Screenwriter, playwright, award-winning novelist, advertising executive, artist. Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) may be one of the most interesting figures in Canadian art, not least for his success in a variety of fields. In the wonderful new online book by James King, Bertram Brooker: Life & Work, Brooker comes across as a true Renaissance man, defined as much by the various careers that fed his art, as by the art itself.

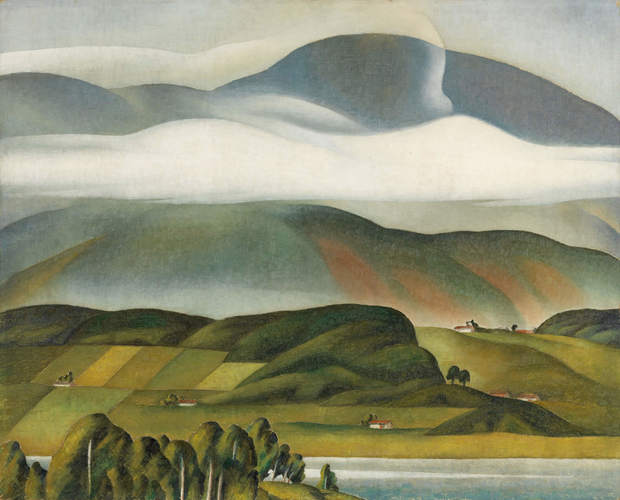

Oil on canvas, 61.3 x 76.2 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Born in London, England, Brooker came to Canada as a child and by his early twenties, he was living in Portage La Prairie, a small town 80 km west of Winnipeg. Around this time, he travelled to London and New York City to “catch up with drama and literature and art happening”. There is no record of what he saw, but he was likely exposed to Post-Impressionism and Vorticism, along with works by Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp and Alfred Stieglitz. In 1912, Brooker and his brother, Cecil, moved to Neepawa, Manitoba, where they opened a movie theatre. In one of the funnier episodes in the book, King describes Brooker complaining to Vitagraph Studios about their awful films. With the film production company politely replying that he should write his own scripts, which Brooker would do and create several which were successfully turned into films.

By including anecdotes such as this, King uses the narrative style he so successfully applied in his biography of Greg Curnoe to once again excel in bringing his subject to life. Brooker comes across as a man with a sturdy moral compass, a drive for success and a strong work ethic, as well as some insecurities. He particularly disliked the suggestion that he was overly influenced by the work of others, once saying of the 1934 Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition in New York that “some of which [the works] looked awfully like my early abstract things, and I didn’t like them, perhaps for that very reason”.

By 1913 Brooker was married and by 1921 he was living in Toronto, where he worked as an illustrator and advertising executive by day, while painting in the evenings. For much of the 1920s, Brooker supplemented his advertising income with prolific freelance writing. The years 1922 to 1924 saw an increased focus on painting. His work from this period suggests an artist still finding his way. Through exposure to the work of other artists – including a somewhat fraught friendship with Lawren S. Harris with whom he shared an interest in spiritualism, and a more collegial relationship with Lionel LeMoine-FitzGerald – Brooker worked his way between abstraction and a more representational modernism, continually refining his artistic vision.

Oil on canvas, 43 x 61 cm, Museum London

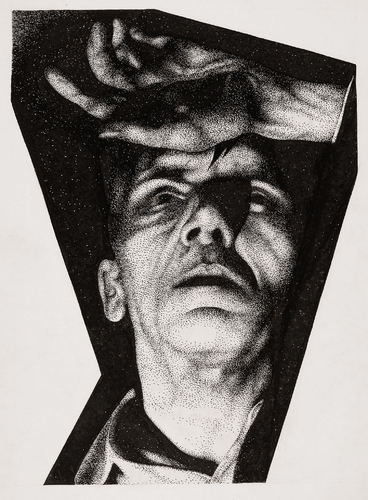

King comprehensively explores the artist’s many avenues of artistic expression, his interests and influences such as music. Particularly striking are examples of Brooker’s black-and-white illustration work which often features eerie closeups, dramatic lighting and odd angles, perhaps affected by his earlier career operating a movie theatre. Equally arresting are examples of Brooker’s nudes, which have the unblinking joli laid style more commonly associated with contemporaries like Stanley Spencer and which were highly controversial in their day.

Pen, brush, and black ink over graphite on illustration board, 38.2 x 27.8 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Throughout his life, Brooker taught himself to see differently. He was not only one of Canada’s earliest abstract artists but also part of an avant-garde movement that included such luminaries as Vassily Kandinsky. Complex, clever and slightly infuriating, Brooker may not be as well-known as the artists with whom he rubbed shoulders, but much of his work has held its appeal to this day, suggesting a man who was actually ahead of his time.

Although Brooker was himself an author and critic, his art and career have rarely been explored in print to any significant degree. James King, in this publication by the Art Canada Institute, has elegantly filled that gap, in a book that balances entertaining biography with a carefully considered critique of Brooker’s work, style and technique. The result is a valuable addition to the discourse surrounding Canadian modernism and its influences, as well as a highly entertaining read.

Read the article as originally published here.

Read the online art book here.