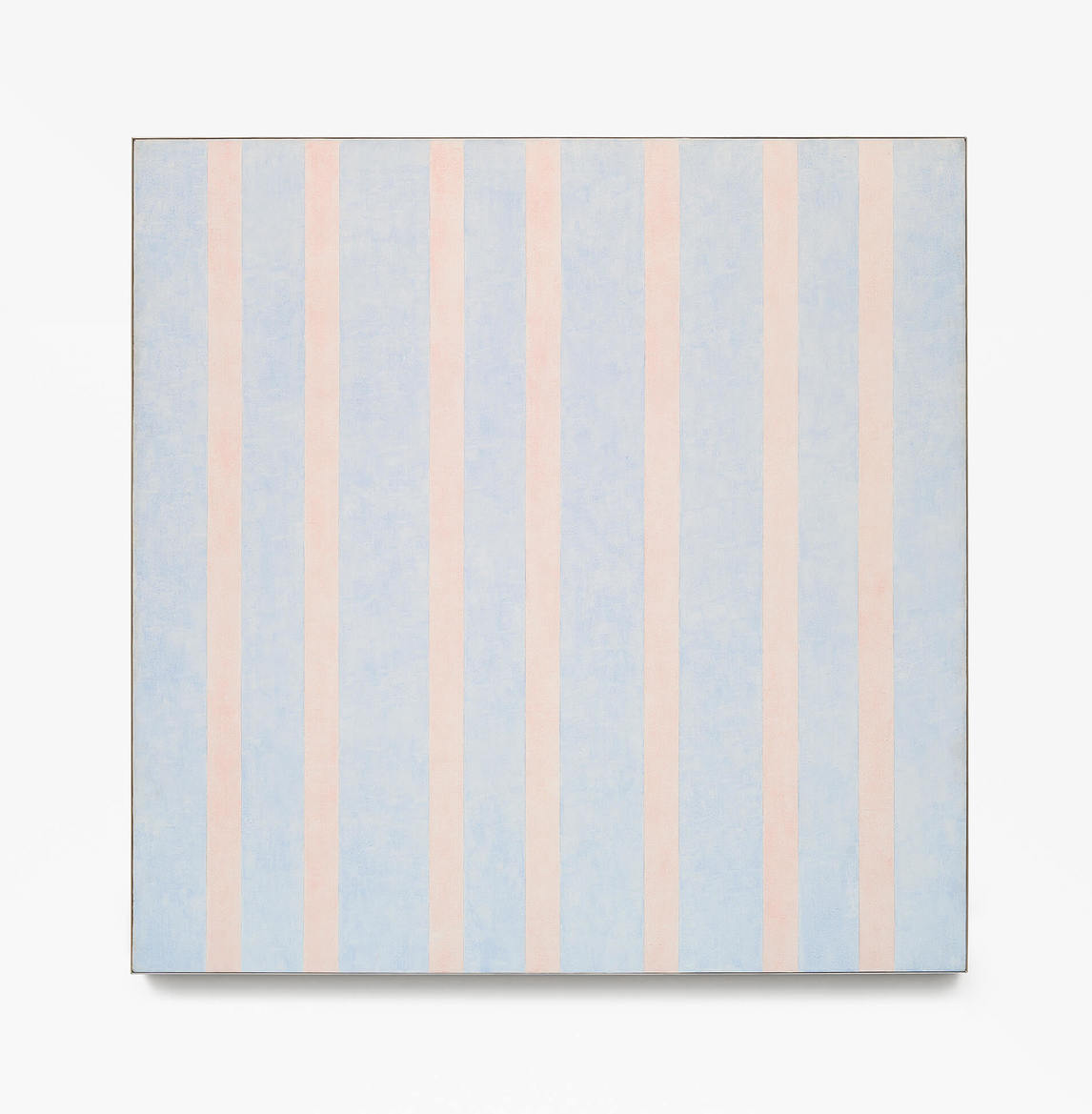

Martin sustained the general format of the grid, but in place of the horizontal and vertical pencil lines from the 1960s, she started painting wider bands of colour, usually horizontal, but occasionally vertical in orientation. In effect, Martin had moved beyond the grid while maintaining some of the grid’s formal characteristics. By the time she completed the twelve-part The Islands I–XII in 1979, Martin had ceased to paint vertical canvases. She concentrated exclusively on horizontal compositions until the 2000s.

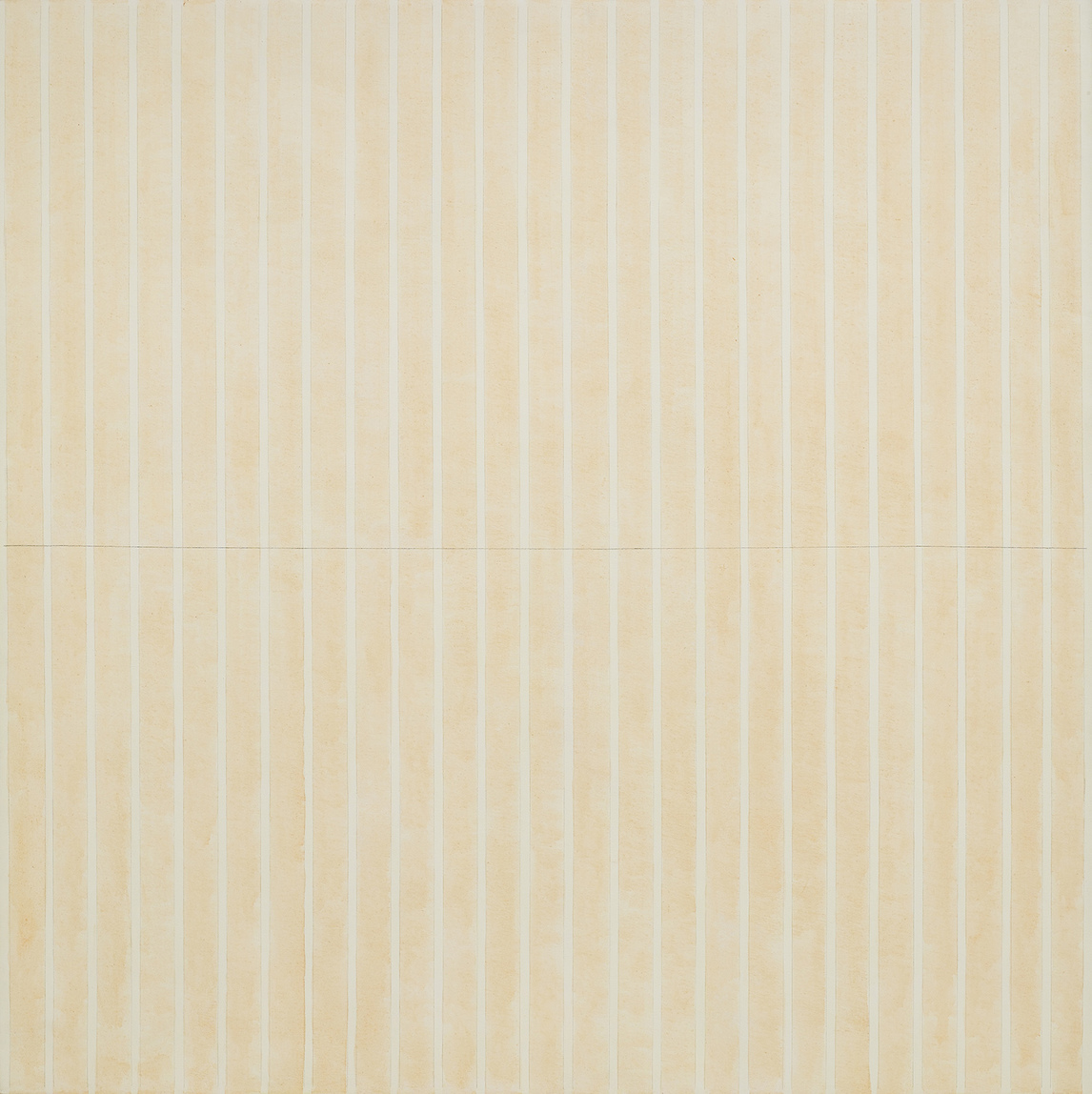

Before 1967, Martin had worked in a variety of media and investigated different materials in her painting including oil, acrylic, wood, and gold leaf. After 1974, Martin settled on acrylic gesso with graphite pencil lines for her canvas paintings. The horizontal works of the 1980s and after generally took the form of alternating bands of colour, such as Untitled #12, 1981, or a white canvas with graphite lines, such as White Flower I, 1985. Martin devised individual and complex repeating patterns for each painting to divide the canvases into distinct units. The colours in the 1970s and early 1980s were often red, blue, or orange, and thinned to evoke the sun-bleached hues of New Mexico. She used light pastel washes and embraced a wider palette than she had in New York.8

At the end of the 1980s Martin began using darker colours and made several grey paintings such as Untitled #3, 1989. After moving into a retirement home in 1992, and opening a second studio in Taos, Martin reduced the size of her canvases to five feet square and increased the frequency of her one-foot-square paintings. She found them easier to handle. Her paintings also became much brighter after her grey period, with more and more colour at the end of her life, such as in Little Child Responding to Love, 2001.

Although Martin’s painting seems to follow a gradual development from her grids in 1961 until her death in 2004, there is one conspicuous example of a major work that does not fit this structure of Martin’s artistic development: the film Gabriel, 1976. Shot on 16mm colour film using an Aeroflex camera, Gabriel is one of two films that Martin attempted, and the only one that she ever released. Although it is radically different in form from any of her paintings, its themes of happiness, innocence, and beauty are ones that Martin explored over her whole career. In this sense, Gabriel can help us develop a deeper understanding of Martin’s paintings as contemplative, requiring time and reflection, and hinting at a deep well of underlying emotion.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements