Contemporary, Toronto-based artist Shary Boyle discusses how Christiane Pflug’s Cottingham School with Black Flag, 1971 was a seminal inspiration for her as a student. Boyle reveals her fascination with Pflug’s unique, intense, graphic artworks and how they made her feel that becoming an artist was possible.

You’re listening to Under the Influence a series of podcasts featuring contemporary Canadian artists talking about the art legends who have influenced their own work. Today I’m speaking with Toronto-based artist Shary Boyle about the influence of Christane Pflug’s work.

SH: Shary what images come to mind when you think of Christiane Pflug’s art?

SB: I guess I think a lot about landscape—urban/suburban landscape—in a Canadian sense. I think of the early small little sketches she made when she was kind of free and young in Paris and Tunisia, which were more landscape, kind of countryside, images. And then later on the classic domestic space with children perhaps in or out of the picture.

SH: Can you describe her approach to drawing and painting?

00:01:00

SB: When you look at her work you can really see that she was a keen observer and she had a ton of focus in her subject. It’s so interesting to me what she chose to draw, which was exactly what she saw, but that you can see how much she was trying to learn through that observation. And you can see that focused intent in her line. I feel like her work was very— pressed very hard in the paper. I think that [a] hallmark in her pictures is how hard and dark the graphite—say of her drawings—[was] and you can feel the intensity of her physical presence on the page. Literally, you can kind of turn the page on an angle and see where the light hits the graphite. And there’s like a three-dimensional quality, because she’s dug so hard with like her entire muscle into paper to the point where you’re almost waiting for it to rip open.

Description of Artwork

SH: The act of looking [is] something that she learnt over time, and as a self-taught artist looking was a big part of understanding art, and she didn’t really have an influence per se, but was really interested in all areas of art. Could you speak to the idea of being self-taught?

SB: She didn’t go to art school, she wasn’t trained, yet, she had a partner at an early age that was trained and had a lot of strong opinions about art making and the practice of creating and technical kind of approaches. So it seemed like there was a strong influence of his ideas about how art should be made. Perhaps she didn’t choose to make images from her imagination. She chose to try to replicate what she saw in front of her, so in that way too, I see that she was technically just trying to advance and learn and push forward her skills. And you see those skills develop over her relatively short career, which was very serious. And I think sometimes when we think of untrained artists, we think of folk artists. But in her work as a kind of untrained artist she’s actually incredibly skilled, and she has a wonderful sense of perspective. She’s really interested in architectural space, so she’s making hydro lines and these tall-rise buildings and windows and kind of suburban or urban space that’s very believable that has a depth to it that you can see what’s in the background what’s in the foreground. All of these without the training of any kind of device or strategy, she’s just really observing and trying again and again and again. There’s something to be said, obviously, that she’s not out in the field, especially as towards the later part of her life, she’s looking through a lot of windows. She doesn’t like to move, and, when they did move house, they chose their apartment or their houses in Toronto, depending on what the view was out the window, so she could have a good space to paint from, to look out. So there is a sense that she was inside looking out.

00:04:00

SH: Do you remember the first time you were struck by Pflug’s work.

SB: The first work that I encountered, and why it struck me, was the Black Flag painting and the black flag of course was a really subversive image of this, kind of a downtown, like maybe just outside of downtown Toronto, street. It’s looking out a window, you’re looking in the background, you’re seeing some high-rises and some hydro poles and then a lot of horizontal electrical wires that are kind of bisecting the sky and the middle ground; you had this wild forest, and, I feel, like the way she does vegetation can sometimes be kind of alive. And then there’s this really wild wavy green mass of summer foliage behind a very typical kind of row housing in Toronto, right across the street, from where she is living. And just to the left of centre is this Canadian flag, but it’s painted in black and white.

The black flag of course was subversive to me in the early 90s, but also because the first thing I thought of was this California hardcore band from the 70s and 80s called Black Flag. And I was pretty into their music in high school, so it was just like an immediate symbol of this subversive anti-authority kind of sticking it to the man image that seemed really shocking and incredible in this, in this kind of hyper-controlled—almost, you know, a real strong attempt to have a realism in the work. But with this one image that seems so out of context, in something that seemed almost precious in its intensity to detail. Right, so that contradiction was fascinating to me because it seemed really out of place but also really heartening. Like who is this?

SH: Pflug was born in Germany and moved to Toronto in 1959 with her two daughters. And upon arrival it was a bit difficult getting that artistic spirit up-and-running, and she had stated that she had to learn here, and that she initially found the surroundings banal or ugly. But slowly she saw it differently. You have worked in several places across Canada. How do your surroundings affect your work as an artist?

SB: I think that there’s, you know, there’s geography of the land and nature and then there’s a geography of the social and the urban and those are two such different principles of influence. So if you’re going to go to Berlin or you’re going to go to Helsinki or you’re going to go in some like, you know, city—Bangkok, some place where there’s rich cultural traditions and a lot of people—then it’s going to be the people and their stories and the buildings that they’ve surround themselves with that are going to cause some kind of … you know, you’re going to get really excited and inspired and you’re going to want to respond in some way or it’s going to sometimes [be that] those situations hone and clarify who you are in response to them. So that might give you some new insight about your own perspective and what you really care about by feeling so foreign.

Then there’s the other thing of just nature and landscape and geography. So you can be up in the Arctic or you can be in some desert and be profoundly moved by something that’s so much more powerful than you that you might, you know, take your work in some different direction, and you do see that in her earlier work. I would say that she was painting and drawing what she saw and all of a sudden the children come in and a few really stilted images of people are self-portraits and then these endless images out the window, which can’t help but make you sense her stillness; so much she seemed to be just rooted to the ground inside of a room, looking out [of] a square frame, and I feel like I have a hunch or a familiarity in her intensity of line and mark and how carefully she is studying and looking, and to me a lot of the works that she did in pencil when she got to Toronto really kind of remind me of a lot of works that I did in my early 20s. That sense of really, really careful observation and connecting what you’re seeing or thinking about with a line speaks to me so much of interior space and the kind of solitude that one brings to really careful art making that takes a long time to create. And to me it feels so much the intensity of her, in her world, whether she’s channeling it through these observations and this really careful studious making. I almost feel like she is doing an external thing through her internal self; it’s very private yet public work. It’s a strange tension I find in her work and that makes me feel sad.

00:09:03

SH: There is a common thread in a lot of the work that she’s produced while she was in Toronto the appearance of birds and planes. Hearing your perspective now really changes how you would perceive those as kind of an escape route or so wait and like return back to Tunisia or Paris or something like that. Is there visual tropes that you like to use in your work.

SB: It’s interesting. Symbols are metaphors in artwork, right. And when you see her kites or her birds or her planes you do see that kind of—it’s hard not to read that as an escape; but symbols are metaphors that are recurring in my own work. I have returned to the spider web many times, many different installations or iterations in drawing or painting. I find that as a metaphor, [it’s] really open ended and compelling to me because it’s—I’m trying to work out a life experience, which, for me, my work is very much connected with the experience of being human and that’s an emotional and a physical and an intellectual thing in relationship with, you know, mortality and illness and other people that I love or [have] conflict [with]. So the web ends up being this amazing device to kind of speak about narratives that [an] individual might craft, that are the connections to other people, and the webs of relationships. But there’s also the idea of kind of trapping yourself: Self-entrapment. I’m really interested in the habits of mind that we develop over a lifetime—that we work so hard to unravel that we get stuck in and that we, you know, find ourselves doing the same thing over and over again whether we realize it or not. Some of those are either activities or characteristics or ways of thinking [that] could have started out as a healthy thing, a coping strategy, and then over time they get so rigid and calcified. You can escape, you know, but at the same time we weave webs or stories about ourselves that are attractive and seductive and can be a way that we draw people closer or things that we desire closer. I’m interested in the push pull between the contradiction of creativity, and, maybe, the chaos of that creativity, when it’s not quite going right.

00:11:18

SH: Georgiana Uhliarik at the AGO is working on a kind of career-spanning retrospective of Pflug’s work. Why do you think it’s important to be looking at Pflug?

SB: No, I think it is important to be looking at Pflug at any time. You know, I think that art does go in and out of fashion and that there’s certain styles or mediums that people are more interested in at any given time in the contemporary art world. It’s a pretty fast moving trajectory of what’s of interest to the general—that general kind of audience. It’s so important to have any kind of skills. A compelling, interesting, deep, complicated female artist that has you know created their work in Canada to be actively available studied and understood, known, seen as a role model or a mentor or some one that kind of makes anybody feel less lonely, especially for young women artists. Anybody should be able to look at any work and really try to use it to gain empathy for that person’s perspective why they’re making it. But I think her work in particular is so personal, it’s so human. It just speaks to a general audience outside of the kind of contemporary concerns that could be so helpful for people to get to know their place and to feel a sense of history in the city, but especially for young artists. And when you see some skilled artist that also is a woman, you feel an entry point of possibility, and I think that for me discovering this woman’s work when I was young, and kind of identifying with those really tight graphic lines and the kind of intensity that she brought to it, made me feel that it was possible.

SH: That was Shary Boyle speaking with us from Toronto. Shary has exhibited and performed nationally and internationally and represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. Under the Influence is a production of the Art Canada Institute an organization with a mission to make Canadian art history a contemporary conversation. The show is produced by Ashley Walters. And I’m your host Stefan Hancherow. Thanks for listening.

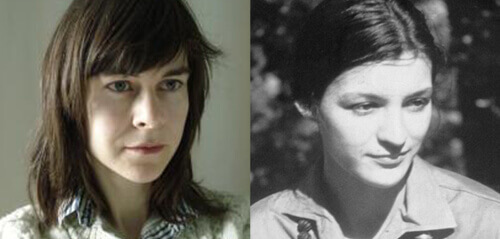

Shary Boyle

on the influence of

Christiane Pflug

Shary Boyle

on the influence of

Christiane Pflug