Over a long life and career, Agnes Martin intersected with and influenced many of the important art movements of the mid-twentieth century, and she is recognized as one of the most internationally significant painters of the postwar generation. Since the late 1950s, Martin has been the subject of more than one hundred solo exhibitions, as well as numerous articles and books, which offer a wide range of scholarly views on her life and art. Nevertheless, many debates surrounding the nature of her enigmatic abstract canvases, her idiosyncratic lifestyle, and her position in the history of modern art arose during her lifetime, and these continue to shape the scholarship around both Martin and her work.

Understanding Agnes Martin

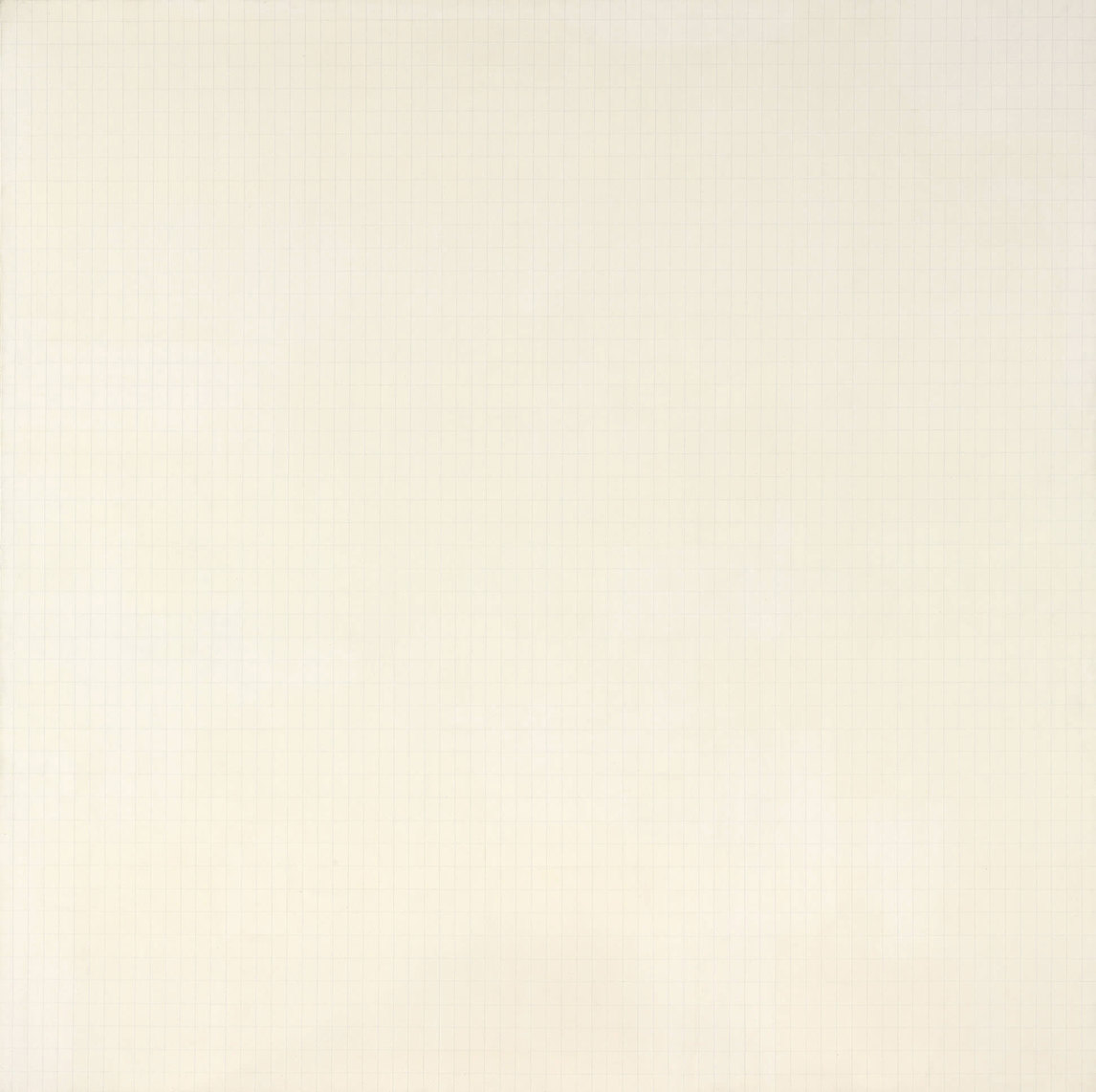

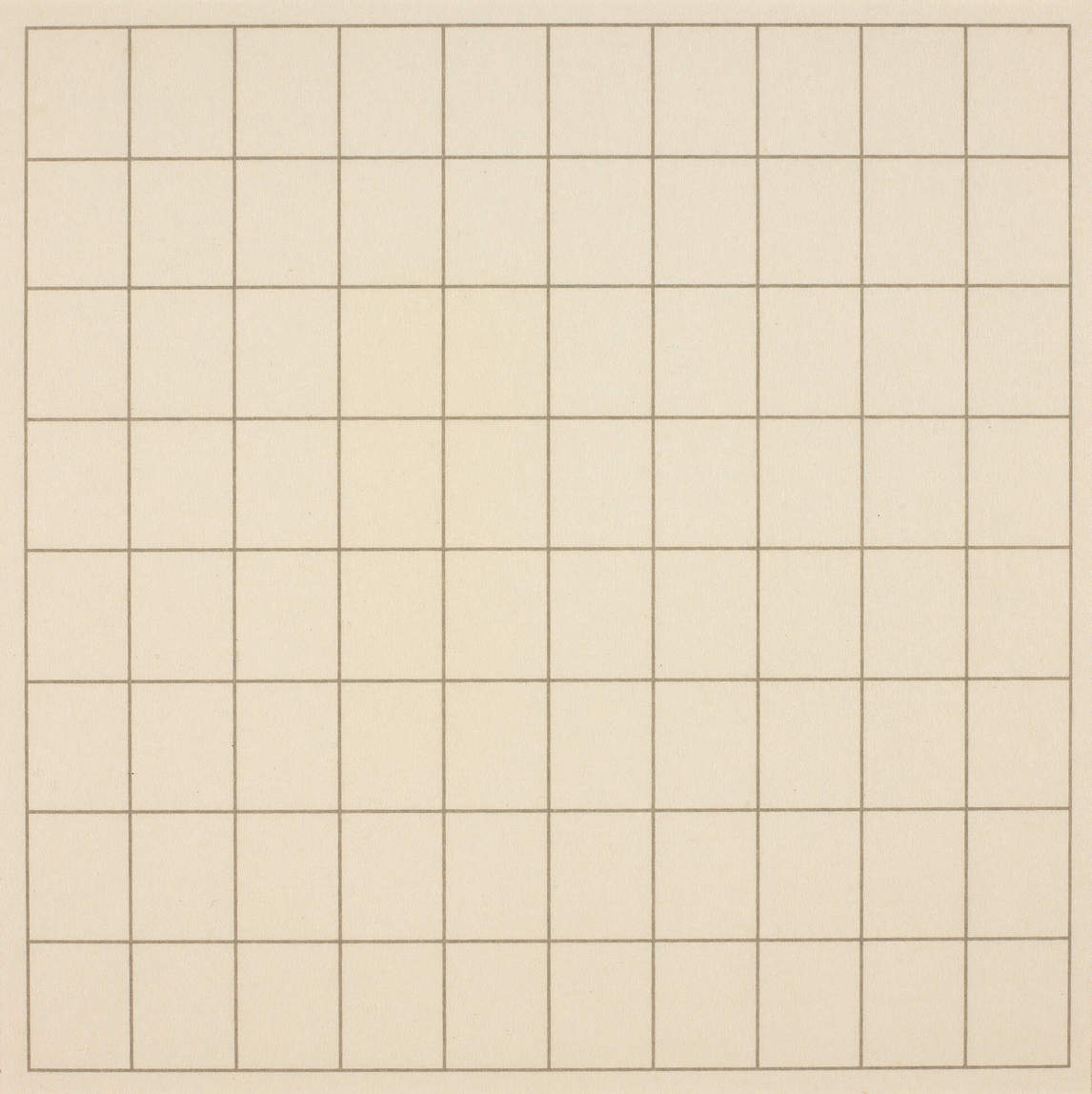

For nearly forty years, Agnes Martin was singularly dedicated to a very rigid format of painting: a square canvas or paper of consistent size and material, divided horizontally or vertically, or both, by a grid-like structure. This type of consistency is almost unparalleled in the annals of modern art. Because of this very inflexible format, it is sometimes difficult to understand what makes Martin’s paintings different from one another or to pinpoint the subtleties of how her art evolved over her lifetime using writing alone. This is one of the struggles in translating her art; it exceeds the written word.

Martin did not intend for her work to be about the formal qualities of the grid; rather, the grid was a vehicle for her to make paintings that were completely without form. She wrote, “My paintings have neither object nor space nor line nor anything – no forms. They are light, lightness, about merging, about formlessness.” Martin wished to create an abstract emotional experience; one that she likened at times to listening to music or being in the natural world. As Martin explained: “There’s nobody living who couldn’t stand all afternoon in front of a waterfall. It’s a simple experience, you become lighter and lighter in weight, you wouldn’t want anything else.”

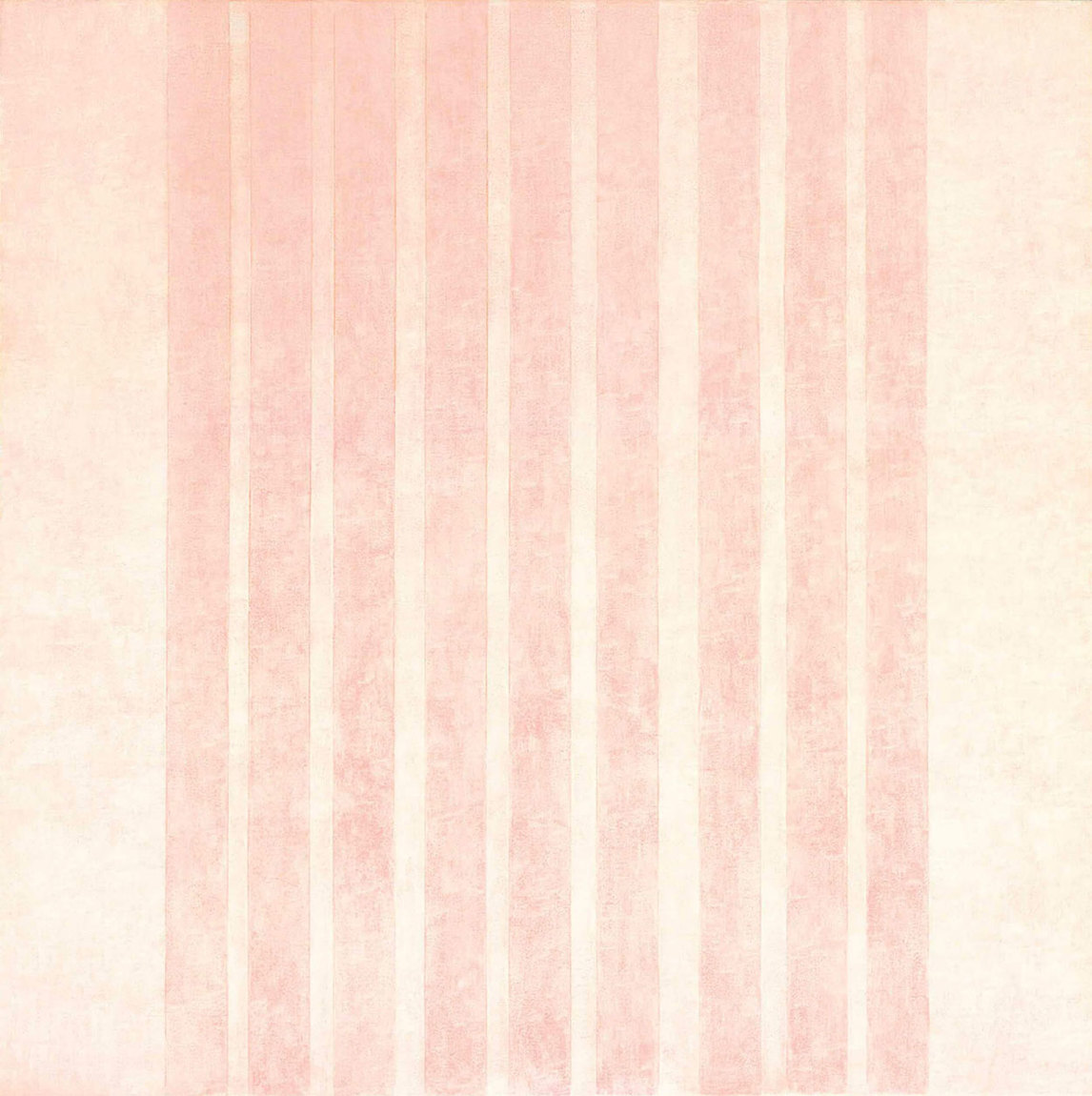

While Martin’s paintings appear to be subtle variations on a single theme, they are intended to convey a wide spectrum of human experience and emotion. According to art critic Rhea Anastas, Martin understood that her work expressed an “innate psychic realm as opposed to a formalist, rationalist sphere.” This can be seen in the description of Play, 1966, by the art critic, and Martin’s friend, Ann Wilson (b.1935). The painting is a grid of single horizontal and double vertical lines on a white background. Wilson writes that Play is “a painting about love,” arguing that “the spatial rhythm of the suggestion of infinity makes possible a state of self-loss in contemplation.”

Throughout her career Martin alternated between periods when she titled her paintings and times when all of her paintings were untitled. In the 1960s, she tended to title her works after natural objects or phenomena—for example, White Flower, 1960, The Tree, 1964, or Tundra, 1967—although they were sometimes named after actions, such as Play. These titles anchor the viewer’s experience when confronted by the painting. One can imagine standing in front of Falling Blue, 1963, and having the experience of standing in front of a waterfall as Martin described. However, she realized the limitation that the titles of her work placed on the viewer. While discussing her painting Milk River, 1963, Martin wrote: “Cows don’t give milk if they don’t have grass and water. Tremendous meaning of that is that painters can’t give anything to the observer. . . . When you have inspiration and represent inspiration, the observer makes the painting.” So it is not surprising that beginning in the early 1970s, when this statement was written, through to the end of the 1990s, Martin largely stopped giving her paintings titles. She represented her inspiration and left it to the observer to make meaning.

Martin provided guidelines on how she wanted her work to be understood in her writing and public talks. “My interest is in experience that is wordless and silent,” she wrote in 1974. “And in the fact that this experience can be expressed for me in artwork, which is also wordless and silent.” Although she wrote extensively about her own work, Martin was at times reluctant to subject her art to the critical interpretation of others. In 1980 she was offered an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which she accepted with the caveat that there would be no exhibition catalogue. This was an impossible demand to the Whitney, and her exhibition did not proceed. Titles and critical interpretation of her work were antithetical to Martin’s vision of a still and silent art. Yet in the late 1990s and into the 2000s, Martin began giving her work titles again, eschewing the natural allusions of the 1960s for very specific, emotional states such as A Little Girl’s Response to Love, 2000, and Homage to Life, 2003. These late works direct the viewer’s response more than any previous works; rather than the almost indescribable feeling of the innocence of trees, for example, Martin takes us by the hand and leads us to an outburst of love in the last years of her life.

An Elusive Modern Art

Precisely how Martin fitted into American abstraction was the subject of considerable debate during her lifetime. Martin was associated with two distinct artist scenes—first the Taos Moderns, and later the artists of New York City. The former was a group of self-described modern painters, which included Louis Ribak (1902–1979), Beatrice Mandelman (1912–1998), Clay Spohn (1898–1977), and Edward Corbett (1919–1971), who came to the remote New Mexico town from New York City and California in the 1950s. Taos had been a destination for artists since the 1890s and was well-known through the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) and the photographs of Ansel Adams (1902–1984). Taos Moderns was not an official group, but its members were inspired by Abstract Expressionism and were connected to the larger movement of postwar American abstraction: California painter Richard Diebenkorn (1922–1993) showed several times in Taos, and Mark Rothko (1903–1970), Ad Reinhardt (1913–1967), and Clyfford Still (1904–1980) all visited from New York. Reinhardt is the common figure between Martin’s world in Taos in the 1950s and her life in New York in the 1960s. The two met in Taos in 1951, and they later shared a gallerist in Betty Parsons (1900–1982). During this period, Martin painted in an abstract, biomorphic style, as can be seen in the 1954 painting The Bluebird.

In 1957, Martin moved to New York and specifically to Coenties Slip, where a small enclave of artists had taken up residence in abandoned ship lofts on the eastern shore of Lower Manhattan in the 1950s. Like the Taos Moderns, the artists of the Slip, including Robert Indiana (1928–2018), Lenore Tawney (1907–2007), Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015), James Rosenquist (1933–2017), and Jack Youngerman (b.1926), were not unified by a single style but by a shared sensibility and geographic proximity. During this period, Martin developed her signature grid style, which can be seen in Tundra, 1967, the last painting she made before she left New York. Collectively, the artist scene represented a response to Abstract Expressionism; Martin can be understood as a transitional figure between the generation of Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) and Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) and the formalists—Minimalists, practitioners of Optical art (popularly known as Op art) and of Hard Edge—who followed.

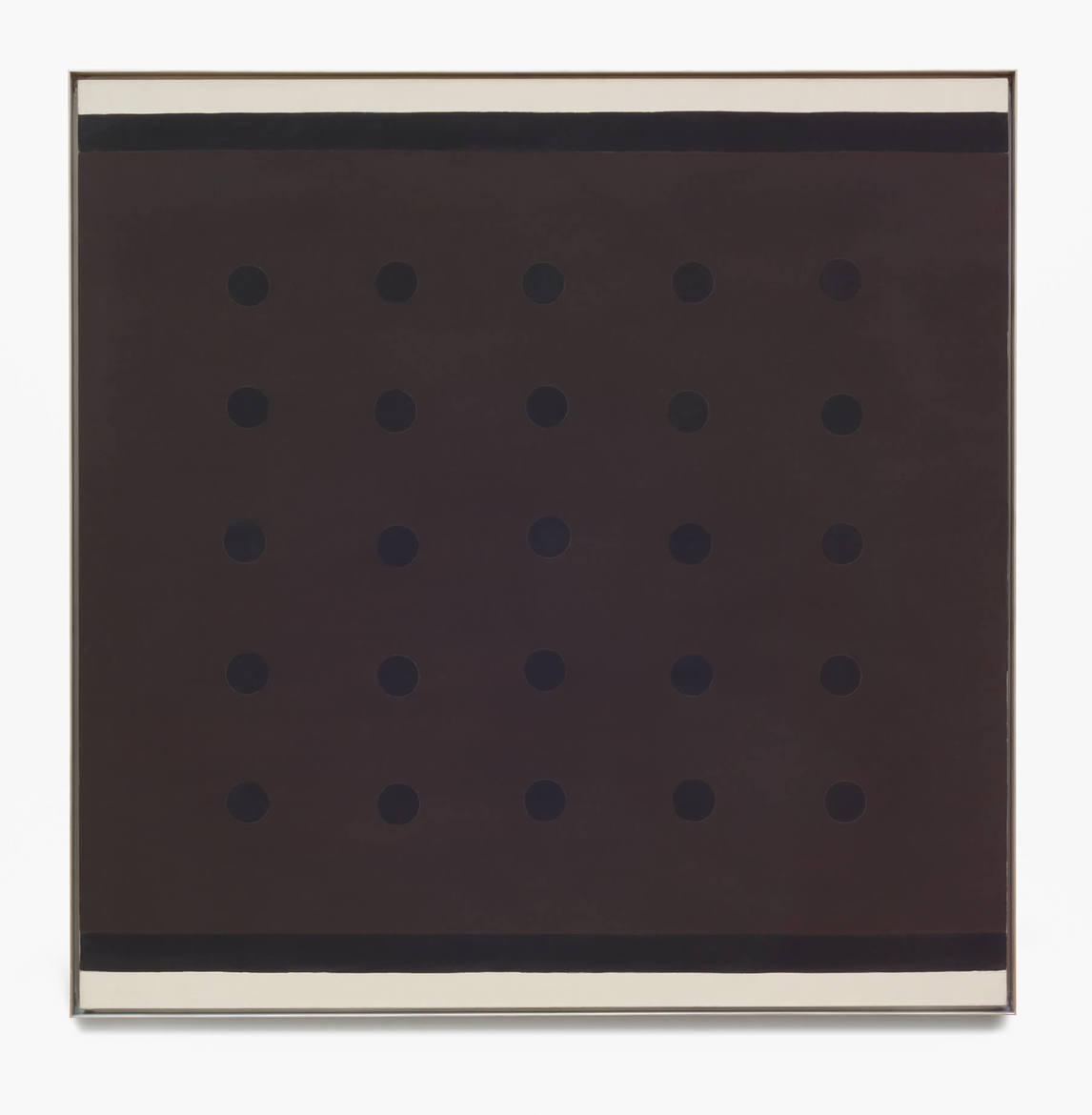

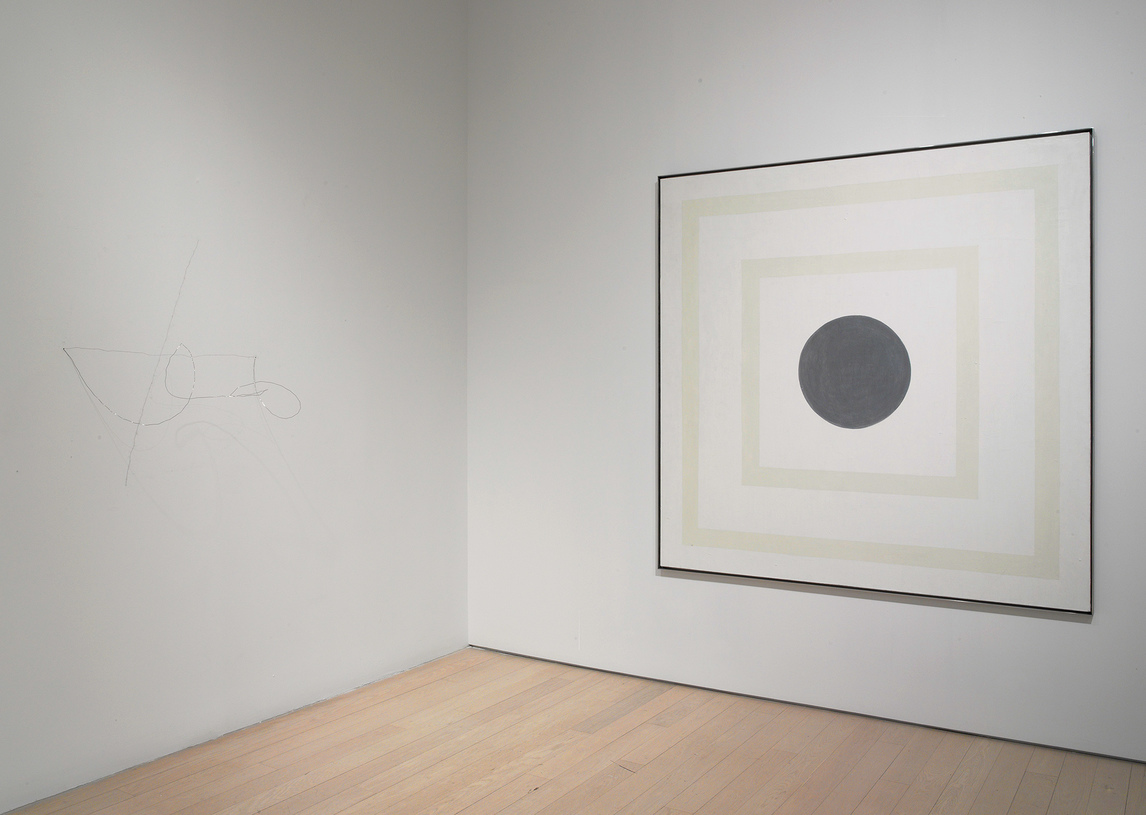

Martin was included in group exhibitions in the 1960s that placed her in the various painting camps. In 1965, the Museum of Modern Art categorized her with Op art, which was a movement of artists who explored ideas of perception through abstraction and included Bridget Riley (b.1931) and Canada’s Claude Tousignant (b.1932). While Tousignant’s L’empêcheur de Tourner en Rond, 1964, and Martin’s The Tree, 1964, were both included in the exhibition and share similar large-scale formats and make use of geometric shapes, his canvas creates a distinct sensation of movement that is not present in Martin’s canvas.

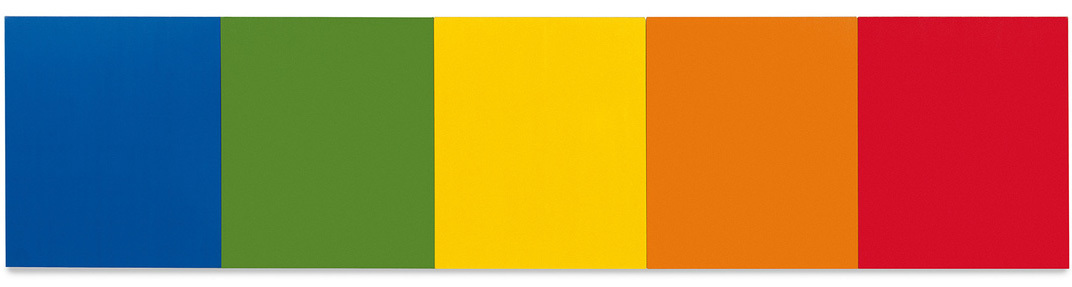

In contrast, a 1966 exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum characterized Martin’s The City, 1966, along with Ellsworth Kelly’s Blue, Green, Yellow, Orange, Red, 1966, as examples of Hard Edge painting. Curator Lawrence Alloway argued the term opposed the geometric abstraction of Op art and was “a way of stressing the wholistic [sic] properties of both the big asymmetrical shapes” of Kelly and the “symmetrical layouts” of Martin.

That same year, Martin’s Leaves, 1966, was exhibited alongside Minimalist works by Robert Morris (b.1931), Carl Andre (b.1935), and Sol LeWitt (1928–2007) at the Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles. The exhibition included monotone and grid-based paintings and sculptures that were stylistically similar to Martin’s work. Although this was a visually coherent exhibition, the artists could not agree on a statement or even a title that encapsulated their movement. Martin later stated, “They were all minimalists, and they asked me to show with them. But that was before the word was invented. . . and then when they started calling them minimalists they called me a minimalist, too.” The art critic Lucy Lippard noted that Martin’s paintings had an emotional complexity that set them apart from the minimalists, calling them “unique in their poetic approach to a strictly ordered and controlled execution.”

Martin rejected all of these associations, insisting that they ignored the underlying emotion of her grid paintings. She considered herself to be a member of the Abstract Expressionist movement, which included many immigrants to the United States, such as Willem de Kooning, Hans Hofmann (1880–1966), and Mark Rothko. However, Martin’s formative years in New York occurred after the supremacy of the movement had waned, and her self-identification with it was based on philosophical considerations more than any formal connections. Her paintings lacked the expressive gestures and drips of Pollock’s monumental canvases, for example, or the vivid merger of abstraction and representation of de Kooning’s Woman series. Yet Martin saw her paintings as part of the same emotional trajectory: she told the New Yorker that the Abstract Expressionists “dealt directly with those subtle emotions of happiness that I’m talking about.”

National Identity

Like many aspects of Agnes Martin’s life, the issue of her nationality was complex. Martin was born in Macklin, Saskatchewan, in 1912, lived briefly in Calgary, Alberta, and moved with her family to Vancouver when she was around seven years old, remaining there until she completed high school. Martin first moved to the United States in 1932, at age twenty, to help care for her sister who was ill, and she stayed because of the educational opportunities.

Martin identified as an American artist from at least the 1940s, and she became an American citizen in 1950. In a 1954 grant application to the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, Martin writes of her interest in “assisting the establishment of American Art, distinct and authentic. . . an acceptable representation of the expression of the American people.” In a letter to a friend around the same time, she writes glowingly that “almost everyone in America is creative about what he does in his way of living and this is a wonderful thing because it has always been the tendency in this culture.”

Martin’s position can be contrasted with that of other Canadian expatriate artists in the 1950s, such as Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), and Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), who had established their markets in Canada before leaving and who benefited from the support of the Canadian art establishment while abroad. Martin was never associated with any Canadian art movement; as a result, she was virtually ignored by collectors and galleries in Canada until late in her career. To this day, she is considered an American artist, even in Canada. Her painting, White Flower I, 1985, for example, hangs in the postwar American art galleries at the National Gallery of Canada, alongside works by Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, and Mark Rothko, and not in the Canadian and Indigenous art galleries. The Rose, 1964, similarly hangs in a gallery dedicated to American art at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

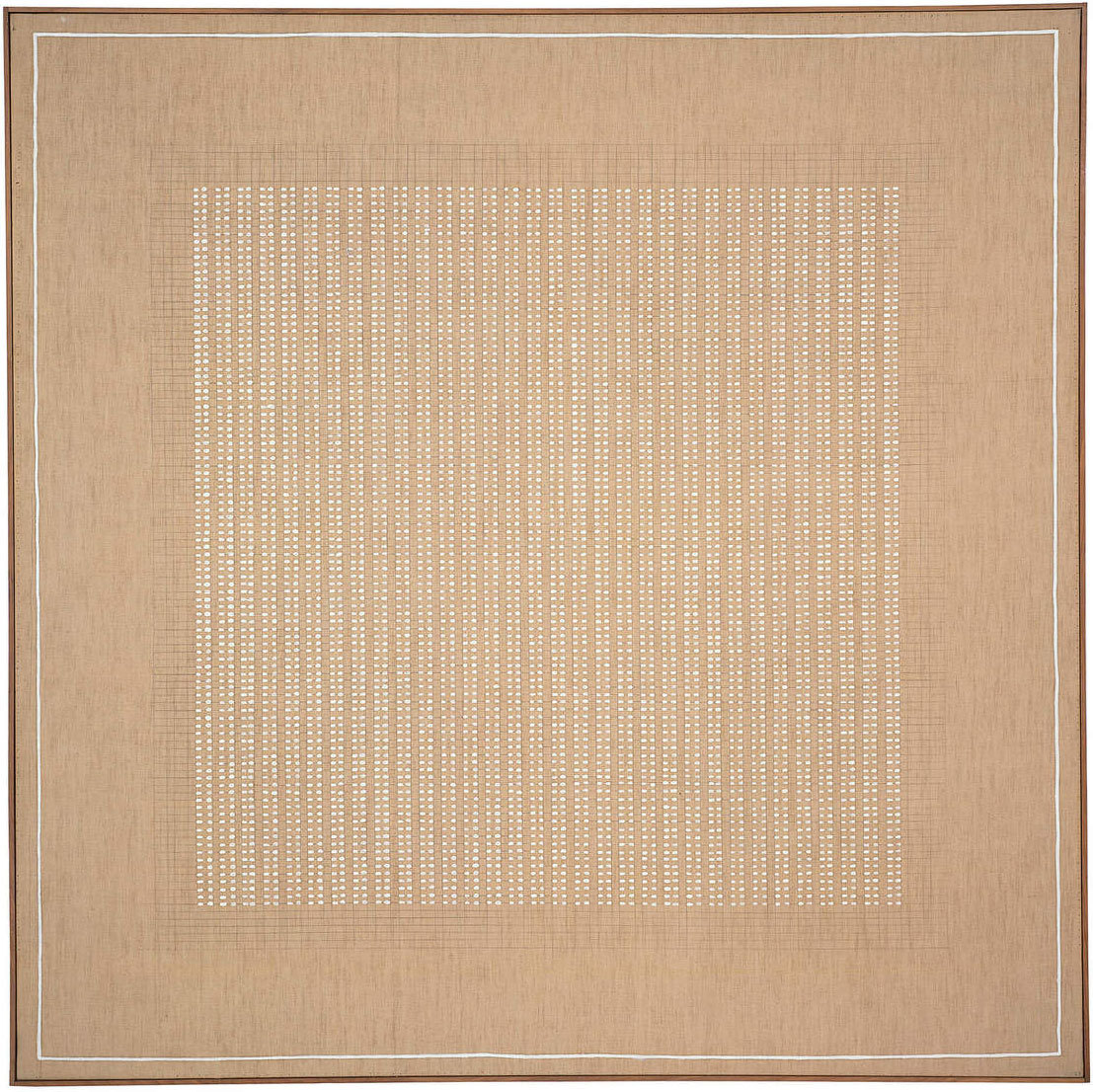

In America, ironically enough, Martin was often associated with Canada. The critic Dore Ashton made a connection between Martin’s paintings and the vastness of the Saskatchewan prairie in a review of her second exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1959: “Agnes Martin was born in Saskatchewan and brought up in Vancouver and the great prairies have lodged in her imagination ever since.” Perhaps Ashton was thinking of the painting Earth, 1959, a canvas of just over four by four feet that was included in that exhibition. The picture shows a grid of twenty-five dark brown circles on a lighter brown background, with horizon-type lines at the top and bottom, giving the impression of a very simplified farmer’s field. Critics also associated Martin with the Indigenous cultures of Canada, presumably Cree in Saskatchewan and the Nations of the Pacific Northwest in British Columbia. Ashton later recalled that when she met Martin in the late 1950s, the artist “spoke of her youth in Canada, of her exploration of the Indian [sic] culture there, and—proudly—of her work with mining and logging companies.”

The source of her unembellished canvases and austere lifestyle have similarly been attributed to her childhood in Canada. Art critic Holland Cotter singled out Martin’s Presbyterian grandfather and his perceived Calvinism as an influence: “It is surely to this childhood one must look first in considering Martin’s paintings and writings.” Although Martin told Ashton, “I guess I am really an American painter” in 1959, similar tropes drawn from her Canadian heritage to those outlined above persisted in American writing on her work throughout her career. Martin herself may have encouraged these comparisons to the Saskatchewan prairies, at least passively. “My work is non-objective,” she maintained, before adding, “but I want people, when they look at my paintings, to have the same feelings they experience when they look at landscape so I never protest when they say my work is like landscape.” Take, for example, Grey Geese Descending, 1985. The title evokes a flock of geese touching down, perhaps on a snow-covered farmer’s field, as suggested by the grey-white canvas and horizontal lines. Yet for Martin this is an attempt to represent the feeling of the grey geese descending and not a physical component of the scene based on observation.

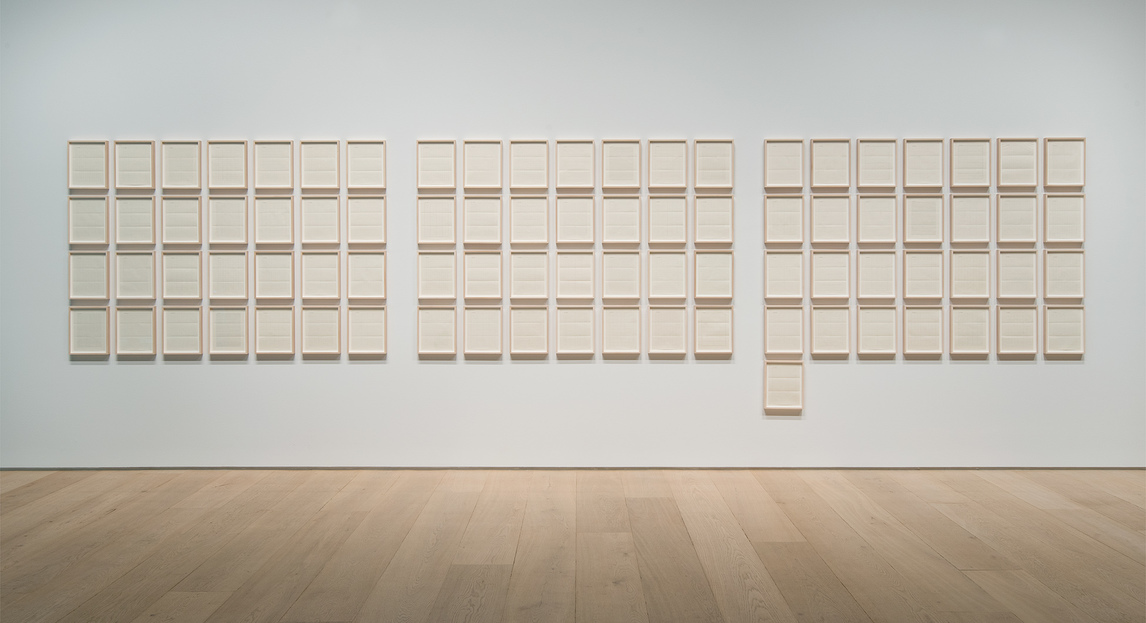

Despite living in the United States for over seventy years, Martin did maintain a lifelong connection to Canada. She spent time with her family in British Columbia intermittently during the decades after she left, and also made more wide-ranging visits, including in Canada’s centennial year of 1967, and again in 1977 to work on a film in Victoria, British Columbia. Canadian museums and galleries started recognizing her work in the 1970s, first with purchases of Untitled #8, 1977, and The Rose, 1964, by the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1977 and 1979 respectively. In 1985, the National Gallery of Canada purchased White Flower I, 1985. Since that time the prices for her canvases have steadily risen, and no other Canadian museum owns a painting by Agnes Martin. Despite this, Martin’s influence on contemporary Canadian art can be seen today, particularly in the work of Saskatoon-based artist Tammi Campbell (b.1974). Her ongoing piece Dear Agnes, begun in 2010, consists of a grid drawing she composes each day based on Martin’s On a Clear Day, 1973. Campbell has completed over one thousand of these drawings to date.

With Her Back to the World

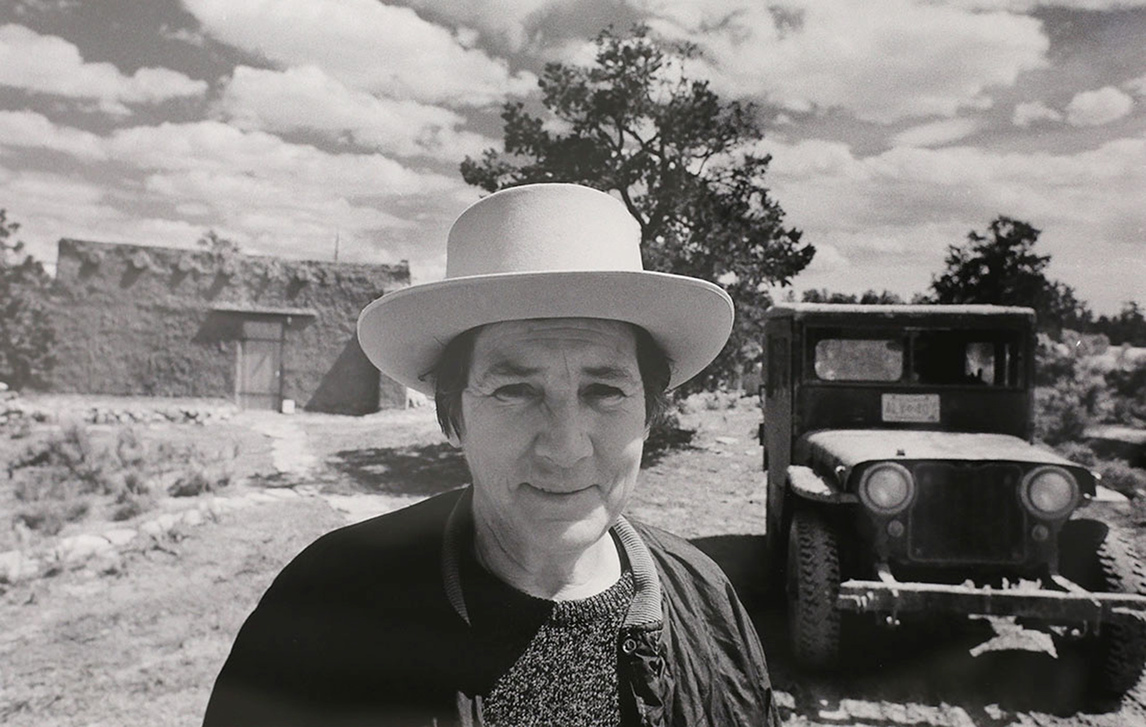

Following Martin’s dramatic departure from New York in 1967, she spent a year and a half travelling North America. She found her way to Mesa Portales near Cuba, New Mexico, in late 1968; the six years that followed were ones of self-imposed solitude, during which Martin did not paint. She would return to it in 1974.

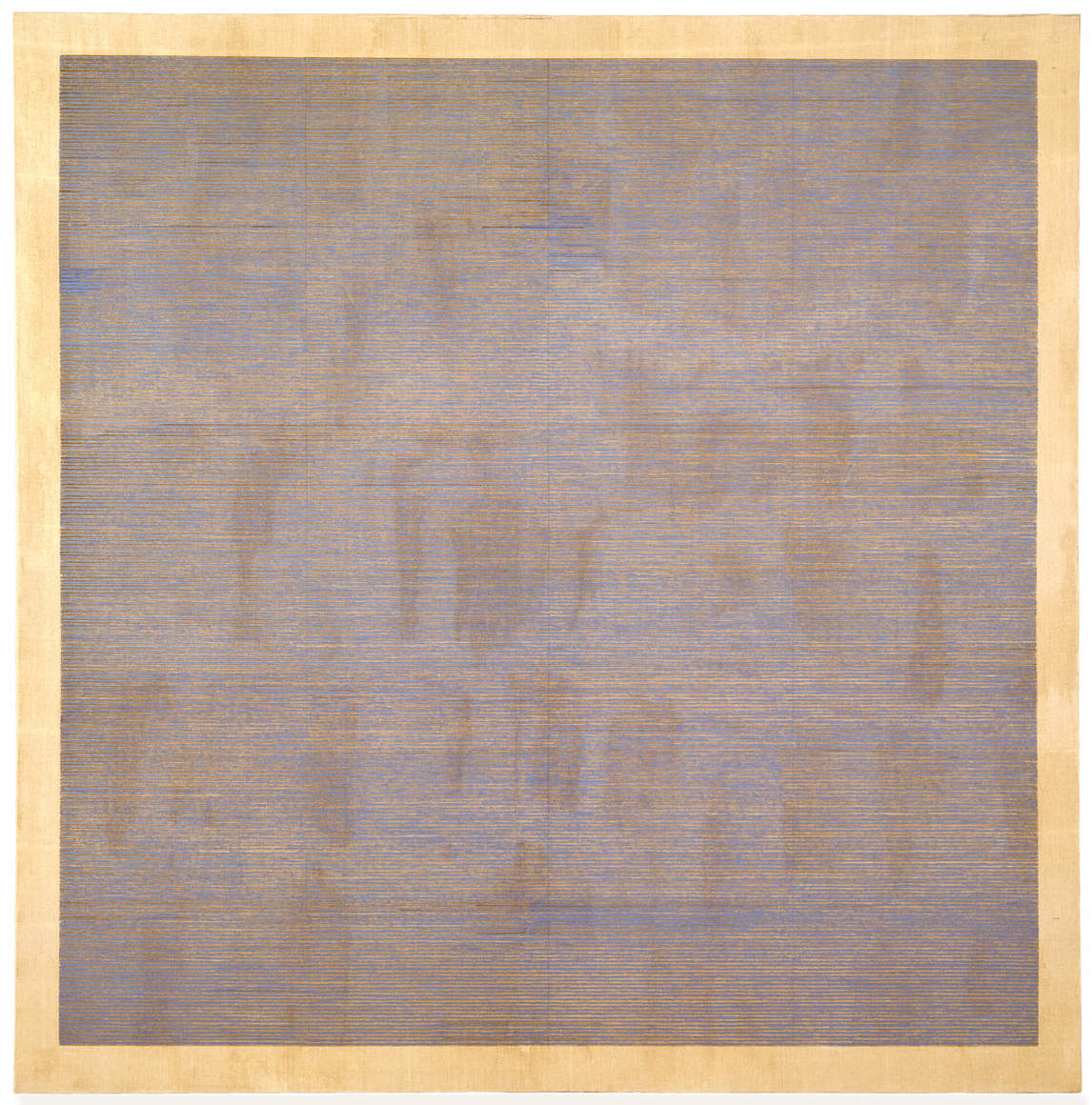

Although Martin had lived most of her adult life in precarious and nomadic circumstances, press accounts began to focus on this dimension of her life more after her move to Mesa Portales. At the same time as she was introducing new colours and redefining her grid style in paintings such as Untitled #3, 1974, a new conversation began developing around Martin as a person in the early 1970s. An ascetic public persona began to emerge, with Martin herself helping to construct the image through interviews in the popular and art press, as well as her own extensive writing.

Martin’s new self-positioning can be traced to two texts that appeared in 1973, around the same time as her first retrospective exhibition held at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. The first, “The Untroubled Mind,” appeared in the catalogue for that exhibition. The text consists of quotes by Martin, transcribed by Ann Wilson, in which the artist argues for the importance of innocence and beauty in art. To Martin, the untroubled mind is found in early childhood and is a moment when “inspiration is most possible.” Undoubtedly inspired by her attraction to Eastern philosophy, Martin notes that the artist must proceed without ego. “It would be an endless battle if it were all up to ego,” she wrote. “Because [the untroubled mind] does not destroy and is not destroyed by itself.” Martin’s own Tao-inspired writings have inspired Taoist interpretations of her paintings, such as by the art critic Thomas McEvilley, who likens her grid paintings to the “uncarved block” or a state of potential being. “Activated and tingling, the grid is the place of infinite creativity,” he writes, concluding with Martin’s own words: “the ground to which we must return for ‘the renewal of memories of moments of perfection.’”

The second text, “Reflections,” was transcribed by Lizzie Borden for Artforum from an interview with Martin and explores what she calls “the perfection underlying life.” Martin observes that a work of art is “successful when there is a hint of perfection present” and calls the act of seeking perfection “living the inner life.” Not all artists live the inner life, Martin concludes, but “others,” presumably referring to herself, “live the inner experiences of the mind, a solitary way of living.” She makes very explicit connections between solitude and even privation and perfection in art: “In these moments. . . we wonder why we ever thought life was difficult.”

Beyond seeing herself as an Abstract Expressionist, Martin recognized her art as part of a “classic tradition” that included Coptic, Egyptian, Greek, and Chinese art. She connected these traditions of art-making with her own paintings and considered the art object to be a representation of ideals held within the mind. It is within this context of classicism that Martin’s grid paintings must be understood: “I was thinking about innocence, and then I saw it in my mind—that grid. And so I thought, well, I’m supposed to paint what I see in my mind. So I painted it, and sure enough, it was innocent.” When she painted what she saw in her mind, this connected her to the traditions of the past. “Classicists,” she wrote, “are people that look out with their back to the world.” This notion inspired Martin for most of her adult life. Although she first wrote the statement in 1973, Martin revived the sentiment in a six-panel painting from 1997, With My Back to the World. In this series of blue, yellow, and orange striped paintings, one can understand the connection that Martin believed existed between abstraction and emotion. “Not personal emotion,” she would say, but “abstract emotion. It’s about those subtle moments of happiness we all experience.” Martin believed that the object of painting was to “represent concretely our most subtle emotions.”

Critical and Commercial Significance

Agnes Martin is one of the most critically and commercially successful abstract painters of the second half of the twentieth century, achieving a high level of sustained, global recognition since the 1970s. She has been the subject of several major touring retrospectives over the last forty-five years, the first organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania in 1973 and another soon after in 1977, organized by the Arts Council of Great Britain. The 1990s saw back-to-back retrospectives for Martin, first at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1991, and then in 1992 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Most recently, the Tate Modern in London organized a posthumous retrospective that travelled to the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York between 2015 and 2017.

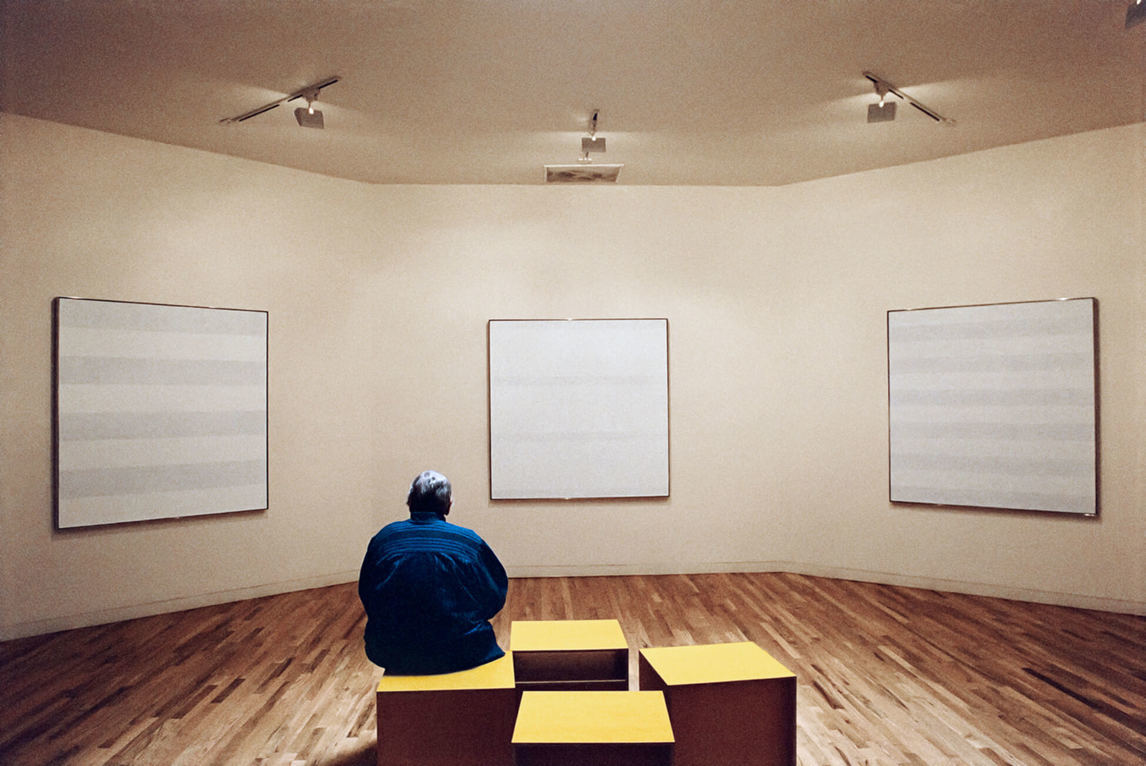

Martin’s work commands high prices—Orange Grove, 1965, set a record in 2016 with a sale price of US$10.7 million, making it one of the most expensive paintings by a Canadian-born artist ever sold at auction—and it has been widely collected both privately and by institutions around the world: in New York, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Guggenheim all have extensive collections of Martin’s work, as do the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. The Dia:Beacon in New York, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, and the Harwood Museum in Santa Fe all have permanent and multi-artwork displays of Martin’s paintings. The Harwood Museum’s Agnes Martin Gallery attracts visitors from all over the world.

Martin has had an influence on subsequent generations of artists, including Richard Tuttle (b.1941). Tuttle, who also lives in New Mexico, has been described as a Post-Minimalist. The two artists exhibited together, including at SITE Santa Fe in 1998. Martin also had a tremendous influence on younger female artists such as Eva Hesse (1936–1970), whose too-short career in New York almost matched Martin’s own time in the city, and Ellen Gallagher (b.1965). Thanks in part to the influence of her work on subsequent generations of female artists, Martin has gained a reputation as a feminist icon. Her friendship with feminist writer Jill Johnson, her success as a female artist in a male-dominated era, her sexuality, and her ambiguity around gender all feed into this narrative. Martin herself refused this label, telling the New Yorker bluntly: “The women’s movement failed.” She did not identify as a feminist and would deride those who would describe her as such.

In 1997, Martin was awarded the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the Venice Biennale. This event set off a series of awards and accolades that included both the United States’ National Medal of Arts in 1998 and Canada’s Royal Academy of the Arts Award in 2004. During the last years of her life, Martin was the subject of a documentary, With My Back To The World, which offers an intimate portrait of the artist at a time when she was arguably at her most philosophical. “If you wake up in the morning and you feel very happy about nothing, no cause, that’s what I paint about—the subtle emotions that we feel without cause in this world,” Martin says of her works. “And I’m hoping that people, when they respond to them, will realize that. . . their lives are broader than they think.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements